‘A Lovely Back…’ – Provenance Research at the Deutsches Historisches Museum

In July, a major campaign gets underway at the Deutsches Historisches Museum: documenting the reverse sides of paintings in the permanent exhibition. Around 220 paintings were already examined in the museum storerooms at the start of the year, but now it is the turn of paintings actually on show. Dr. Heike Krokowski, provenance researcher at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, describes the laborious steps involved: the individual pieces of a big jigsaw-puzzle must be found and fitted together, so that, finally, the past history of an object can be revealed.

Since November 2017, the Deutsches Historisches Museum has been checking to see whether any of the objects in one section of its paintings collection were acquired as a result of Nazi persecution. As well as examining museum and object files, running database searches, and carrying out documentary research, this systematic audit involves surveying and documenting the versos of paintings. For the back of an oil painting can hold vital clues to its whereabouts at a particular time and even the identity of previous owners.

Examining and documenting the reverse side of a painting. © DHM

Around 480 pictures are being researched for potential evidence of expropriation during the Nazi era as part of a project financed by the Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste (German Lost Art Foundation) in Magdeburg. Some 250 of them are currently on display in the permanent exhibition, and these are being examined during the month of July; meanwhile the exhibition remains open to visitors as normal. Part of the upper floor of the Zeughaus has been cordoned off to create a temporary ‘workshop’; here the paintings are photographed, and any clues found are documented.

The temporary ‘workshop’ in the permanent exhibition on the upper floor of the Zeughaus. © DHM

These clues might include labels or inscriptions from earlier exhibitions, sales, or previous owners. If they appear potentially significant, follow-up research is carried out. In the case of an exhibition label, checks are made to discover when and where the exhibition took place and whether a previous owner is mentioned in the exhibition catalogue. Signatures and stamps must be deciphered, and former owners or art dealers written to. Surveying the backs of paintings and the follow-up research do not always result in solid evidence, but every little piece of information is part of the puzzle and can be fitted into the larger overall picture of the chain of ownership.

The reverse side of a painting with its labels and inscriptions. © DHM

In the public gaze

A picture-hanging team transports each painting to the temporary ‘workshop’, where it is placed on an easel. It is then minutely examined with a magnifying glass under good lighting and the details are recorded and photographed. A written record is made of every mark, including any faded inscriptions, torn stickers and physical alterations to the canvas or the frame. The smallest detail might turn out to be a crucial piece of the puzzle, helping to solve one of the numerous questions surrounding the provenance of an artwork.

Taking down a large-format painting for the investigation of the reverse side. © DHM

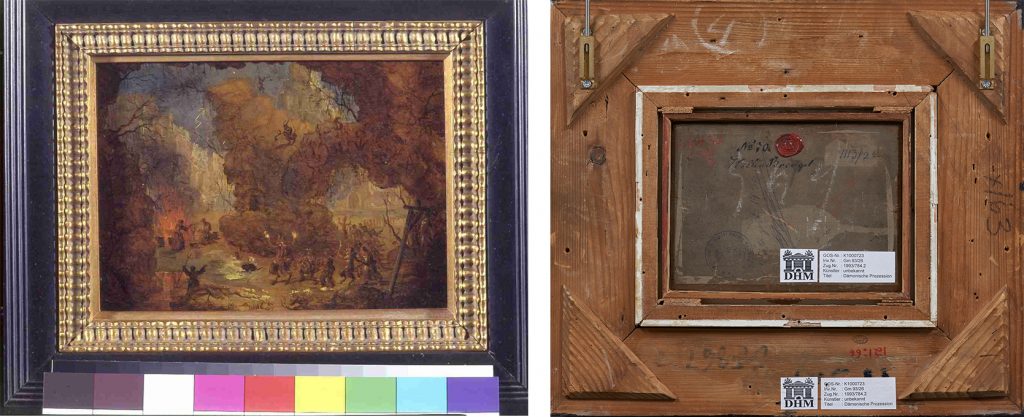

A similar documentation campaign was already carried out at the start of 2018 in the storeroom at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, with the marks on the backs of more than 220 paintings being examined. One of the artworks analysed and photographed was Dämonische Prozession (Demonic Procession), by an anonymous 17th century Dutch artist. Painted on wood, it had numerous ‘provenance marks’ on the reverse: several inscriptions, presumably giving information about the artist, old inventory numbers and dates, a collection stamp made of sealing wax, and a number of sales marks. Moreover, the picture also bore the stamp of an Italian historic monuments authority, authorising the removal of the painting from Italy, and a further stamp, consisting simply of a few capital letters: ‘CAM ST. LOUIS’. Both this stamp and one of the inscriptions, reading ‘121 : 66’, could be attributed to the City Art Museum of St. Louis in the United States.

Dämonische Prozession (Demonic Procession), flemish, ca. 1650. Front and reverse side of the painting with all its inscriptions and stickers. © DHM

The Saint Louis Art Museum, as the institution is known today, responded to our enquiry by confirming that it had purchased the painting in 1966 and disposed of it again some twenty years later when it had been pruning its collection. In March 1987 it had sold the painting at Christie’s in New York. This explained how the work came to be in the Deutsches Historisches Museum even though it bore the inventory stamp of a North American museum.

All the other provenance marks on the painting Dämonische Prozession are still waiting to be deciphered, however. We are particularly keen to find out whether the numerous inscriptions can give any information as to the whereabouts of the painting between 1933 and 1945, because the ultimate goal of this most unusual campaign in the permanent exhibition of the Deutsches Historisches Museum is to clarify the provenance of these almost 480 paintings.