7 Questions for Antje Liebers

On Reconstructing the Frankfurt Kitchen from our Arts and Crafts Collection

Miriam Barnitz | 4. September 2019

The Frankfurt Kitchen and its architect, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, who greatly influenced the Neues Bauen (New Building) movement – particularly in Frankfurt – loom large in this Bauhaus centenary year and the current bauhausweek berlin. Her revolutionary, innovative design is also a key feature in our exhibition “Weimar: The Essence and Value of Democracy”. After an intensive, complex restoration and partial reconstruction, our Frankfurt Kitchen, a part of the collection since 1992, can now be presented to the public in its entirety, as one of the few remaining originals from the period. Antje Liebers, who has been the museum’s in-house wood conservator for 30 years, oversaw the project. She sat down with our trainee Miriam Barnitz to talk about why she won’t forget restoring the Frankfurt Kitchen anytime soon.

Mrs. Liebers, restoring an entire kitchen sounds like a complicated task. How did you react when you first heard about the proposal?

Antje Liebers: I’ve been familiar with our Frankfurt Kitchen since the mid-90s, and I knew right away, boy, we’ve got our work cut out there! Because it had never been presented in its entirety, the kitchen was still a collection of individual pieces. Important elements were missing. And it had been restored only partially – and rather unprofessionally at that. But this kind of project is often a godsend for collection objects, because they are made fit for exhibition for the long term. We inspect them with a fine-tooth comb. Time is never on your side, though, when it comes to preparing and performing conservation treatments. You have to ask yourself, what’s the most economical and fastest way – that entails the least red tape – to prepare an object for exhibition and preserve it for the future? If you want something done quickly and economically, it’s best to do it in-house, where we have many respected experts in our team. We had to work together in researching the objects’ history and coming up with solutions, especially when reconstructing the colour palette – something that kept our collection manager, Dr. Leonore Koschnik, and I very busy!

So the process required a lot of team work. Who was involved and how?

We have many specialists working at the museum, both in the conservation department and the workshops. Our team consists of carpenters, painters, metalworkers, and others – all of whom are highly professional and bring many years of experience to the table. And so I thought it could only be beneficial to draw from this diverse pool of experience and take on the project together. Because we continually rotate our exhibitions, the museum staff is always on a tight deadline, and we had very little time at our disposal to prepare this exhibition. Needless to say, I was thrilled when my colleagues Torsten Ketteniss and Kai-Evert Kriege from the wood workshop, Gunnar Wilhelm from the painting workshop, and Jens Albert from the metal department agreed to take it on. They were all keen to join me on this unusual project, and brought their own innovative approaches from day one. We visited other museums that also have Frankfurt Kitchens, including the Bröhan-Museum and the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge. We examined them up close, took photographs and measurements. We all made our own observations, and that’s how, step by step, we developed a plan to conserve and reconstruct our Frankfurt Kitchen. It quickly grew into a labour of love. We were eager to finally see the completed kitchen in the exhibition, and were also excited to see our colleagues’ reactions.

A large part of your work involved reconstructing the missing pieces of the Frankfurt Kitchen. What makes them so special, and how did you go about replacing them?

Generally speaking, every Frankfurt Kitchen is different. Ours came from the Römerstadt estate in Frankfurt, which was built in the late 1920s and designed by urban planner Ernst May. These small kitchens were laid out according to guidelines specific to each street of the development. This information about the object’s provenance was a place to start. By researching and analysing the various Frankfurt Kitchens – our own and those from other museums – and a few publications on the topic, I was able to visualize the kitchen’s original lay out.

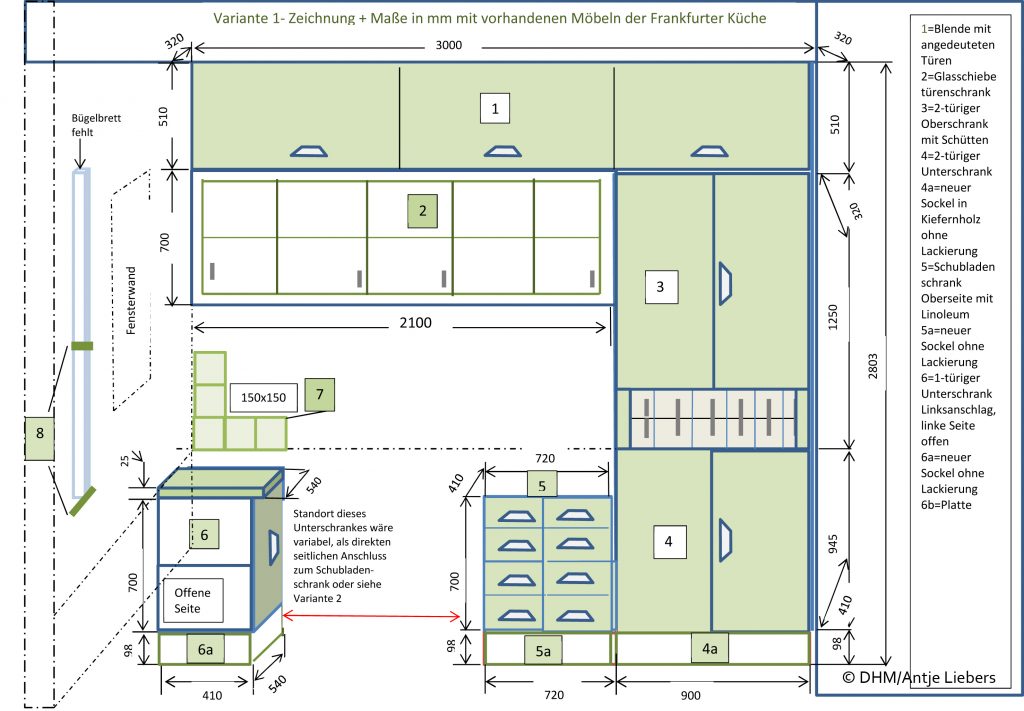

Graphic digital drawing of the existing elements of the Frankfurt Kitchen © Antje Liebers / DHM.

I completed sketches of different potential configurations for our exhibition, based on contemporaneous floor plans. These first drawings helped me to understand what exactly was missing. For example, next to the cabinet with drawers in our collection there should have been a double sink, which back then would have been available in various materials, such as porcelain, ceramic, and stainless steel. And it was so important to add in details, like the draining rack, the ironing board, and the work surface in front of the window, above the waste drawer. These innovations demonstrated how little things can simplify routine procedures.

In the end, aside from reconstructing the colour, there weren’t too many missing pieces – everything was there. Our two carpenters, completely detail-obsessed, went about making the missing objects from scratch. In addition to getting the dimensions right, the choice of material was critical. What did the elements look like back then? What materials did they use, how were they crafted, with what kind of finish? Ultimately, these reconstructions, with all their attention to detail, naturally had to blend into the kitchen – but at the same time, we wanted them to be transparent, recognizable to visitors for what they are: replicas. That was the tough part.

Among other places, you spent time at the Bröhan Museum and the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge. What was it like to work with these institutions?

The other museums were wonderful to work with. You can’t just assume you’ll be granted access to objects on display – or that you’ll be allowed to get your tape measure out and start measuring them during visiting hours. But after I explained our intentions, they gave us free rein. Director Tobias Hoffmann and his colleague Sonja Jastram at the Bröhan Museum welcomed us and answered a few questions. He also put me in touch with a collector who knows the ins and outs of the Frankfurt Kitchen. That was invaluable. We were able to talk in-depth and he even offered to search for original replacement parts for our object. The timeframe was a bit too tight for that – but I really appreciated his offer!

Before its restoration, the Frankfurt Kitchen at the Deutsches Historisches Museum looked very different – especially its colour. How did you reach this decision?

In 1997 individual elements from our kitchen were reworked for the first time. External contractors tried to repaint the kitchen in a new colour. Unfortunately, all the old paint layers were removed in the process. Seen from today’s perspective, that decision can only be described as sub-optimal, especially because they slapped a quick coat of acrylic in ‘bottle green’ on every surface. The original paint was oil-based. That makes a huge difference when it comes to the look of the choice of colour. In order to visualize the difference, Gunnar Wilhelm made special test boards with various paint samples. Leonore Koschnik and I quickly agreed that we had to replicate the original as closely as possible.

The Frankfurt kitchen after acrylic color version 1997 © DHM.

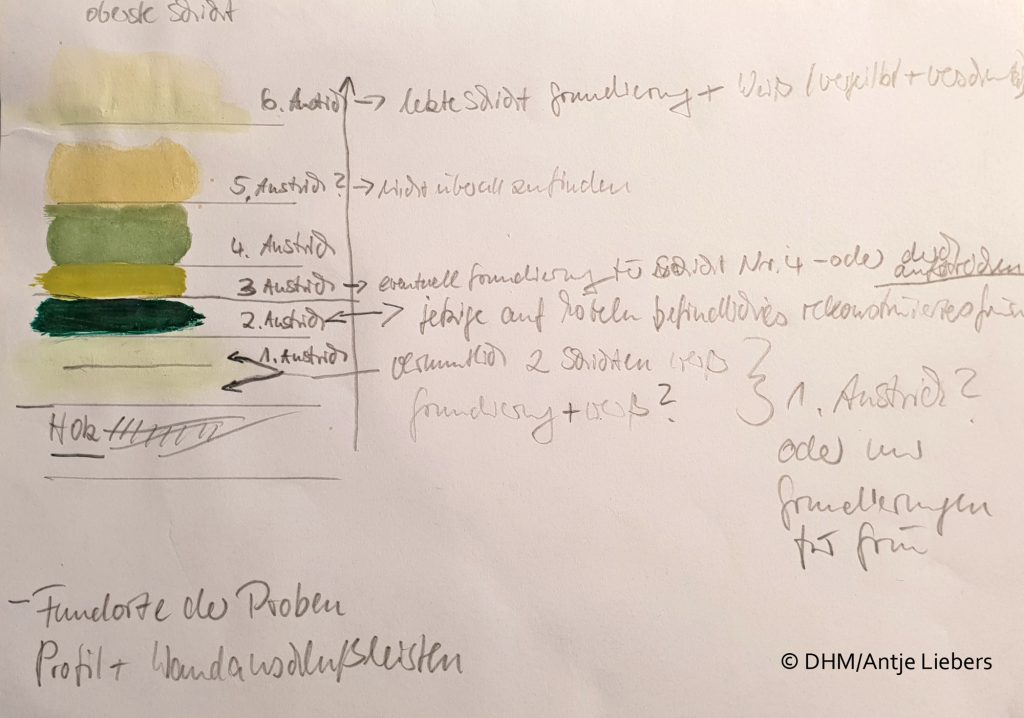

In our storerooms I also came across an old piece of the cabinet moulding, which still had traces of the original paint. I examined the structure of the paint layers under the microscope and observed a total of six paint layers, which I recorded in a kind of cross-section diagram. Now, you can’t reach a conclusion for the whole based on a single piece of moulding, but one of the lowest layers had a blue-green tone. Our collection supervisor was familiar with the Frankfurt Kitchen that’s currently at the ernst-may-haus. It has a similar blue-green tone. But we didn’t stop there. Naturally, we wanted to determine the exact colour of our object. We looked into other museums’ Frankfurt Kitchens, whose original colours, somewhere between ivory and cream, were either still recognisable or had been partially uncovered.

Color layer sketch © Antje Liebers / DHM.

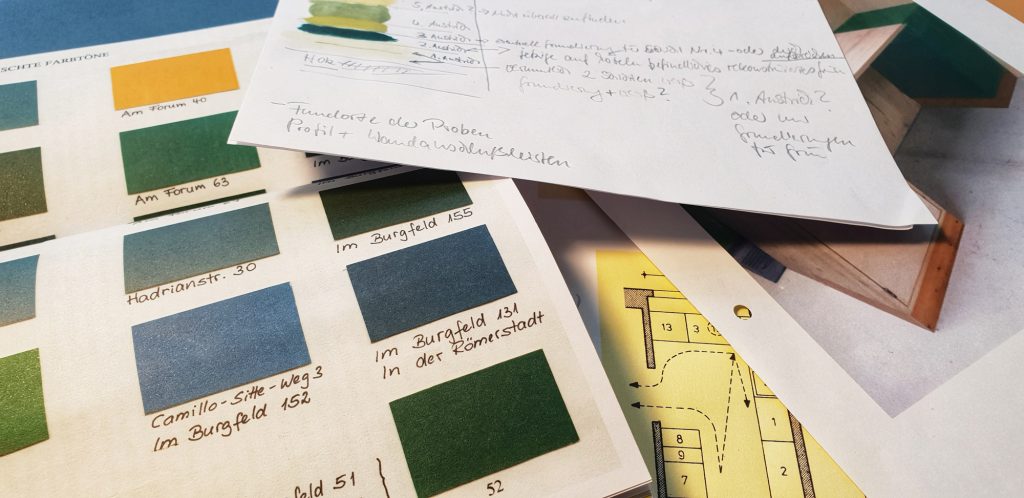

But the real game-changer was at the Werkbundarchiv, where we came across a small brochure: ‘The Frankfurt Kitchen: A Manual for Museums’.[1] It contained an ‘overview of colour samples reproduced from original Frankfurt Kitchens found in the Römerstadt estate’,[2] from the archive of the Stuttgarter Gesellschaft für Kunst und Denkmalpflege. Among them was the Hadrianstrasse model kitchen – our kitchen! After further research and a few important realizations – for example that each street in the development was assigned a different colour – and after paging through various colour catalogues, we were able to determine the exact colour code. It was RAL colour 6004 (blue-green). The RAL [abbreviation for the National Committee for Delivery Terms and Quality Assurance – Reichs-Ausschuß für Lieferbedingungen] was formed in 1925, in order to regulate and systemize the production of industrial goods. Since 1927, RAL Farben has made standardized paint shades, which they assign straightforward names, numbers, and mixing ratios. Their system guarantees that the paint tones are produced with utmost precision, up to this day. As I already said, beneath the many paint layers on the old piece of moulding we found a similar blue-green colour. Determining the colour code meant that the paint could be reproduced using an appropriate oil binder – the same one that was originally used – so that the colour spectrum was in tune with what would have been produced around 1927 or 1929. The team was naturally thrilled! And Gunnar finally knew what paint to work with. He had the difficult task of applying the new oil-based paint above the existing layers of acrylic, in a way that would allow the structure and surface feel of the wooden base below and the traces of the old finish to remain visible. His meticulousness and professional expertise created the outstanding results you see today. But it’s also been great to watch how people react to the colour. It has almost universal appeal and is absolutely timeless. I’m sure the designers were perfectly aware of how well this colour would age!

Research material by Antje Liebers. With “Summary sheet with mixed-in color samples according to original findings at Frankfurt Kitchens of the settlement Römerstadt, SGKD archive”. In: Flagmeier, Renate / Werkbundarchiv (ed.): Die Frankfurter Küche. Eine museale Gebrauchsanweisung, Berlin 2012, p. 68f. © DHM.

What are you guaranteed to remember about this project in years to come?

I’ll never forget the intense, fantastic teamwork. It was very special. Right from the start everyone was ready to give their all for the Frankfurt Kitchen – which was great. So many things came together almost at the drop of a hat: we solved problems as a team, made discoveries, found spare parts, lovingly produced new elements, met interesting people, discussed everything endlessly and, step by step, reached this astonishing result. I couldn’t have done it without my colleagues. I am extremely proud of them! So it was all the more rewarding to feel appreciated by the curatorial team and management. Our hard work was acknowledged throughout the museum. That was remarkable!

The completely reconstructed Frankfurt Kitchen in the exhibition “Weimar: On the Essence and Value of Democracy” © DHM/David von Becker.

And now we’re all anxious to see what will come next! What are you currently working on?

In addition to current loan requests, I’m preparing our next exhibition, The Crossbow – Terror and Beauty, which opens on 20 September. These elaborately crafted objects, some of them more than 600 years old, are part of our Militaria Collection. I have been overseeing their restoration for some time now. Since we’re also publishing a catalogue for the exhibition, some of the heavy weapons had to undergo conservation treatment in advance, so they could be photographed without suffering from the light exposure and be suitable for future display. Many other weapons, made from different materials, such as wood, bone, and mother-of-pearl, are still awaiting treatment. Conservators are tasked with reaching an end result that’s appropriate for each object. They have to preserve it for the future and, where conservation is necessary, take care that its patina remains unscathed and its aura as a historical artefact isn’t erased. But it’s precisely these challenges, and coming into contact with so many fascinating objects – from the crossbow to the Frankfurt Kitchen – that make my job so exciting!

References

[1] Die Frankfurter Küche. Eine museale Gebrauchsanweisung, eds. Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge Berlin and Renate Flagmeier, Berlin 2012.

[2] Ibid., p. 86f.