Leipzig ’89 – Revolution reloaded

Interview

25 February 2022

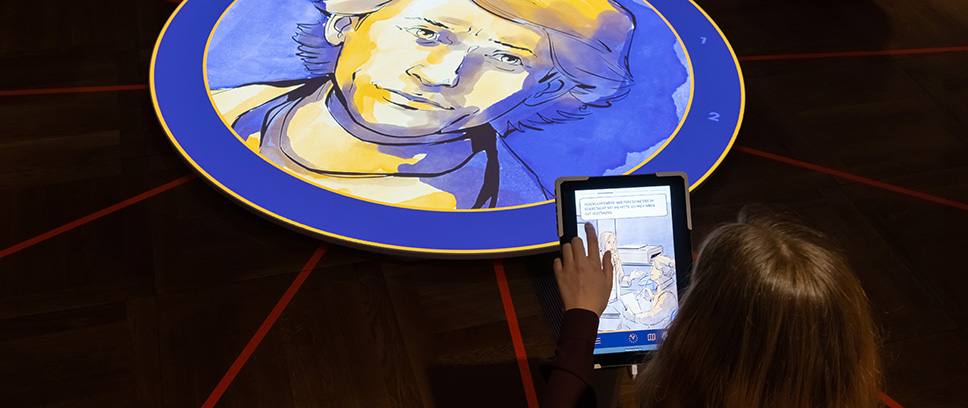

Until 27 March 2022, visitors can test the prototype of the game station “Leipzig ’89 – Revolution reloaded” free of charge in the Deutsches Historisches Museum. The digital app has been under development since early 2021 within the framework of the cooperative project museum4punkto. DHM project head Elisabeth Breitkopf-Bruckschen and game producer Martin Thiele-Schwez from Playing History tell about the project in the interview.

History communication and game design – How do they go together?

Elisabeth Breitkopf-Bruckschen: Digital games with historical storylines have been popular for a long time. From our viewpoint, playful access offers exciting possibilities to make complex historical relationships more substantial. Digital interaction can foster a lasting examination of history. Digitalisation is becoming more and more important for museums and for the communication of history. We do not believe that analogue and digital are mutually exclusive, but rather see an opportunity for the one to augment the other. In effect, we have developed a prototype with the means of game design that broadens the accessibility of historical processes. The central thought is that the course of history is the result of concrete decisions and actions, but also in part of accidents. For us it is important to research the content on a solid scholarly basis. This is the point of departure and reference for our work. It is equally important for us to link the digital space to concrete objects in the collection: the analogue witnesses of history, so to speak.

Why is 9 October 1989 in Leipzig the most appropriate date for the game? When the game was being developed, did you think of choosing another historical point in time?

Elisabeth Breitkopf-Bruckschen: On 9 October 1989, 70,000 people took to the streets of Leipzig and protested against the authoritarian state. For the first time the authorities let the people pass and did not intervene, which was by no means foreseeable. In the form of an interactive graphic novel the users of our application can experience the historical momentousness of this day and make concrete decisions with which they can more or less influence the course of events in Leipzig. By focusing on the events in the GDR in the fall of 1989, which are well-known beyond the borders of Germany and politically still highly relevant today, we want to address a broad spectrum of the public and build a bridge between past and present. Compared to other historical topics, this event is easily accessible, because we know from experience that our visitors are already well-acquainted with the subject.

Before our team decided to use the Peaceful Revolution of 1989, we considered the idea of dealing with the 20 July 1944 assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler. In the end this was discarded on grounds of its content. Other distinctive events of history such as the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 were discussed, but in the end the Peaceful Revolution of 1989 seemed the most suitable.

What roles do the users of the interactive graphic novel play in the game?

Elisabeth Breitkopf-Bruckschen: There is a selection of seven partly fictitious, partly real persons, including the conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Kurt Masur, and the then General Secretary of the SED, Egon Krenz. For each player character, so-called collective biographies and individual daily routines with decision-making situations were developed on the basis of historical research and with the aid of contemporary witness reports. It is important to represent the events of the day from different viewpoints and with individual interests. The aim is to bring the different perspectives on this event to light and to show its consequences. The civil rights activist Sabine, who plays an effective role on the side of the demonstrators, naturally has a different agenda than the riot police officer Thomas, who despite his qualms defends the interests of the state power. Almut, who gets drawn rather accidently into the demonstration march while searching for her son, also sees the events from her point of view. In developing the characters it was important to design all of the positions humanely and believably. In this respect, the view “from below”, in other words the experience of the “normal population”, was particularly important, because this is often neglected in the principal writings on history.

Martin Thiele-Schwez: With “Leipzig ‘89 – Revolution reloaded” the aim was to create a multi-perspectivist narrative that uses playful means to make it possible to experience the activities of numerous actors in forming the decisive course of history. The players are repeatedly faced with decision-making situations: What flyer should the civil rights activist print, how harshly should the policeman intervene, or should Kurt Masur participate in the Appeal of the Six? These and numerous other decisions formed the events of the day and thus the course of history. In selecting the figures who can be played in the game, it was important to depict both the “normal population” and the supposedly most powerful decisionmakers such as Kurt Masur and Egon Krenz.

In realising “Leipzig ’89 – Revolution reloaded” were you faced with special challenges involved in integrating real stories into the game?

Martin Thiele-Schwez: In the playful communication of history, it is always about the question of how complex historical relationships can be broken down into relevant decisions and exciting stories. Abstraction and reduction are relevant methods in game design. Nonetheless, here in particular it is important to work closely with the historians. In the collaboration between historians and game designers there must be permanent negotiations on how the (hi)stories may be legitimately told so that they are both exciting and take account of the demands of historical factuality.

It is a particular characteristic of the game medium to allow the players as high a degree of freedom as possible. It must be possible to make effective decisions and thus to influence the flow of the story. For this very reason the game is an excellent medium for the communication of history – especially when it is about experiencing conceivable alternative courses. “Leipzig ‘89 – Revolution reloaded” has succeeded in this, because the players can experience how the variety of individual decisions have contributed to allowing the fortunate historical case of the “Peaceful Revolution” to occur.

What problems, opportunities and perspectives were gained in the collaboration between museum and game developers?

Elisabeth Breitkopf-Bruckschen: To combine elements of the game and of learning is the basic principle of serious games. This principle should be employed and a serious examination of history fostered through a playful approach. Of course, it is a special challenge for historians to represent complex historical issues in a dramaturgically concentrated way. This is why we were glad to have in Playing History a competent partner at our side.

Martin Thiele-Schwez: To transport history into a game is an exercise in translation. The spoken or, usually, the written word is transposed into multimedial and thus multi-perspectivist scenes. Suddenly history becomes experiential, playable and even alternatively changeable. Here it is extremely important that the game designers play close attention to the historical issues and deal with them very carefully. At the same time, the historians need to be willing to bring historical events into a game and to concentrate on the most gripping moments and to dramatize them scenically. It is only through continuous close communication and mutual trust that the venture of translating historical facts into a game can succeed.

The prototype is the result of a nationwide digital project called museum4punkt0. The museum4punkt0 project is funded by the Federal Commissioner for Culture and the Media after a resolution passed by the German Bundestag.