Suddenly on Point? ‘Dr Beak’ at the DHM

Life at the moment is entirely dominated by the containment measures for slowing down the spread of the novel coronavirus. Hygiene regulations, limits on social contact, ‘social’ (or physical) distancing, and – especially – face masks are now all the subject of hot debate. These kinds of measures and equipment have been deployed time and again throughout history in efforts to contain disease and sickness, which is why the Deutsches Historisches Museum’s collection includes a number of masks. However, one mask in particular has recently attracted considerable attention. After the Yorkshire Museum challenged fellow curators on Twitter to show off their ‘creepiest object’ (under the hashtag #CuratorBattle), we responded by posting the ‘plague mask’ from our Permanent Exhibition. But was it really used as ‘beaky plague protection’, as we reported in a post from our ‘What’s That For?’ series in 2017? Sabine Witt, head of our ‘Everyday Life’ division, explains why there’s reason to doubt the object’s provenance and, in particular, its use as a protective mask. In an article co-authored with Stefan Bresky, head of Education and Communication, she recently wrote about this object in the second issue of the DHM’s Historische Urteilskraft magazine. In light of the current situation, we’re sharing a slightly abridged version of the article exclusively on the DHM Blog.

A mask shaped like a bird’s head, complete with a long beak: an exhibit thought to be a plague mask that captivates visitors to the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin. Acquired on the art market in 2006, the object has only yielded very vague information about where it was created (Germany or Austria?) and when (mid-17th to mid-18th century?).

Mask, probably worn by plague doctors, Germany/Austria, 1650/1750 © DHM

There’s no doubt it’s rare, though: there’s only one other known example, located at the Deutsches Medizinhistorisches Museum in Ingolstadt. How, then, did the mask get to become the icon of the plague, a disease that first struck Europe in 1348 and continued to stalk the continent in regional epidemics in the centuries that followed? And on what basis was the object identified as a plague mask? From historical research on the plague? Or does the identification owe more to the visual legacy of the Venice Carnival and Commedia dell’arte? It might even simply be because similar hoods and masks are a familiar sight to (younger) museum visitors, many of whom are versed in the wide cast of characters from the world of fantasy role play and movies. And, of course, historicizing (rather than necessarily historical) ‘dungeons’ – as today’s chambers of horrors are known – which have sprung up on the tourist trail in cities like Hamburg, London, Amsterdam, and Berlin.

The exhibit’s primary focus of interest is its imagined wearer, the plague doctor, who emerges as an actual historical figure and so helps bring the period to life. Similarly, the mask immediately prompts questions from visitors about the object’s function, materiality, and authenticity. So, let’s take another look: the mask is made of ochre-coloured velvet with a waxed linen lining and two ‘eyes’ made of selenite crystal (historically known in German as Marienglas, or ‘Mary’s glass’).[1] The material around these spectacle-like lenses is bordered with leather. However, the most striking feature is the long beak-shaped nose crafted from hard leather. A number of holes have been punched into the underside of the beak, which contains a meshwork of strips of leather. The object shows clear signs of use: the leather and fabric are worn, hardened, and show signs of discolouration – possibly because herbal and vinegar essences were put inside the beak in an effort to ward off ‘miasma’ (the foul air believed to spread diseases).[2] By contrast, the portion of the mask covering the top of the head is noticeably better preserved. This may be because the owner also wore a broad-brimmed hat over it, thus protecting the uppermost portion of the mask from dirt and damp. The neck and shoulder portion of the object consists of several pieces of material sewn together, forming a snug fit around the wearer’s shoulders. The example in Ingolstadt also includes a fixture at the neck for lacing up and ‘sealing’ the mask, although its counterpart at the DHM lacks this feature.

The object’s history sounds compelling: the mask would have belonged either to a university-educated physician (medicus), or a surgeon (chirurgus) who had learned his trade on the job. The mask was believed to protect the wearer from infection as he went about treating patients with the plague. This type of mask would also have been worn with a floor-length garment and leather gloves. The idea was to prevent contaminated air (or pestilent ‘vapours’) from reaching and infecting the plague doctor inside the protective wear. The wearer would also have carried a long staff with him, which was used for examining patients ‘at a safe distance’ and served to identify him as a plague doctor.

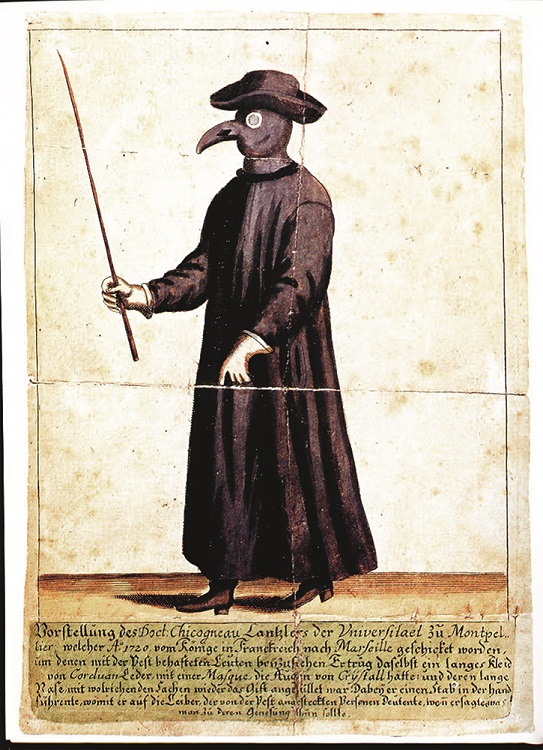

Depiction of Doctor Chicogneau as a plague doctor in Marseille, 1720 © Germanisches Nationalmuseum

However, there is a complete lack of written or visual sources from the time of late-medieval plague epidemics – in the form, say, of descriptions or instructions – to corroborate the use of protective clothing. This ‘gap’ in an otherwise enjoyable historical narrative was noted by Marion Maria Ruisinger, who has since undertaken research on the pictorial tradition of the plague doctor.[3] The first visual representation of a plague doctor dressed in this manner was published in a broadside around the time of a plague epidemic in Rome in 1656.[4] Notable for the high, upturned cloak collar and a broad-rimmed physician’s hat, the depiction recalls the figure of Dottore from the theatrical tradition of Commedia dell’arte. The print was widely circulated, and a similar illustration was published five years later in Thomas Bartholin’s Sammlung anatomischer und medizinischer Merkwürdigkeiten (Collection of Anatomical and Medical Curiosities).[5] A major plague epidemic swept through the southern French city of Marseilles in 1720, proceeded the following year by the publication of Jean-Jacques Manget’s Traité de la Peste. The plague doctor depicted on the frontispiece of this work sports headwear that bears a strong resemblance to the DHM’s mask; this image was likewise widely reproduced. However, there is no record of any plague epidemics in central Europe in the 17th and 18th century – which is to say, in the region and period from which the mask is believed to originate.

This raises a number of questions about the exhibit – questions that require historians to demonstrate their powers of historical judgement. Might there be some doubt about the object’s provenance? Is ‘Dr Beak’ even the historical figure we think we recognize? Or is it possible that the mask was not, in fact, worn to keep the plague at bay, but used in rather different contexts – carnival celebrations, for example, or even as a replica of the printed depiction (thus making it perhaps an artefact of historical imagination at the time of its making). Having first ‘gone viral’ in the period after 1656, did this undeniably attractive visual motif become so familiar that it was simply accepted at face value? And how practical would it be to actually use the mask? Could someone’s nose fit inside the beak, and would the two air holes – which, it may be worth noting, are completely absent in the Ingolstadt mask! – be sufficient for breathing? Or might the wearer have in fact risked death by suffocation in his efforts to escape the Black Death? Just how well could someone actually see through the (fairly wide-set) crystal lenses? It may be possible to shed light on some of these questions in preparation for the redesign of the permanent exhibition, which could free up the mask for further material and technical analysis. Rather than a warning from history about the risk of contagions, maybe the object stands as a reminder of the risk of contagious stories in history?

References

1 Sincere thanks to the DHM’s textiles conservator, Jutta Peschke, who closely analysed the object.

2 The plague bacillus was discovered in 1894 by Alexandre Yersin and named yersinia pestis after him.

3 Our sincere thanks to Prof. Marion Maria Ruisinger of the Deutsches Medizinhistorisches Museum, Ingolstadt, for sharing her findings. See the recently published essay: ‘Fact or Fiction? Ein kritischer Blick auf den “Schnabeldoktor”’ in: Pest! Eine Spurensuche. Exhibition catalogue published by the LWL-Landesmuseum für Archäologie, Westfälisches Landesmuseum Herne, Darmstadt 2019, pp. 266–274.

4 Der Doctor Schnabel von Rom. Kleidung wider den Tod zu Rom. Anno 1656 (Doctor Beak of Rome: Clothing against Death in Rome, 1656), printed by the Nuremberg publisher Paul Fürst. The text accompanying the print gives the following description of the protective clothing and safety measures: ‘The doctores medici thus set out from Rome, when visiting people infected with the plague, to tend to them and wore as protection from the poison a long garment of waxed cloth, face masked, large crystal lenses for their eyes, a long beak filled with sweet-smelling spices in front of their noses, carrying in their gloved hands a long rod [although the doctor in the engraving is ungloved!], with which they pointed at what the patients should do and the things they needed.’

5 Bartholin, Thomas: Historiarum Anatomicarum & Medicarum Rariorum Centuria […], vols. 5–6, Copenhagen 1661, pp. 142–145.