ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT AND THE ASCENT OF CHIMBORAZO

Following many years of painstaking preparation, Alexander von Humboldt set sail for South America in 1799. To this day, his tour of America remains one of the most famous expeditions in human history. Humboldt’s thirst for knowledge was so great that he and his companions often risked life and limb. Take, for instance, the daredevil mission that the scientist embarked upon in the early summer of 1802, when he attempted to become the first person to scale what was then thought to be the world’s highest mountain.

In the dim light of an oil lamp, Alexander von Humboldt looks up from his diary. Whilst he commits the events of recent days to paper in spite of the cold and darkness, his companions Bonpland and Montúfar are sleeping by the fire. The indigenous bag-carriers are sitting a few metres away and talking in hushed tones as the beasts of burden breathe heavily behind them. Humboldt emerges from beneath the thick woollen blanket and stretches his right hand into the pitch-black sky in a gesture of premonition and watches as his hand is slowly covered in a blanket of fine snowflakes. For a moment, he thinks he can hear a deep roar from the depths of Chimborazo before dismissing it as a figment of his imagination. Tomorrow, Humboldt plans to become the first person ever to reach the summit of the mighty Andean peak.

RESEARCH MARATHON IN THE NEW WORLD

It’s summer 1802. The expedition that has taken the two natural scientists Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland across the ocean and through large swathes of South America has already entered its third year. Their bags contain more than 50 modern instruments such as telescopes, barometers and sextants – and they already have a veritable research marathon under their belts. They have proven the existence of a channel linking the Orinoco and Amazon rivers. They have studied the flora and fauna of the tropical rainforests. They have visited the silver and gold mines of Colombia. Bonpland – a fearless Frenchman – has cheated death by a whisker more than once during the course of the expedition.

They are now making the arduous journey up the side of mighty Chimborazo. Despite inhospitable conditions, the adventurous scientists have reached an important staging post: the snow line. They rest here for a day before setting their sights on the summit of a mountain that is steeped in myth and legend. This ascent is meant to be the highlight of their current mission to explore the Avenue of Volcanoes – a series of more than 20 fire-breathing mountains in the heart of the breathtaking Andes.

HUMBOLDT AND HIS COMPANIONS BRAVE THE TREACHEROUS CLIMB

When Humboldt awakes on the morning of 23 June 1802, the fire has almost died and the camp is snowed under. The natural scientist has no time to lose, wakes his companions and urges them to get ready at the double. Bonpland and Carlos de Montúfar, who is just 21 and joined the French–German duo in Quito, are soon ready to go. The locals, however, steadfastly refuse to take another step. Their message is crystal clear: “let these crazy Europeans die alone; at any rate, this foolhardy endeavour is not possible with them.” Humboldt and his two companions brave the dangerous climb alone.

The concerns expressed by the indigenous people prove justified. There are good reasons why they and their ancestors have never crossed the snow line. They know that the higher altitudes are home to what modern-day mountaineers call the ‘death zone’ – dangerously thin air. The equipment of the Humboldt trio is woefully inadequate. Their boots are ruined and soaked, they are lacking gloves. Humboldt may be thinking ‘never mind, there’s no stopping anyone who makes it this far.’

THE EXPLORERS DICE WITH DEATH – HUMBOLDT DISCOVERS ALTITUDE SICKNESS

As they climb towards the summit, the Prussian explorer repeatedly measures the altitude, temperature and air pressure. He also takes rock samples and carefully removes plant cuttings. The higher they climb, the lower the temperatures plummet and the more sparse the vegetation becomes. As the snowfall becomes heavier and the fog thicker, Humboldt tells his companions that they should stick together. At this moment, he looks towards Bonpland and sees thick streams of blood flowing from the Frenchman’s nostrils. At first, he is only mildly unsettled until he notices that Montúfar’s entire face is covered in blood. Montúfar then suddenly starts vomiting. When Humboldt himself is overcome by dizziness, nausea and nasal bleeding a few moments later, he is sure that it’s no coincidence. The three men must be suffering from a previously undiscovered illness – ‘mountain sickness’ as he would later call it.

The dazed explorers stumble along until they are just a mere ‘three times the height of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome’ (as Humboldt would later describe it) from the top. Staggering rather than walking, the men come up against an insurmountable crevice that forces them to head back – ultimately saving their lives. Whilst they are making their descent, the snow falls with unusual severity, causing them to lose their bearings completely. They aimlessly stumble downwards, before falling – as luck would have it – into the arms of their indigenous bag-carriers. Despite the bad weather, the locals had stayed put at the snow line, bringing the exhausted explorers back down into the valley as quickly as possible. Had Humboldt, Bonpland and Montúfar continued climbing towards the summit, it may have spelled their demise.

HUMBOLDT AND CHIMBORAZO: AN AMBIVALENT RELATIONSHIP

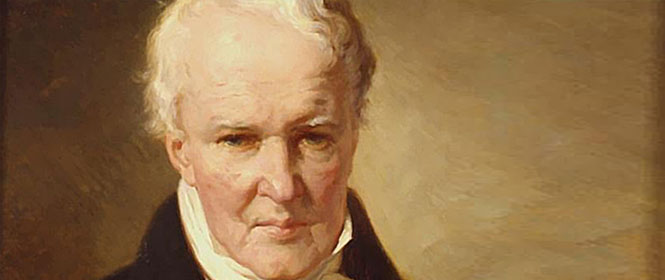

Humboldt’s great dream of being the first to scale Chimborazo had ended in failure. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to think that they had made their reckless adventure in vain: thanks to a diary entry made shortly after the trek, Alexander von Humboldt became the first person to describe altitude sickness – adding yet another discovery to his remarkable record. Humboldt’s relationship with Chimborazo, on the other hand, remained somewhat ambivalent: his narrow failure to conquer the volcano rankled with him to such an extent that he dismissed his achievements on the mountain as insignificant and downplayed them in an ironic essay. As Humboldt sat for a final portrait shortly before his death in 1859, however, there was only one possible backdrop for the painting: mighty Chimborazo. Humboldt did not live to see the first ascent, which was achieved by British mountaineer Edward Whymper in 1880 – 78 years after a crevice saved the lives of Humboldt and his fellow adventurers.