The Power of the Picture

In our column we are publishing the talk given by Andreas Platthaus, Editor of the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung”, in the Schlüterhof at the Deutsches Historisches Museum on 28 September 2017, at the opening of the exhibition “Craving for New Pictures”. The exhibition can be seen until 8 April 2018.

Allow me to begin with a few words about myself. I, too, have an enormous craving for new pictures. This may sound odd coming from a literary editor; someone, that is, whose professional field is “belles lettres” – literally, beautiful letters. I’m not simply talking about rhetorical images or figures of speech: metaphors, metonyms, allegories; or about the way we lovers of literature can be transported by “les belles images”, the creations of authors who paint images in words. No, I personally, as you may know, am always on the lookout for new masterpieces from the world of comics, cartoons and caricatures. And – since there is no future without a past, no new discovery which does not build on earlier achievements, no enlightenment which does not shed light on what is already there – I am always looking for Old Masters in these arts. For me, therefore, the exhibition in the Deutsches Historisches Museum, which we are opening today, is an eye-opener. As it will be for you too.

Comic, Cartoon, Caricature: a democratic medium at the time of the 1848 March Revolution

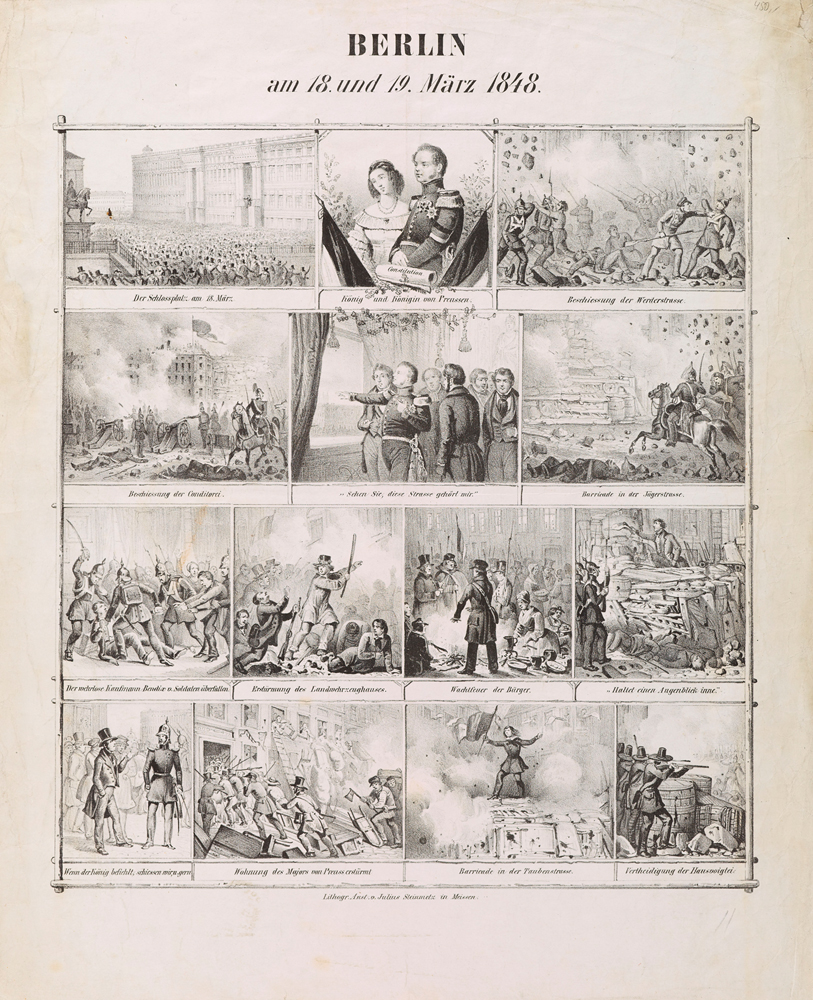

“BERLIN am 18. und 19. März 1848.” (Berlin March 18-19, 1848), Julius Steinmetz, Meißen 1848 © DHM

Let us take, for example, this news sheet, which, as far as I know, has only survived in the holdings of the Deutsches Historisches Museum. It dates from the year 1848, and if you are a little bit familiar with the prehistory and early history of the German comic, you will know that, not very long ago it would have been very difficult to convince anyone of its existence. For the general consensus was that there were no comics in Germany before Wilhelm Busch (creator of “Max und Moritz”). In fact, that consensus still holds true, in so far as there was indeed no such thing as a comic in the modern sense of the word – a series of pictures with an integrated text. And if we take “integrated text” to mean what it says: not just added written elements, but written elements which combine with the illustration to create an aesthetic unit, in other words, which are actually part of the graphics, then neither the illustrated stories of Wilhelm Busch nor this illustrated news sheet are comics. But even if we are not dealing here with the early history of the comic, we are dealing, at least, with its prehistory.

The two serial publications in which Wilhelm Busch was to publish most of his work from the 1860s onwards – the “Fliegende Blätter” and “Münchener Bilderbögen”, both issued by the publishing house Braun und Schneider – date respectively from 1845 and 1848, in other words, from almost the same moment as this picture story from our exhibition. At that time, the whole of Germany was being convulsed by the turmoil leading up to the March Revolution in 1848, a turmoil taking place not only in politics but also in journalism. The Carlsbad Decrees, which since 1829 had imposed rigid censorship on the numerous individual German states, had been relaxed, and finally became obsolete with the March 1848 Revolution. Comics, cartoons and caricatures, legacies of the liberated images of that period, still constitute a triad of enlightenment to day. Wherever they exist, we see more clearly: both ourselves and everything that makes up the society around us. Long before the concept existed, they were social media. Their “raison d’etre” is to communicate: opinions, knowledge, humour. And to do it in pictures, the most democratic medium. People may be illiterate, but everyone can understand a picture. You don’t need an education for that.

The 1848 revolution as a picture story

That doesn’t mean, by the way, that an education does any harm. Behind the fascinating story which our broadsheet here actually narrates, lies another fascinating story. For this pictorial account of the events which took place in Berlin on 18th and 19th March 1848, the apparently successful uprising against the absolutist monarchy in Prussia, didn’t appear in the country whose upheavals it records, but was instead published in Meissen, in Saxony, by the lithographic workshop of Julius Steinmetz, which normally confined itself to local affairs. In Prussia itself, the broadsheet could never have appeared at all, because, as we all know, the revolution quickly foundered. King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, always considered “a romanticist on the throne”, turned out to be a cool power politician, who, even before turning down the imperial crown offered him by the Frankfurt Parliament, made sure that the revolution ran into the sand. The dreamer, mocked as such even in this broadsheet, turned out to be something quite the opposite: a man of steely resolve.

We see the dreamer in the second picture of the sequence, a picture implying a “Sleep of Reason” à la Goya: his eyes closed to what he doesn’t want to see. Although it is the second picture, it is the first one we notice: the King and Queen of Prussia, caught, as it were, between two fronts, symbolised by the black and white colours of Prussia on the left and the black, red and gold banner of the revolution on the right. In the picture to the left we see the masses gathered on the square in front of the palace, while the picture to the right moves swiftly on to a scene with troops opening fire in Werderstraße. This event was the result of the King’s order, on 18th March, to clear Schlossplatz in front of the palace, causing the situation in the capital to escalate. In our illustrated news sheet, we can follow events as they unfolded: troops opening fire on the confectionery shop, barricades in Jägerstraße, the unarmed shopkeeper, Bendix, attacked by soldiers, the storming of the Arsenal, and so on. In the midst of it all we see the King, in the second picture in the second row. As he surveys the scenes of uproar around him – closing in on all sides, like the pictures themselves – he remarks: “Look, this street belongs to me.” But he’s the only one who sees it that way. Of a total of three pieces of dialogue in the news sheet, the first one thus represents hubris. The second documented remark represents reason – “Stop! Think what you’re doing,” spoken by a prudent citizen, and the third – spoken from the mouth of an arrogant officer – blind obedience: “When the King orders, we gladly shoot.” It is all too clear which of these three attitudes the anonymous illustrator sympathizes with. Who can this artist have been? The Berlin local historian, Margret Dorothea Minkels, thinks the originator of this illustrated broadsheet may have been Julius von Minutoli. That would indeed be sensational, since Minutoli was none other than the then Chief of Police of Berlin, whose moderate stance towards the March revolutionaries brought him into disfavour with the King and resulted in his having to resign when, three months later, the next great revolutionary rising occurred: the storming of the Berlin Arsenal, the very building in which we are sitting now. Minutoli left Prussia and spent three years in exile in Lower Franconia (Bavaria), where he spent some of his time drafting his memoirs of the turbulent events of 1848.

In his case, we must take the word “drafting” literally, for Minutoli was a gifted draftsman. The examples given by Frau Mingels in her books do, indeed, have certain things in common with our broadsheet, especially the way the pictures are framed by an illusionistic structure of beams, a device which represents an early step towards the characteristic architecture of today’s comic strip and the layout of graphic novels. Unfortunately, from our perspective of hindsight, these beams seem to represent not just a framework for the action, but a boundary, fencing in, once again, what, just for a moment, had seemed about to be set free. Thus, the very composition of our illustrated broadsheet demonstrates the historical dilemma of its subject. Pictures quite often know more than their originator and, consequently, we therefore usually know more about them than about him or her.

The Spanish Civil War: Picasso portrays Franco fighting the Republican government

There are exceptions. This is one of them.

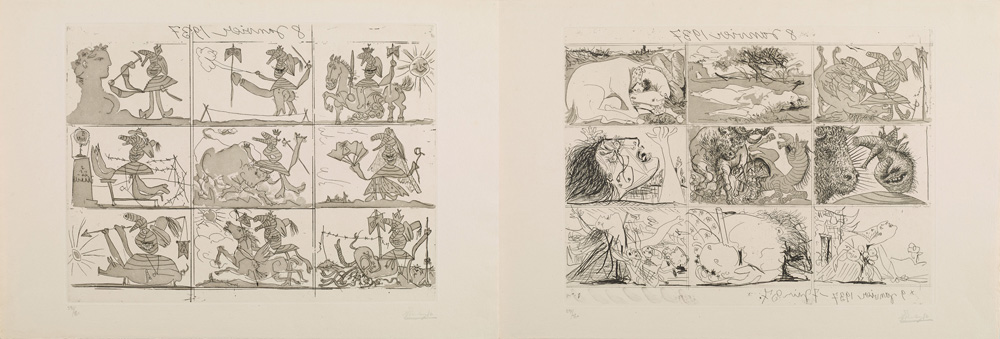

Sueno y Mentira de Franco (Planche I-II), Pablo Picasso, Paris 1937 © DHM

Its creator is much better known than his work, something which is immediately apparent. Pablo Picasso is represented in the exhibition by two aquatints from the year 1937, telling the story of the “Dream and Lie of Franco” – an artistic protest against the civil war in Picasso’s home country of Spain. Yet, there is a third sheet which belongs with these two picture narratives. It is almost never put on display or even mentioned, because it is simply a sheet of text, a poem printed in three languages, in which Picasso, writing in the Surrealist style of “écriture automatique”, without any punctuation marks, uses the technique of ‘free association’. Here is just the beginning: “fandango of shivering owls souse of swords of evil-omened polyps scouring brush of hairs from priests’ tonsures standing naked in the middle of a frying pan placed upon the ice-cream cone of codfish fried in the scabs of his lead-ox heart…” and so on and so forth. It sounds baffling, and that’s why we are usually spared the trouble of trying to understand it and instead shown only the graphic works, which we find more accessible than the imagery of these strange words. I find that painful, however, not only as a literary editor, but also as an avid lover of new pictures. For in 1937, Picasso was trying to forge an aesthetic association of picture and word, whose precise intention was to alienate. If we dissolve that association to make things iconographically more comfortable, we are once again betraying the new.

Savage representations: criticism of Prussian expansionist ambition

“LE GRAND ÔGRE ALLEMAND.”, Pinot & Sagaire, Épinal 1866/1871 © DHM

Setting text and image side-by-side instead of putting them one inside the other, and thus really combining them – one of the design principles later to be embodied in the comic – is a sour fruit of the Reformation, when the power of the Word triumphed over the power of the image. However much that religious struggle may have fired the craving for new pictures through its broadsheets, it nevertheless inflicted lasting damage on something which earlier had been taken for granted: the integration of picture and text, known, for example from religious pictures – for example the “Biblia Pauperum”, church windows and communion vessels. The caricature inherited this separation, but broke new ground in the extreme nature of its illustrations. Franco’s dream wasn’t exactly a pictorial lullaby, but just have a look at this gentleman from the period when Franco-German rivalry was reaching its height, just before the war of 1870/71. It’s not hard to see that it’s about Wilhelm I, who had succeeded his brother Friedrich Wilhelm IV, that dark-horse “romanticist on the throne”, who had latterly fallen victim to mental illness, as King of Prussia. It’s not difficult, either, to recognise the picture which had inspired the now unknown caricaturist: Goya’s late oil painting of Saturn devouring his own children.

Here we see “Old Kaiser Wilhelm”, as he was later to be fondly known, as a young man, stuffing his mouth with a snack from the pannier on his back, in which he has collected up all the German princes whose territories, such as Hanover, Hessen-Kassel and Nassau, Prussia had annexed in 1866. A broadsheet like this could not have been published in the North German Confederation, just being established at the time, nor in the southern states which still, for a short time, retained their independence. But in France it could, and “Le Grand Ôgre Allemand” – “The Great German Ogre” – turned out to be prophetic, since a few years later the new German Empire swallowed the French provinces of Alsace and Lorraine and crowned William as Emperor of the new German Reich.

For and against the war: the terrible Prussian brain

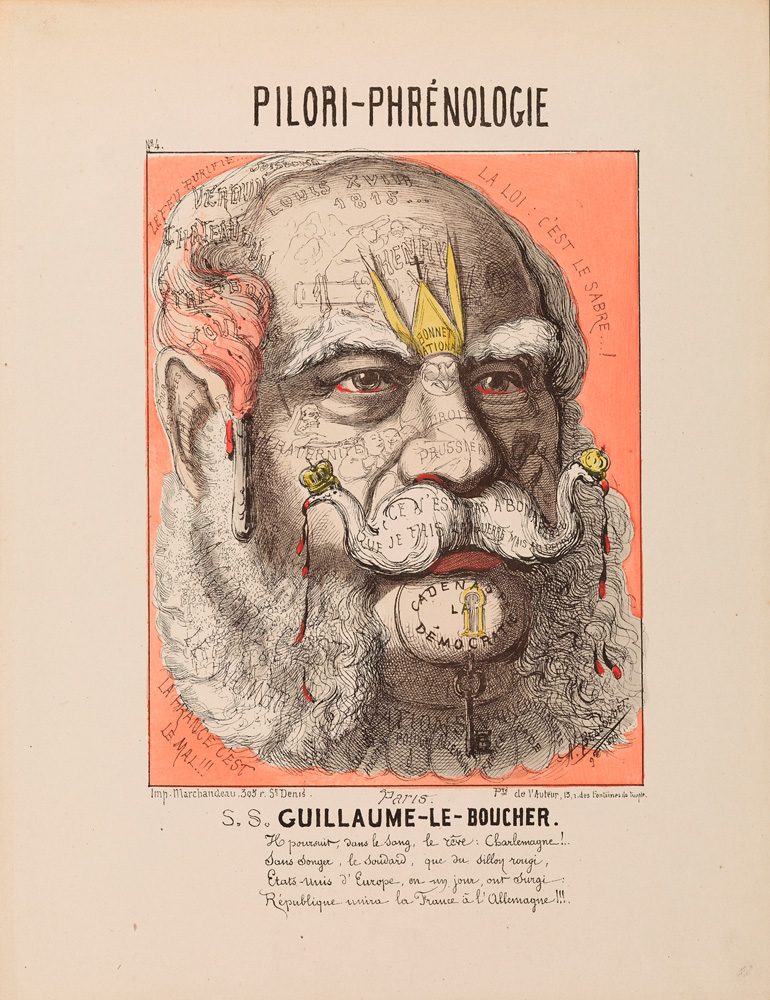

“PILORI-PHRÉNOLOGIE. / S.S. GUILLAUME-LE-BOUCHER.”, André Belloguet, Marchandeau, Paris 1870 © DHM

The war which yielded this rich booty also generated another blood-thirsty caricature, again showing Wilhelm of Prussia. Drawn in 1870 by André Belloquet, a fervent French republican, this image of “William the Butcher” was, as its title announces, one of a series of lithographs issued under the name “Pilori-phrénologie”: “Pillory – Phrenology”. What is being autopsied and mapped here is Prussian absolutism. On William’s skull is inscribed the name of Louis XVIII, the French king who had restored Bourbon rule after the revolutionary era. Prussia, France’s enemy in war, has assumed the legacy of the enemy of the French people. And the legacy of the greatest adversary France had ever known: the English King Henry V of the Hundred Years’ War – his name, “Henry V”, is inscribed on the Prussian ruler’s forehead. A padlock bearing the inscription “democracy under lock and key” is affixed to William’s mouth: freedom of speech is over. Blood drips from the beaks of the eagles’ heads formed by the tips of his moustaches, and on the bridge of the German enemy’s nose sits a bishop’s mitre – symbol of the unenlightened ruler. Belloquet has drawn a horrific figure, and he himself obviously suffered from “horror vacui”, since there is not a quarter of a square centimetre of his defamatory broadsheet without an inscription. Here word and picture really are inseparable.

Satire today: Charlie Hebdo and political-religious conflict

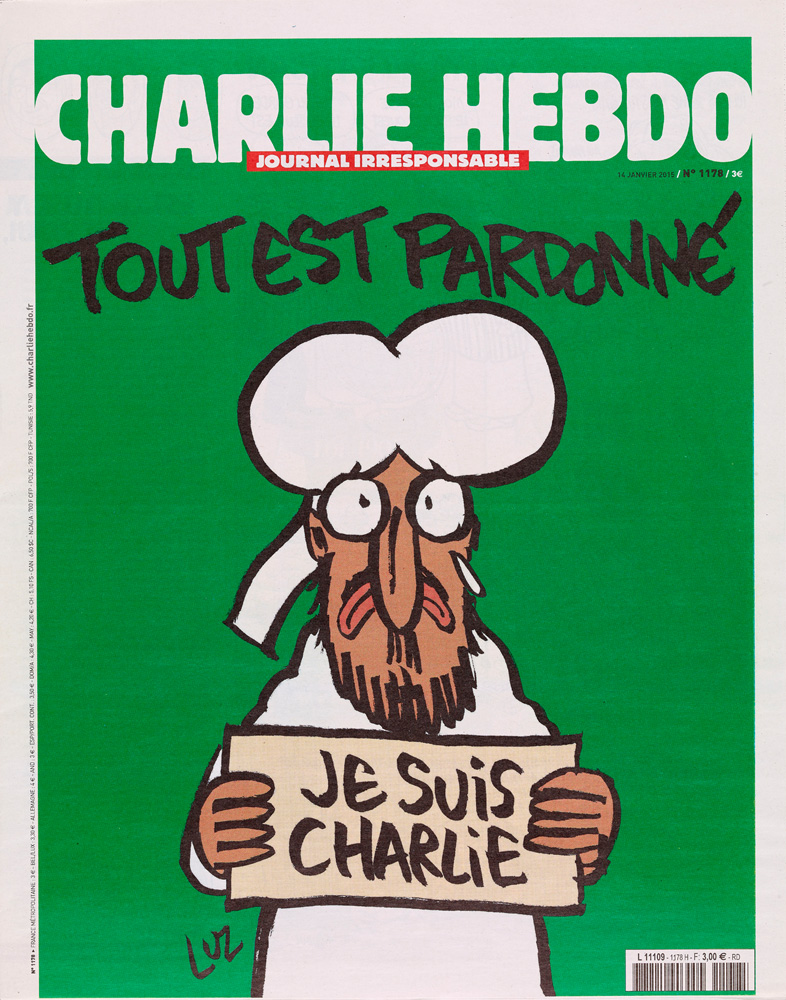

“TOUT EST PARDONNÉ / JE SUIS CHARLIE”, Luz (Rénald Luzier), Paris, 14. Januar 2015 © DHM

As they are, one and a half centuries later, in the most recent caricature displayed in the exhibition. Since it is the title page of the edition that sold the most copies ever in the magazine’s history – over eight million – it is probably also the most widely distributed work of its genre – and quite definitely the most controversial. It was drawn by Renald Luzier, alias Luz, for the first edition of the satirical journal “Charlie Hebdo” to appear after the massacre of its editorial team on 7 January 2015. Luz had escaped death because 7 January was his birthday and he had therefore arrived at work later than usual. He was chosen to draw the cover for the edition immediately following the attack, because, apart from his colleague Riss, who was wounded and therefore unable to work, all the other title-page artists on the payroll – Charb, Cabu and Tignous – were dead. A year later, Riss recalled the circumstances in which this edition had been hastily put together:

“Everything we had experienced together over the past 23 years gave us the necessary fury. Never before had we so badly wanted to silence everyone who had dreamed of getting rid of us. Those two little masked idiots were not going to succeed in scattering our life’s work to the winds, all the wonderful moments we’d spent with those who had died. They weren’t going to succeed in burying Charlie.”

These are implacable-sounding words.

The message on the title page has therefore given rise to a great deal of head-scratching: “Tout est pardonné”. But who was forgiving whom here? Were the editors forgiving Islam, whose representative is siding here with “Charlie’s” sympathisers? Was the Prophet forgiving the magazine? Or did this represent some sort of divine general amnesty for the murderers? The ambiguity was too much for some observers, who either accused the surviving editors of grovelling to Islam or, conversely, of further provocation, since, after all, were they not only once again portraying the Prophet, but going so far as to show him holding a declaration of solidarity for the magazine which Islamists hated? Nothing in the accompanying text, however, suggests that the picture is actually of Mohammed at all. It’s true that the background is green, the colour of the Prophet, and that the iconography of the figure, with beard and turban, follows the Mohammed clichés common since the fracas over the Danish caricatures in 2005. Yet the white robe is more likely to identify the figure as one of the spiritual leaders of Islamic extremism who had already appeared in countless caricatures by “Charlie Hebdo”, most of them also leaving deliberately unclear whether the figure was actually Mohammed himself.

Picture and word: the power of the alliance

As civilised museum visitors, we take debates of this sort in our stride, but doing so won’t stop the misuse of the pictorial inventions we love. Our craving for new pictures may be great, but the bloodlust of fanatics is greater still. It is not as great, however, as the power of pictures themselves; that is why religions have been so diligent in banning them. The conflict between enlightenment and religion is an essential component of the story which this exhibition tells – in part through anti-Semitic illustrations, which crop up again and again in the exhibition, and which are making an appalling comeback today. The front line between new pictures and old beliefs runs right through the middle of art history.

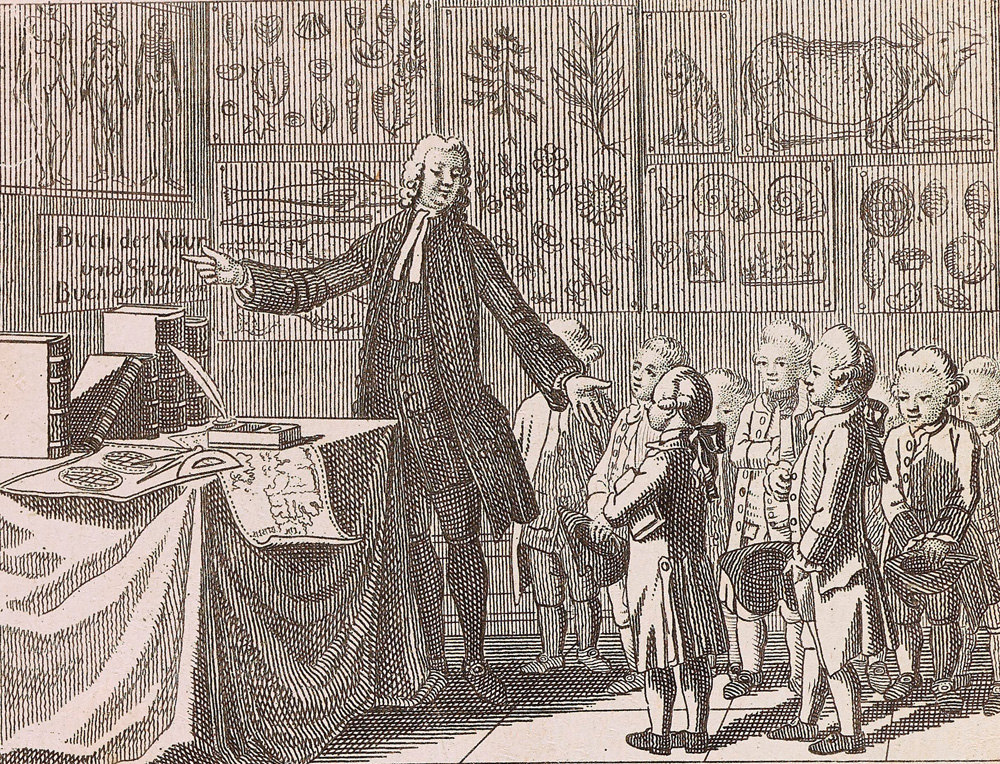

Picture boards in school, Daniel Chodowiecki, 1774 © DHM

Daniel Chodowiecki, the greatest satirical engraver of the Prussian enlightenment – and an artist, by the way, as guilty of stealing the ideas of competitors as they were of stealing his – knew that only too well. That was why, in 1774, he drew a teacher using a then modern innovation to instruct a group of pupils: picture boards. The schoolmaster’s finger, however, is pointing to the written word in its traditional form: we read “Book of Life and Morals”, and “Book of Religion”. The conflict between belief and enlightenment, seriousness and mockery, word and picture is old, and even this exhibition won’t resolve it. But the exhibition does show just how much pictures have achieved – and that their most impressive achievements have occurred when they have formed an alliance with words – and against any authority which claims to pronounce “the one true Word”.

|

Andreas PlatthausAndreas Platthaus was born on 15 February 1966 in Aachen. After a banking apprenticeship in Cologne, a degree in business studies in his home city, and reading countless Donald Duck stories, he lost any desire to succeed in private enterprise. Instead he went to study rhetoric, philosophy and history in Tübingen, so as to become rich in knowledge, at least. He started work on the arts pages of the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” in 1997, where he is now the literary editor. In addition to this job, he is actively involved with the “Donaldists”, and became an honorary member in 2007. Since 1998 several books have appeared under his name, including the biography, “Alfred Herrhausen – Eine deutsche Karriere” (2006), the novel “Freispiel” (2009) and, in 2013, his historical study, “1813 – Die Völkerschlacht und das Ende der alten Welt”. |