Censorship in Germany

The media and wider public have for several weeks been discussing a possible new form of censorship in Germany. The issue in question is the controversial Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz (“Network Enforcement Act”), which came into full legal force in the New Year. The law does not create any new offences, but is instead designed to ensure statements made on the internet that contravene existing laws – for example, instances of libel or incitement to racial hatred – can be prosecuted more effectively. Unfortunately, it led to operators of some social networks deleting large numbers of entirely legal expressions of opinion one day after the law came into effect. While experts debate whether this should be considered an act of state censorship or, rather, overzealous self-censorship by the affected social media platforms, the historian and media scientist Benjamin Mortzfeld takes a look back at the undisputed facts of the history of censorship.

Fake News and Indecent Pictures

During most periods of German history, the press has been strictly monitored. As early as 1548, the authorities in the Holy Roman Empire were compelled by the Augsburg Imperial Diet “to allow nothing to be printed that is repugnant to Catholic teaching or might provoke unrest. Books, writings, paintings, metal casts, wood carvings, and models that offend in this way should be confiscated and, as far as possible, suppressed.”[1] The situation was largely unchanged some two hundred years later.

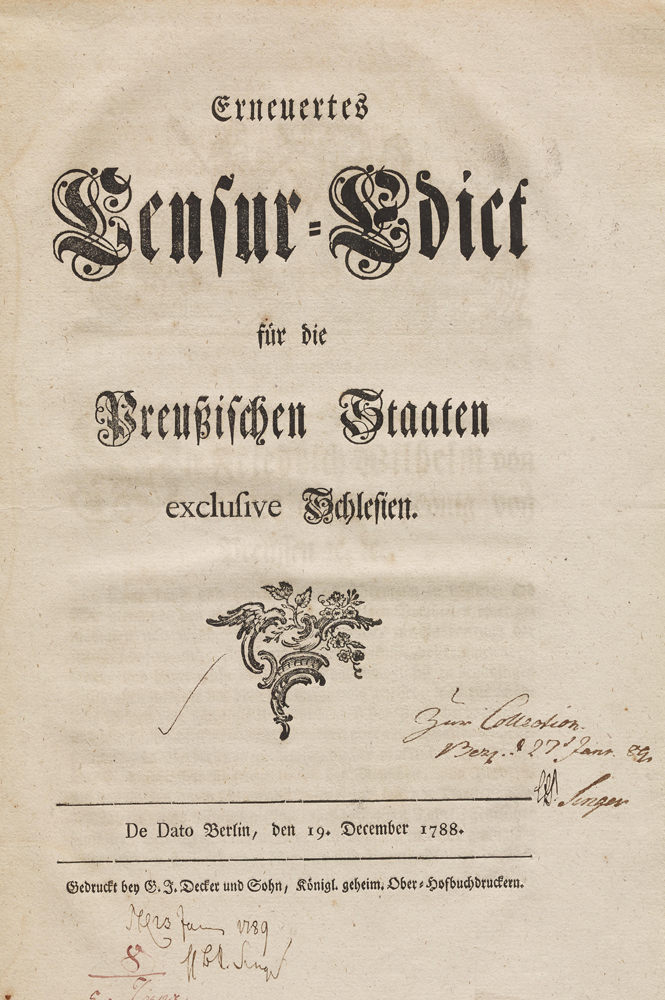

Renewed Censorship Edict for the Prussian States Exclusive of Silesia, 19 December 1788 © DHM

In the “Renewed Censorship Edict for the Prussian States Exclusive of Silesia” (1788), King Friedrich Wilhelm II gave the following justification for the new laws: “What manner of damaging consequences would result from unlimited freedom of the press, and how often might it [be used] by foolhardy or even malevolent writers to spread practical errors about important human matters, corrupt morals with indecent images and seductive portrayals of vice, or give voice to derisive mockery and malicious criticisms of public institutions and directives.” The problems cited by the king continue to be used to this day to justify interventions by the state: the media, so it is claimed, are full of “fake news”, pornography, and criticism of the government, and so pose a risk to social stability. State censors in Prussia therefore monitored all publications, and all forms of printed material – both pictures and text – had to be submitted to “preliminary censors” for approval. While authors of academic works enjoyed more room for free expression, critical statements of a political or religious nature were officially discouraged. Consequently, Germany for a long period lacked any opportunities to develop a culture of political cartoons and satire.

“Freedom of Imagery”: The (Brief) Period of Uncensored Pictures

It was only after King Friedrich Wilhelm IV’s accession to the throne in 1840 that there finally seemed to be some prospect of restrictions being relaxed. On 28 May 1842, the monarch granted freedom of expression in pictures and cartoons. The “preliminary censor” was abolished, and illustrators made the most of the new political climate. Within a just few months, around 80 political cartoons had been published – some of which took aim at the theme of censorship itself.

The Introduction of Censorship in Germany, Johann Richard Seel, Julius Springer, Berlin 1842 © DHM

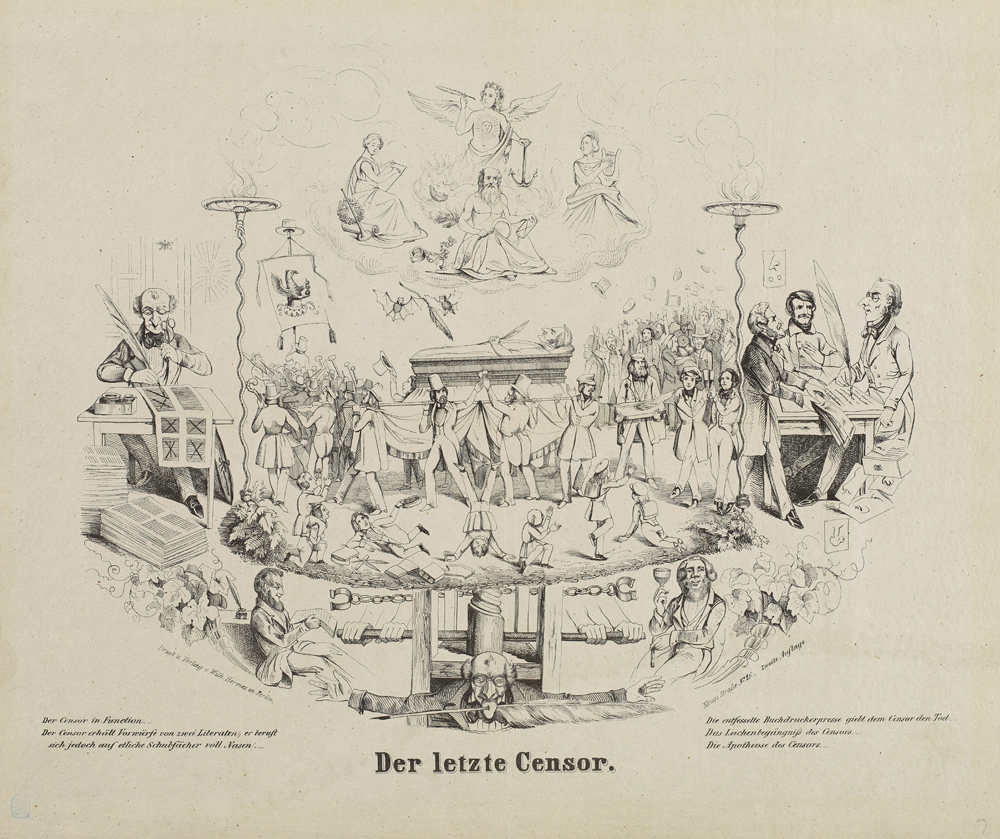

While “The Introduction of Censorship in Germany”, a satirical work by Johann Richard Seel, looks back at the draconian measures introduced as part of the Carlsbad Decrees in 1819, the picture entitled “The Last Censor” (printed by the Berlin publisher Wilhelm Hermes) celebrates the bourgeois print press’s victory over the censor.

“The Last Censor”, Wilhelm Hermes, Berlin 1842 © DHM

However, this brief dawn of press freedom came to an end in February 1843. The king issued new censorship regulations and used retroactive measures to confiscate irreverent cartoons. The examples shown here escaped destruction and currently feature at “Craving for New Pictures – From Broadsheet to Comic Strip”, a special exhibition that explores the early history of the illustrated press. Visitors to the exhibition can also see many additional examples from the realms of biting political satire and propaganda, sensational news, education, and humorous entertainment.

Censorship Then, Censorship Now?

This brief episode of “freedom of imagery” heralded a sea-change, but it was a long time before the Enlightenment ideals of a free press and liberty of expression were able to gain a permanent foothold in German states. The original pioneers of these ideals were Great Britain, France, and the newly founded United States of America. In Germany, press freedom first became a guaranteed constitutional right with the promulgation of the Federal Republic’s Grundgesetz (“Basic Law”) on 24 May 1949. However, it should be noted that “retrospective censorship” remains possible even within the purview of the Basic Law. If a publication breaks existing laws, it can be banned and might potentially result in the author or publisher being prosecuted. This applies primarily to content judged unconstitutional, libellous, or harmful to young people. However, the Network Enforcement Act means that the onus of deciding whether or not a statement made on social media should result in prosecution shifts from the state to employees of the company operating the site, who will in turn act according to the company’s commercial interests. This is in my view extremely problematic, and the law should be revoked or least thoroughly revised.

Quote

[1] Quoted in Kunze, Horst: “Gefährlicher Bilderdruck. Zur Bilderzensur, besonders im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert”, in: “Jahrbuch der deutschen Bücherei”, vol. 19, Festgabe für Helmut Rötzsch zum 60. Geburtstag, Leipzig 1983, pp. 78–79.

|

Benjamin MortzfeldBenjamin Mortzfeld (born 1984), freelance author, historian, and media scientist. His most recent role has been as the curator of the Deutsches Historisches Museum’s “Craving for New Pictures – From Broadsheet to Comic Strip” exhibition. |