Europe and the Sea

The sea separates Europe from the rest of the world, but connects it at the same time. Professor Jürgen Elvert, from the Historical Institute of the University of Cologne, describes for the Blog Parade #DHMMeer the close relationship that Europeans have been cultivating with the sea for centuries, and which is particularly noticeable in the port cities of Europe.

As a realm almost criminally neglected by historians to this day, the sea offers an alternative way of approaching European history. After all, about 70% of the planet is covered by water, 80% of the global population (and rising) lives by the sea or near it, and about 90% of world trade is transported by sea. In terms of the ratio of coastline (over 110,000 kilometres) to surface area (around 10.5 million square kilometres), Europe is the most maritime of all continents. In ancient times, Europe was opened up by sea, when seafarers and merchants from the Mediterranean piloted their ships through the ‘Pillars of Hercules’ into the Atlantic Ocean and sailed northwards. The sea separates Europe from the rest of the world, but connects it at the same time. To a certain extent, it has the role of a link between Europe and the world because Europeans opened up the world by sea. Secondly, the knowledge and experience gained overseas were brought back by seafarers to Europe and began to have an effect here, bringing changes for the inhabitants of the ‘Old World’ in turn.

Europa on the bull, 500–475 v. Chr. © bpk / Antikensammlung, SMB / Johannes Laurentius

Port Cities as Nodes in a Global Network

In its capacity as a medium connecting Europe and the world, the sea allows us to illustrate new perspectives and to formulate new topics of discussion. Among other aspects, we ought to consider the importance of port cities and ports. Even today, port cities are still the nodes of a network that links Europe to other parts of the world. They have always been hubs for the movement of goods and people, as well as centres of nautical knowledge. In the past, port cities were places where information originating inland was gathered, where it was discussed and perhaps modified, or even transformed, before spreading to every corner of the world. Conversely, information from overseas arrived first in the port cities of Europe, where it could be evaluated before being passed on to inland regions. The impact of new ideas and things was therefore usually felt in the port cities first. Even though the introduction of modern types of communication technology has reduced their importance as points where global lines of communication meet, ports still handle a continuous stream of both import and export goods. Their typical infrastructure and social structure, which evolved as Europe underwent the transformations of the modern age, still provide the most suitable framework for the transhipment of such goods and so the port cities continue to benefit significantly from this function.

View of Seville, c. 1600, unknown Spanish artist © Museo Nacional del Prado

By their very nature, port cities are cosmopolitan. This open-mindedness is evident in the behaviour of those who live there. Their willingness to engage with something new and to fit it into existing structures, ways of thinking and patterns of behaviour is generally greater than that of the inland population. It is no coincidence that on countless occasions throughout history, the intellectual and cultural avant-garde has flourished above all in port cities. They are centres of commerce, communication, knowledge transfer and cultural exchange, as well as political and economic power. They provide us with good examples for illustrating processes of development over the medium and long term, as well as geographic and factual connections, while giving due importance to the role of the sea.

Influences from Overseas

Port cities were the places where goods imported from overseas first arrived in Europe. They were hotbeds for the spread of non-European things that would change Europe for ever. Thus the import of new crop plants to Europe not only led to new eating habits and consumption patterns, but also to lasting changes in the European cultural landscape as a whole. I am thinking, for example, of the various fashions inspired by Orientalism, of the evolution of European tea or coffee-house culture, and of the cultural consequences of tobacco consumption. Is anybody reminded of America when they see tomatoes?

Port cities connect the sea and the coast with the regions inland. It was from them that goods from outside Europe spread far into the ‘Old World’, where they sometimes had startling consequences. One such case is the button industry in Thuringia, Germany, which specialises in making buttons from mother-of-pearl, sourced from Oceania. Another concerns the blacksmiths of Solingen, who manufactured most of the machetes used by slaves to cut sugar cane in the ‘New World’.

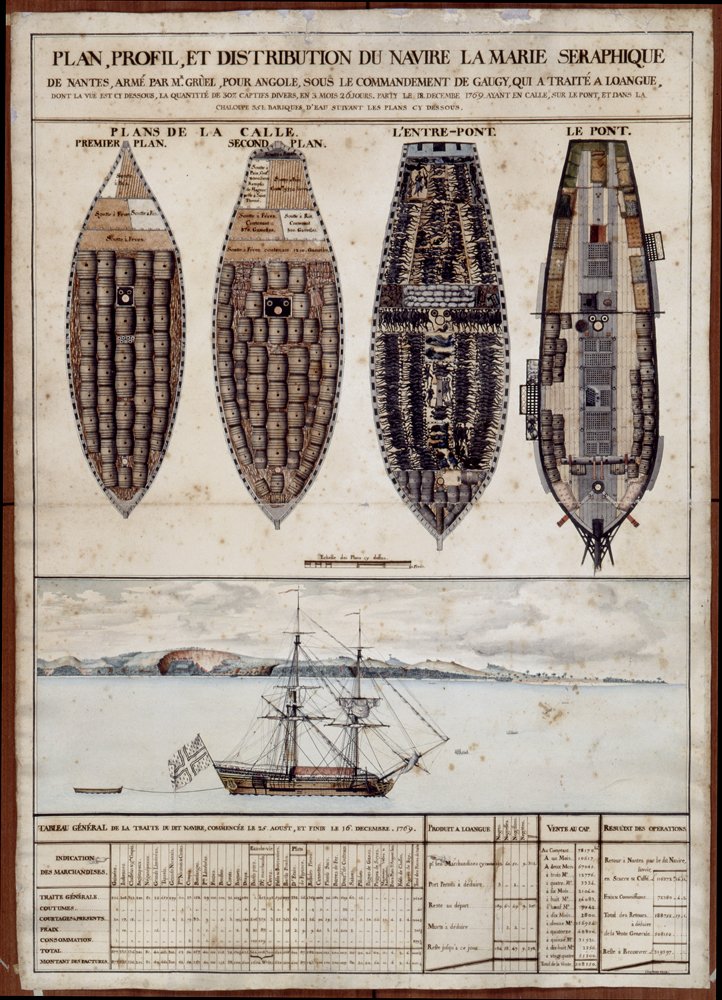

Jean-René Lhermitte, Layout, profile and transactions of the slave ship Marie-Séraphique, c. 1770, um 1770 © Château des ducs de Bretagne – Musée d’histoire de Nantes

Ordinary people and their activities shaped European civilisation as we know it today. They had a similarly lasting influence on the course of world history – not in the sense of ‘Europeanising’ the rest of the world, but as actors in a process of exchange that went on for centuries and mostly took place via the sea. It can be seen as a kind of dialogue between Europe and the rest of the world, which equally shaped the contours and character of both, and to this extent brought Europe and other parts of the world into new relationships with each other, bringing them closer in a way. The sea served as an intermediary in all this, linking parts of the Earth that had largely been separated by their respective geographies up to then, and linking the fates of their inhabitants. This process of globalisation reveals not only that European civilisation has a maritime foundation, but that every other civilisation involved in the process does too. At the moment, awareness of this fact seems to greater elsewhere than in Europe itself.

The Sea as a Borderline Experience

Thomas Mann once described the sea as providing an intimation of eternity. This is probably a key to the fascination that the sea has exerted on many people in Europe – especially since the Age of Romanticism – and continues to exert today. Another concerns the conflicting emotions evoked by the sea, in contrast to our factual knowledge of it – so whatever people’s reaction when they contemplate the sea, it is seldom indifferent. The so-called borderline experience may be an important part of this phenomenon. It can take many forms, be it a sense of the sea’s supposed boundlessness, or the confrontation with an untameable, elemental force, from which the works of mankind can never provide full protection. Others view the sea as a bridge to distant shores, where people live much better and more freely than within the straitjacket of European customs and conventions.

These reasons, among others, have motivated millions of people to board ships and to set out across the sea from Europe for foreign shores. Those who survived the voyage brought European values and conventions, knowledge and ways of life to their new homes – and altogether to almost every part of the globe. Those who returned to their native shores brought awareness and experience that they had gathered abroad, thus contributing to the growth of knowledge and prosperity in Europe. Furthermore, they had learned to see Europe from the outside, through the eyes of others, which gradually gave Europeans a better understanding of themselves – and of others. Europe discovered the world via the sea and, in the process, came to know itself.

© Private |

Jürgen ElvertJürgen Elvert was born in 1955. He is a professor (Universitätsprofessor) teaching Modern and Contemporary History at the Historical Institute of the University of Cologne. His teaching and research focus on European history, the history of European integration, and the cultural history of the sea and seafaring. Among his publications are several standard reference works. In 2013, he was awarded the honorary title of ‘Jean Monnet Professor of European History’ by the European Commission in recognition of his project on ‘European History in Global Context’, which examines European history as a part of global maritime cultural history. |