What are human rights?

Seventy years ago, on 10 December 1948, a large majority of the United Nations voted for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Our author, the historian Robert Kluth, explains how the declaration came about and asks why this valuable achievement is known to so few people in Germany.

Almost half of the German population knows little or virtually nothing about human rights. In a recent representative research poll, 48 percent of those questioned stated that they had “only a little or no knowledge of human rights”. At the same time, human rights are frequently named in current debates.

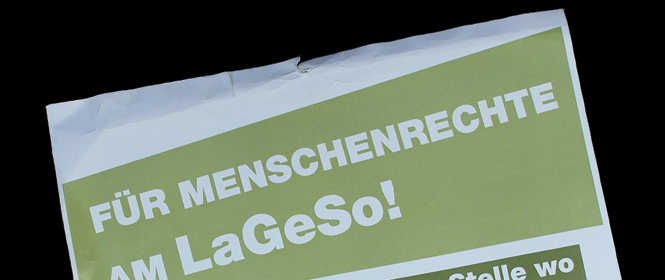

Transparent der Initiative “Moabit hilft”, von einer Demonstration auf dem Gelände der LaGeSo (Senatsverwaltung für Gesundheit und Soziales), Berlin, Januar 2016 © DHM

Why are we talking about something which more than half of the Germans admit they really know nothing about?

The individual is more important than the state or the community

Exactly 70 years ago, on 10 December 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN) passed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

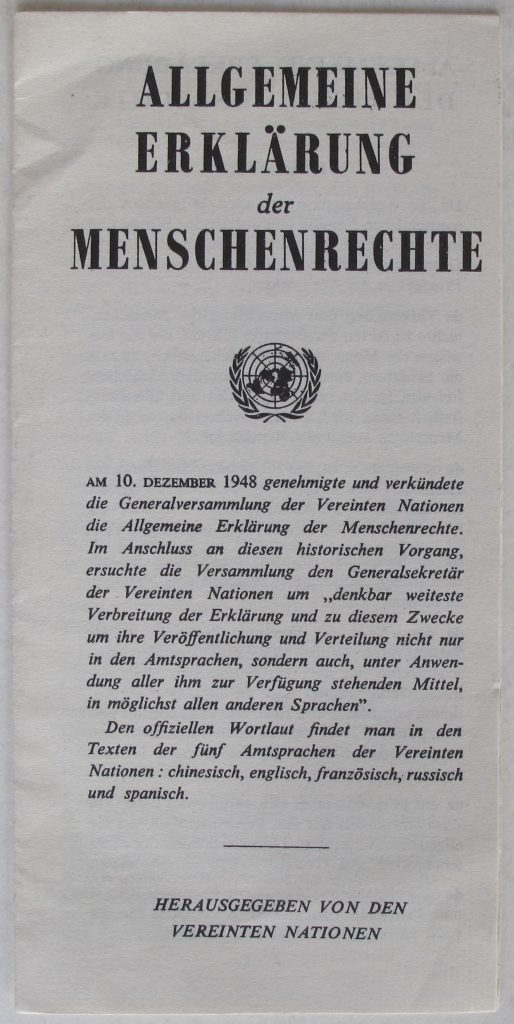

German version published in a flyer with the text “Allgemeine Erklärung der Menschenrechte“, announced by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948 © DHM

The declaration states in Article 1:

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

Being human is reason enough to be treated equally, no matter where he or she comes from, no matter what gender, no matter what age he or she has. Human rights mean, as the journalist Martin Klingst explains, “that every person may lead their own life and make their own decisions. In short, they have the right to be their own person.” The 30 articles of the declaration establish, among other things, the right to life, liberty, exile, freedom of opinion and expression, freedom of religion, privacy, health, nourishment, suitable living quarters, but also the right to work and to have periodic holidays. The great majority of the United Nations General Assembly voted for the declaration, with 48 in favour, none against, and 8 abstentions. In this way the governments agreed to set limits to their own power.

Until the Second World War there was international consensus that states should not interfere in the matters of other states. The individual state was said to be sovereign. But the crimes of Nazi-Germany and of the Second World War had made it clear that the national state had failed guarantee civil rights. The declaration of 1948 therefore represents a radical turning point in international law. For the first time the individual was recognized as the bearer of rights and obligations. The human rights protect the individual from his or her own state.

Where does human right come from when no one creates it?

From a historic standpoint, human rights are of Western origin. There are similar principles in all world religions, but the human rights as such were first formulated at the end of the 18th century in the American and French Revolutions. The French Revolution of 1789 with its Declaration of the Rights of Man changed everything – in Germany as well. For a long time people fought against these rights.

Two fundamental thoughts contained in the idea of human rights were radically new. First, the individual, a single person, takes precedence over the community. Logically the individual first has to be there before the community can be formed. And second, it is reasonable to adopt a universal human right because otherwise no peaceful coexistence is possible.

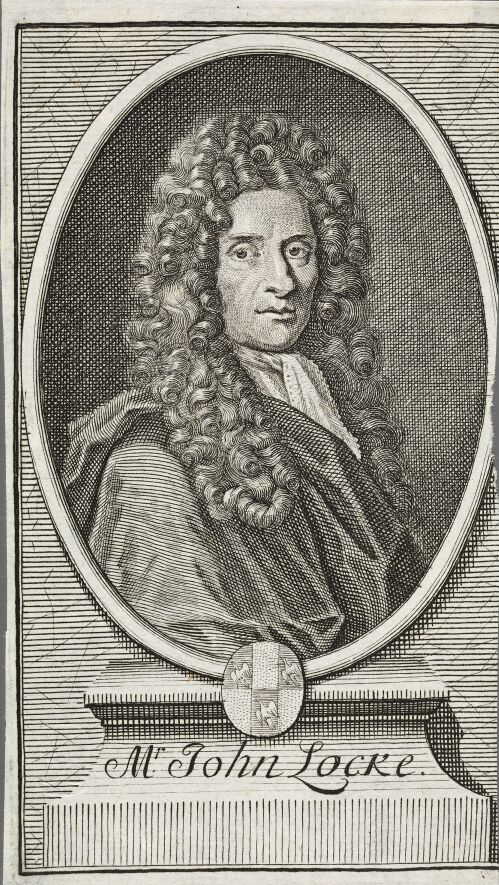

The decisive philosophical thoughts come from the 17th century, from the time of the Enlightenment. Shortly after the “Glorious Revolution” in England, the philosopher John Locke published his book “Two Treatises of Government”, dated 1690.

Portrait of the philosopher John Locke, 1651/1675 © DHM

Here Locke formulates his thoughts about human nature: What is the human being really – what is his essence? He presents the individual in the “state of nature”, without rule, social bonds or governing state. In this condition all people are free and equal, according to Locke. He calls this primal freedom and equality the “law of nature”. Since violations of the rules are not punished in this state of nature, Locke sees that reason dictates that people will leave this state of nature and are “willing to join in society with others”.

The community that is thus formed – the state – is there for the purpose of guaranteeing the laws of nature for every individual: in this state the life, health, freedom and property of fellow human beings are respected and protected. If an infringement of the rules of society takes place, it will be resolved and punished by a higher jurisdiction. The state is only a vehicle to secure the laws of nature. The laws of nature have precedence over all statehood and also over all culture – they lie founded, according to Locke, in the nature of man.

Up until the present day Locke’s thoughts on human rights have constitutive power: his philosophy of natural law is the model for the “Declaration of Rights” of the USA from the year 1776. Every inhabitant of the nascent United States of America was supposed understand this idea. For this reason the Declaration of Independence was also printed and disseminated in German for the German-speaking immigrants. One of the first prints of the Declaration of Independence in German can be seen in the Permanent Exhibition of the Deutsches Historisches Museum.

One – two – many human rights

After the UN declaration of 1948, human rights became the “most powerful political idea of the present”, according to the constitutional law expert Josef Isensee. In 1993, at the UN World Conference on Human Rights, 171 of 186 members placed their signatures under the sentence

“All human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated.”

In the meantime the list of human rights has grown. The so-called rights of defence against the state – about which Locke spoke – are now considered the minimum standard: if someone’s freedom is taken away, i.e. they are put in prison, the reason for it must be given. With the idea of communism the “second generation” of human rights was established. It lays down cultural and social participation rights for the citizens. Decolonisation and the attempt to overcome the desolate situation of the developing countries triggered a debate about the rights to development, peace and self-determination. These innovations were brought into the stipulations in the 1960s as the “third generation” of human rights.

Although human rights have become “customary international law” (Riedel) since the 1980s, they are still being called into question. It is always possible to find reasons for why people do not have to be treated equally. The renewed flare-up of nationalism argues that certain peoples have a different nature than other ones: there cannot be a single uniform law of nature for all peoples. In this way nationalism justifies the unequal treatment of people, and places the community above the rights of the individual. Regional majorities are pitted against universal rights so that human rights suddenly look like utopian foolishness. The current global political situation therefore seems to have no room for human rights.

To foster human rights means to relate history

What “human nature” actually is remains controversial. History, on the other hand, teaches us that it is sound and smart to treat people as if they are all equal and free. This idea, beyond all culture, has opened the way to discussion and encouraged a variety of opinions. Anyone who strolls through the Permanent Exhibition can recognize that history also means that everything could have turned out completely differently than it has. The American philosopher Richard Rorty has therefore demanded that there should be an end to the explication of human nature as a basis for justifying human rights. Rather, one should cultivate sympathy for these rights by relating the right stories. German history provides enough material for such narrations.

© Privat |

Robert KluthRobert Kluth is a historian and exhibition curator and has worked for german and american museums. He taught history and philosophy at a Berlin grammar school. You can contact him via Twitter. |