Kicking up the Dust Still Lying Around [*]

In the Weimar Republic, women were suddenly viewed differently by society: no longer just workers, housewives, and mothers, they were now also voters, consumers, and vehicles for advertising. Gesa Troja writes in the DHM blog about the new roles for women in the Weimar Republic – and the new commercial and political advertising strategies that accompanied these changes.

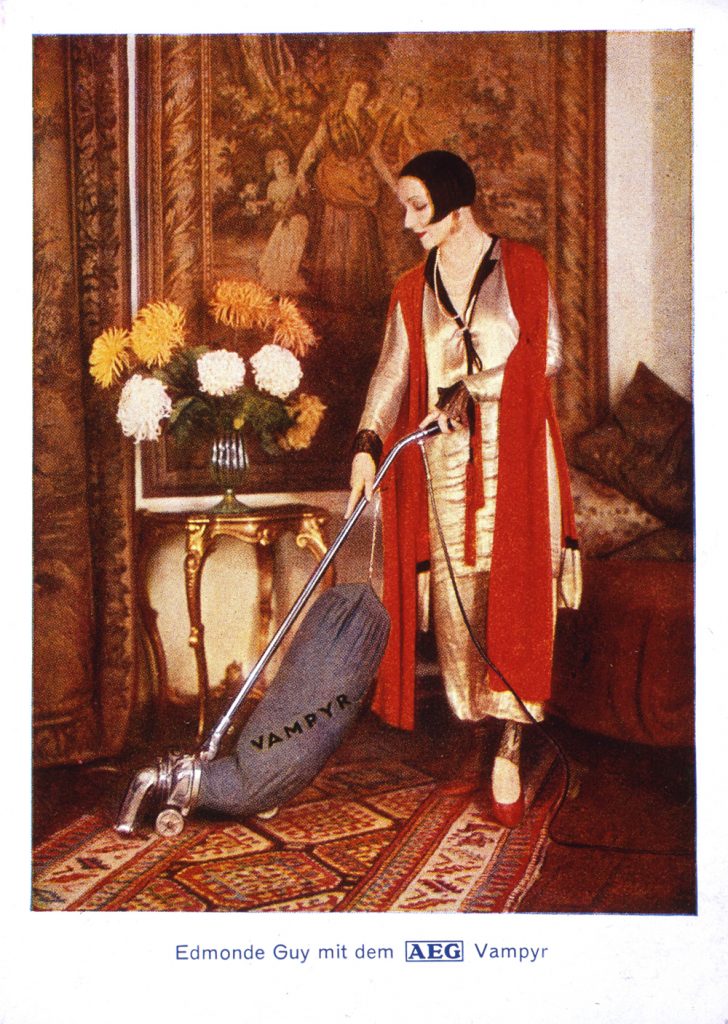

Vampires are creatures of the night. They sweep through the dreams and spaces of the living, eager to hungrily suck away their humanity. The same could perhaps be said of the two main attractions featured in the advertising postcard by the Allgemeine Elekricitätsgesellschaft (AEG) from 1929, which shows the company’s latest technical achievement: the ‘Vampyr’ vacuum cleaner, elegantly manoeuvred around a grand drawing room by Edmonde Guy, a famous actress and dancer who gained notoriety for her vampish persona. Powered by electricity, the AEG ‘Vampyr’ insatiably sucks up the scattered remnants of daily life from the thick weave of the rug. Edmonde Guy, on the other hand, is driven by a different force entirely – the power of seduction, spending night after night on stage gorging on the willpower of her male audiences at the revue. Unlike the woman and the appliance, the historicist-style interior of the drawing room setting looks anything but modern, and yet it is central to the sales pitch: adorning the wall behind the domesticated cabaret dancer is a tapestry, whose romanticized subject – a woman in what looks like Baroque costume, accompanied by her flute-playing husband and adorable child in a German woodland setting – radiates a family idyll. By adeptly using the visual conceit of a picture-in-a-picture, the AEG advertisement proclaims its message to men of the Weimar Republic: with technical appliances such as the AEG ‘Vampyr’, you can even get a woman like Edmonde Guy to start a family with and clear up your mess.

‘Her whole life seemed to revolve around the game of luxury’,[1] writes Monika Portenlänger in her account of the emancipated femme fatale, a figure from the 1920s that lent expression to the changed social circumstances of the Weimar Republic. You might think, then, that being a vamp would not lend itself to operating a vacuum cleaner. AEG saw things differently. The message underlying its advertisement: thanks to the company’s effective and luxurious household appliances, there was nothing to stop a woman in 1929 from being both a housewife and femme fatale at the same time. This approach effectively tacked the company’s advertising strategy to the expanding range of roles available to women in the Weimar Republic. No longer simply workers, housewives, and mothers, women were now being targeted by political parties, institutions, and companies as potential voters, consumers, and advertising vehicles. However, the new spaces in which women could enjoy their more varied social role continued to be defined by narrow boundaries set and policed by men. This is evident from the postcard advertising the AEG ‘Vampyr’, as it becomes clear (perhaps on a second or third viewing) that the space it depicts is – surprise, surprise – defined and dominated by men.

Edmonde Guy with the AEG Vampyr, advertising postcard by the company AEG for the vacuum cleaner Vampyr, around 1929 © DHM

Women as Voters and Politicians

Despite sexual equality being enshrined in the constitution, for most women their ‘new’ daily routine continued to be governed by patriarchal rules.

The women who glimpsed the AEG’s advertising postcard in 1929 could vote in elections, a hard-fought right that they had achieved ten years previously. On seeing the vacuum-cleaning actress, they may well have wondered how this domesticated femme fatale might have voted – if, indeed, she even made a cross on the ballot paper at the last election, or instead preferred to take care of the spider chrysanthemums in the living room. After more than 90 percent of the women entitled to vote participated in the 1919 elections to the National Assembly [the legislative body in Weimar charged with drawing up the new republic’s constitution], the number of women who exercised their right to vote in the years that followed dropped significantly.[2] This was possibly due to the lack of interest shown by many of the male parliamentarians in putting women’s concerns on the political agenda – themes they disparaged in comparison to other issues as mere ‘women’s stuff’.[3] Little could be done about this, even by the women elected in 1919 in order to help shape political decisions in the Weimar Republic. Women made up just 8.6 percent of the delegates voted to the National Assembly, and were even more underrepresented in the Reichstag following subsequent elections. There was also widespread disillusionment among female parliamentarians ‘with respect to the reluctance of male party representatives to put equal numbers of women on party lists and integrate them into politics’.[4] The work of Germany’s first professional female politicians also suffered because of parliamentary structures and processes that had become established in the years before women entered political life, with (for example) meetings frequently held at times that were impossible to reconcile with their duties as housewives and mothers. For even though women had achieved extensive political rights, life for the majority of them continued to be defined by patriarchal structures. Accordingly, it was felt that women’s first duty was to their homes and families, and even being an elected representative of the people did not exempt them from these pressing domestic obligations.

Women as Employees and Consumers

Although the constitution’s guarantees of gender equality extended to marriage, the German Civil Law Code (BGB) was extremely discriminatory towards married women.

If only they had owned a vacuum cleaner, this double burden would surely have been much easier for female parliamentarians and many other working women to bear! After all, in the Weimar Republic, female politicians were not the only women who in recent years had taken on paid employment in addition to their domestic responsibilities. Of course, there have always been women whose socio-economic circumstances left them no choice but to engage in wage labour; however, the rise of new educational opportunities and advanced communication technologies in the Weimar Republic opened up new career paths, enabling young and primarily unmarried women to help shape modern working life in offices throughout Germany’s major cities.[5] However, while this generation of ‘New Women’ now earned their own money, they were only paid about a third of what men got for the same work – and substantially less than would be needed to afford their own apartment with an elegant drawing room, Edmonde Guy’s stylish wardrobe, or even an AEG ‘Vampyr’.[6] Hence the AEG advertisement’s presentation of a vamp alongside a ‘Vampyr’ was not targeted at the purchasing power of working women, but that of wealthy husbands. The sort of man that, by the conventions of the day, even modern New Women would have been expected to snap up after a few years of going out to work. Once married, German civil law gave the husband legal authority over his wife’s life and fortune, even to the point of being able to forbid her from going out to work. By way of compensation, however, he might just treat her to a vacuum cleaner, which – of course! – she should try to operate to maximum seductive effect.[7]

Women as Advertising Medium and Feminine Ideal

The increasingly diverse range of social roles for women brought with them new dreams, but primarily new struggles.

While such urban female archetypes as the New Woman and vamp helped define the era, the roles themselves had little in common with the way most women lived in the 1920s. Instead, they were primarily a product of male fantasy and were quickly appropriated as advertising vehicles ‘by an expanding consumer and leisure industry that instrumentalized femininity and eroticism in hitherto unimaginable ways to sell its products’.[8] Nevertheless, these figures also became effective role models for women. Not only were women now supposed to take care of the household, bear and raise children, work and vote, they also had to be boyishly slim, with fashionable hair and skilfully applied make-up, in order then to cut the kind of vivacious figure associated with contemporary nightlife. This mainly meant one thing for women: huge amounts of effort. Indeed, quite often it was exhaustion, loneliness, and disillusionment that the thick layers of make-up served to conceal.[9] ‘In Weimar society, images of femininity were primarily constructed and legitimated via the male gaze’, explains the historian Lilja-Ruben Çaharnas Vowe, ‘to be then further consolidated by the world of consumerism and products, where the criteria for fulfilling the ideal were continually on display.’[10]

Edmonde Guy, the vacuum-cleaning showgirl from the AEG advertisement, puts on a show intended for the male gaze and embodies a male fantasy that continues to have currency to this day. Purchasing an AEG vacuum cleaner came with the promise for its (male) buyer of being able to subjugate a woman who ‘continually maintains her impenetrable froideur and never allows a man to feel as though he has made a definitive conquest’, as Portenlänger describes the figure of the 1920s vamp.[11] This subjugation fantasy directed at self-confident femininity is still around today, just as the AEG ‘Vampyr’ continues to suck up dust off the floors of German households. Only recently, the author Laurie Penny tweeted her outrage about the latest ‘trend’ in women’s subjugation: ‘“The new trophy wife in tech isn’t the hot young model. It’s the most brilliant, accomplished woman you can get to give up her career to have your kids” – a woman who works in tech told me this two years ago and it still haunts me #sexism.’[12]

If on 8 March we in Berlin are to celebrate the achievements that have brought about greater equality, then we should take a look back at the past as we set about really kicking up some of the dust that is still lying around. And (ideally) resist the urge to reach for an electrical household appliance to clear it up. We’ve still got a long way to go.

SOURCES

[*] The title refers to Margarete Stokowski’s description of contemporary feminist action. Even before, some of it was lying around. https://www.rowohlt.de/hardcover/margarete-stokowski-die-letzten-tage-des-patriarchats.html

[1] Monika Portenlänger: Kokettes Mädchen und mondäner Vamp. Die Darstellung der Frau auf Umschlagillustrationen und in Schlagertexten der 1920er und frühen 1930er Jahre, Marburg 2006, p. 18.

[2] See Ursula Büttner: Weimar. Die überforderte Republik 1918–1933, Bonn 2010, p. 252.

[3] See Lilja-Ruben Çaharnas Vowe: ‘1924: Wählerin and Konsumentin. Die ambivalente Doppelrolle der Frau in der Weimarer Republik.’ In: Ariadne 73–74 (2018), pp. 118–127, p. 118.

[4] See Marie Stritt: ‘Germany’ in: Jus suffragii, 6 (1919), p. 76, quoted in Marion Röwekamp: ‘Der graue Alltag des Stimmrechts. Die Zulassung von Frauen zu den juristischen Berufen als ein Schritt zu Citizenship-Rechten in der Weimarer Republik.’ In: Ariadne 73–74 (2018), pp. 90–99, p. 90.

[5] See Çaharnas Vowe: 1924: Wählerin und Konsumentin, p. 118.

[6] See Ursula Büttner: Weimar, p. 254.

[7] See Çaharnas Vowe: 1924: Wählerin und Konsumentin, p. 118.

[8] Portenlänger: Kokettes Mädchen und mondäner Vamp, p. 13.

[9] Julia Haungs and Anja Brauch: ‘Die “Neue Frau” der 20er’. In: SWR2 Wissen, https://www.swr.de/swr2/programm/sendungen/wissen/die-neue-frau/-/id=660374/did=21969824/nid=660374/1n5zp13/index.html (accessed 28 February 2019).

[10] Çaharnas Vowe: ‘1924: Wählerin und Konsumentin’, p. 125.

[11] Ortrud Gutjahr: ‘Lulu als Prinzip – Verführte und Verführerin in der Literatur um 1900’. In: Irmgard Roebing (ed.): Lulu, Lilith, Mona Lisa – Frauenbilder der Jahrhundertwende, Pfaffenweiler 1989, p. 57, quoted in Portenlänger: Kokettes Mädchen und mondäner Vamp, p. 18.

[12] Laurie Penny (@PennyRed), 23 February 2019, 10:55 a.m., Twitter.

© Private |

Gesa TrojanGesa Trojan is a researcher and educator who works in museum education at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. She is writing a doctoral thesis at the TU’s Center for Metropolitan Studies (Berlin) on the role played by everyday practices in processes of identity formation. She hates vacuuming and can be contacted via Twitter. |