Sheindi Ehrenwald’s Notes

Raphael Gross | 27 January 2020

The occupation of Hungary by German troops on 19 March 1944 marked the beginning of the Holocaust for the Hungarian Jewish population. Sheindi Ehrenwald, then 14 years old and living in the small town of Galánta, kept a diary from the day of the occupation, recording her experiences of intimidation, persecution, forced labour, and extermination. Under the heading Deported to Auschwitz, her notes are now on view in a curatorial intervention to our permanent exhibition. On 22 January, in a talk marking the unveiling of the display, Prof. Dr. Raphael Gross, President of the Deutsches Historisches Museum, explained the immediate context of her story.

The experiences which Sheindi Miller-Ehrenwald recorded in her diary were part of a wider context of cataclysmic historical events. By 1944, the Second World War, begun by Germany, was already in its fifth year. It took the Allies until 1942 to inflict their first significant defeats on Germany. More followed in 1943 and then, in September of that year, Italy capitulated, dealing a devastating blow to the network of European alliances with which Germany had surrounded itself. Hungary, with its autocratic and fundamentally pro-German government, had been one of Germany’s closest allies. In September 1943, however, the Hungarian government, alarmed at Italy’s surrender and not wishing to find itself on the losing side, established contact with the Allied powers and attempted to negotiate a separate peace. Germany received intelligence of these efforts. To prevent Hungary from changing sides and, at the same time, to secure better access to the country’s resources, Germany occupied the territory of its former ally. The German army marched into Hungary on 19 March 1944. This is the moment when Sheindi Ehrenwald’s diary begins.

Adolf Eichmann, head of Department 4 B 4 of the Reich Security Central Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt), arrived in Hungary almost as soon as German troops crossed the border, quickly followed by his special Hungarian task force. Straight away, he set about ensuring that the anti-Jewish measures already implemented in other countries were brought into immediate effect in Hungary too. The newly formed Hungarian government was dominated by anti-Semitic ministers, compliant with the will of the Nazi occupiers. By 29 March 1944, new legislation had already been passed, decreeing that from 5 April all Hungarian Jews must wear a yellow star. More anti-Jewish legislation swiftly followed – disclosure of financial status (enacted 21 March, enforced from mid-April) – restriction of freedom of movement (7 April) – food rationing (from 23 April) – creation of ghettos for Jews forcibly evicted from their homes (also from 7 April). Pressure from Germany and the German authorities met with eager support from Hungarian anti-Semites, who ensured that the legislation was introduced and brought into effect as quickly and comprehensively as possible. The Ministry of the Interior and the Hungarian police were particularly active in this regard. In an extremely short space of time – three weeks, to be precise – ghettos of various sizes had been set up throughout the country. Since there had been practically no time to prepare, empty factory sites and brickworks were often requisitioned for the purpose. Provisioning of the ghettos was very poor. There were no medicines, no sanitation, and very little food.

Sheindi Ehrenwald’s diary starts from the day of the occupation. At the very outset, she records her mother’s words: ‘The Germans have invaded […]’ and the reaction of one of her sisters: ‘That’s it for us.’ There was widespread international awareness by this time of German intentions with regard to the Jews. The implementation of the Holocaust, in other words, the complete annihilation of the Jewish people, had already begun in the summer of 1941 with the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Research is still ongoing to pinpoint exactly when and how this policy became official for all German authorities in the summer of 1941. It is clear, however, that by autumn 1941 at the latest, it was being actively pursued in all German-controlled territories. There was no longer any question of internal scruples or hesitations; the extent to which the plan would be implemented depended purely on political circumstances. Political circumstances were solely responsible for the ‘seemingly paradoxical fact that in the very countries which had been close to Nazi Germany from the start – Hungary, Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria, for example’1 – the Jews appeared to be in less danger than in countries which were directly occupied by German forces, such as Poland and the Netherlands. By the time anti-Jewish legislation was imposed in Hungary, most of the Jews from other countries – Poland, the Baltic states, and France, for example – had already been murdered. Many people therefore already knew what was to come in Hungary. Numerous Hungarian Jews, mainly in Budapest, returning conscripts from labour battalions, Hungarian soldiers returning from the Eastern front, and Jewish refugees from Poland and Slovakia, were spreading the information they had gathered about the mass exterminations. Sheindi Ehrenwald herself refers to the ‘terrible fate of the people in Slovakia’. Information also came from the BBC Hungarian Service. None of this, however, prevented the Germans from carrying out their plan to murder the Hungarian Jews. On 14 May 1944, deportations to Auschwitz from the Hungarian provinces began, with 12,000–14,000 people being deported every day.

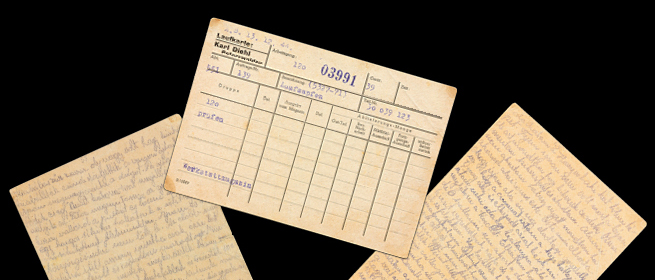

The space now devoted to the display ‘Deported to Auschwitz – Sheindi Ehrenwald’s Notes’ was previously occupied by the model of Auschwitz created by the Catholic Polish artist Mieczyslaw Stobierski. Stobierski made the model in Krakow in 1995 – 50 years after the liberation of Auschwitz. We decided to make this change to our permanent display because we felt it was important to allow a Jewish victim to speak to us in her own words. Sheindi Ehrenwald’s diary is a vivid reminder of those terrible crimes.

Reference

1 Dan Diner: Zeitenschwelle: Gegenwartsfragen an die Geschichte, 2010