The Godfather – Humboldt and the Invention of Photography

Anna Ahrens | 3 March 2020

In August 1839 the Parisian Academy of the Sciences revealed the secret of the first photographic process and presented it as a gift to humanity. One of the most important “godfathers” of daguerreotype, which was then offered as an “open source”, was Alexander von Humboldt, as the art historian Anna Ahrens explains in her blog in connection with the DHM exhibition “Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt”.

The Berlin art dealer Louis Sachse had been waiting for weeks for a delivery from Paris. On 6 September 1839 the very first cameras for Berlin finally arrived at his shop at Gendarmenmarkt. But in what condition!: all the bottles were broken, iodine and mercury had “turned everything brown”, the wooden stands and “silver plate cases” were ruined, the “cases with the chemicals [were] in a thousand pieces and no longer recognizable”.[i] It was a disaster. How could anyone send such precious contents so thoughtlessly on such a long trip? “That was packaging for a dairy wagon travelling from [the Paris suburb] St. Cloud to Paris, and even then you should be congratulated if it had arrived in one piece!” he wrote in an angry letter to the Giroux company – and he was not the only one who was disappointed: Alexander von Humboldt, who was “so urgently” waiting for his camera, “could not possibly believe that one could stick an unwrapped bottle of mercury in a crate!”[ii] Fortunately, both of them were well-acquainted with the Parisian art world as well as with the inventor of the first photographic process, Jacques Louis Mandé Daguerre. He had personally demonstrated his invention to Humboldt more than half a year earlier.

Rumour mill

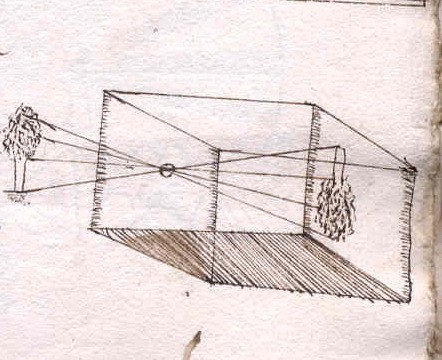

At the turn of the century 1838/1839 Humboldt visited Paris again. Wild rumours were circulating about Monsieur Daguerre, who was experimenting with images in his “chamber noir” [dark room]. It was said that by means of a mysterious process he could extract and fix the projections from a camera obscura – a darkened room or box, known since ancient times, that projects an image from the outside world through a small hole onto the inner wall on the opposite side.

Camera obscura. Pen and ink drawing from a handwritten manuscript of the Principa Optices from the 17th century

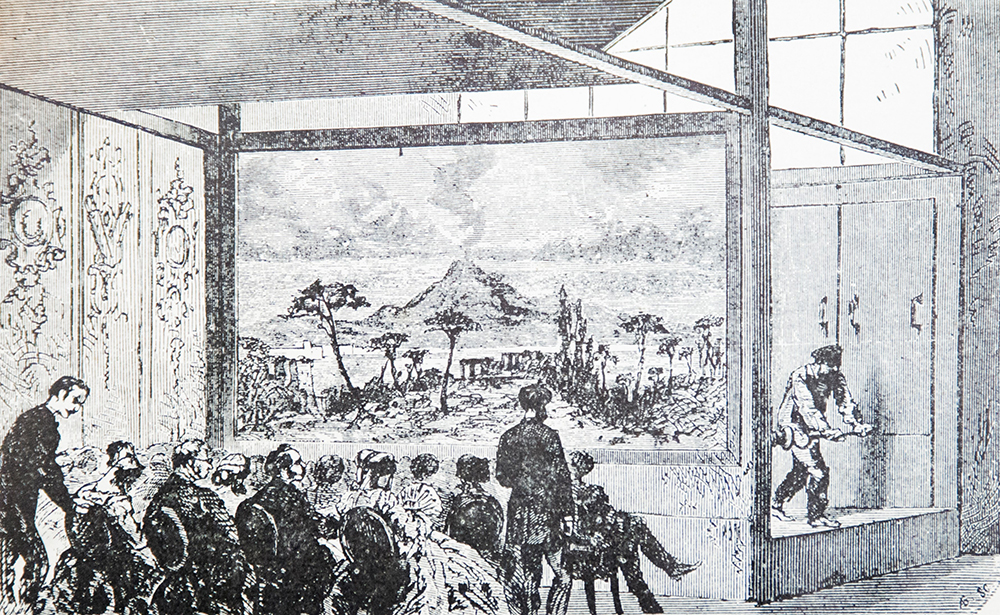

This, the media claimed, was the “art of the devil” and “blasphemy”, an illusion that Daguerre merely exploited as a new business model.[iii] For more than 25 years Daguerre had been running the Diorama in Paris, a darkened theatre in which huge painted panoramas could give the appearance of day or night by alternating the lighting, and could even seem to show movement.

Daguerre’s Diorama, presentation of a view of Mount Vesuvius, woodcut, around 1825

The popular attraction had burned down in the summer of 1838. However, Daguerre had long since been concentrating on his photographic process, which, with no false modesty, he named Daguerreotype.[iv]

Replica of Daguerre’s first camera from the House of Giroux, Paris 1839 © Deutsches Technikmuseum, Berlin, Coleccionando Camaras, https://www.flickr.com/photos/coleccionandocamaras/7236721090/

It was reported that in 1838 he packed his carriage full of equipment and travelled throughout Paris photographing monuments and public buildings.[v] He drummed up attention about his invention in order to either sell individual shares for 1000 francs apiece or to sell the exclusive rights to it for 200,000 francs. But the general skepsis toward the former Diorama owner was evidently still too great.

A secret meeting

“Finally,” wrote Daguerre on 2 January 1839, he had met with Arago.[vi] François Arago was the director of the Paris observatory, permanent secretary of the Academy of the Sciences and politically active as a republican deputy. The astronomer and physicist was, one could say, “almost” as famous as Humboldt. They had been close friends for thirty years.[vii] Arago brought in the third member of this alliance, the physicist and mathematician Jean-Baptiste Biot.[viii] This trio of prominent researchers immediately understood the significance of Daguerre’s discovery. Arago took over the mandate. His plan: to sell the procedure exclusively to the French government for the desired 200,000 francs. Already on 6 January 1839 he launched a press release in the Gazette de France which announced a “revolution” for the sciences and arts.[ix] On 7 January 1839 Arago presented the invention in the Academy of the Sciences, the “authenticity” of which Humboldt and Biot had also confirmed.[x]

Why was it so important for Arago to have his Berlin friend with him at the meeting? Humboldt was already a person of world renown, a widely read author and skilled diplomat who occupied himself not only with his outstanding scientific research, but also with social and artistic questions. That was a decisive factor, because Daguerre had personally shown his visitors several times how the images came about, but he had not – “unfortunately!”, said Humboldt – revealed his secret.[xi] Two letters that Humboldt wrote in February 1839 are among the earliest and most important literary testimonies concerning the course of the publication of photography. One is addressed to Duchess Friederike von Anhalt-Dessau,[xii] the other to Carl Gustav Carus from Dresden, the important physician, scientist and artist friend of Caspar David Friedrich’s.[xiii] These letters are key documents for the understanding and progress of a previously unparalleled media campaign that catapulted the invention of photography with a bang on 19 August 1839 into the consciousness of the world public.

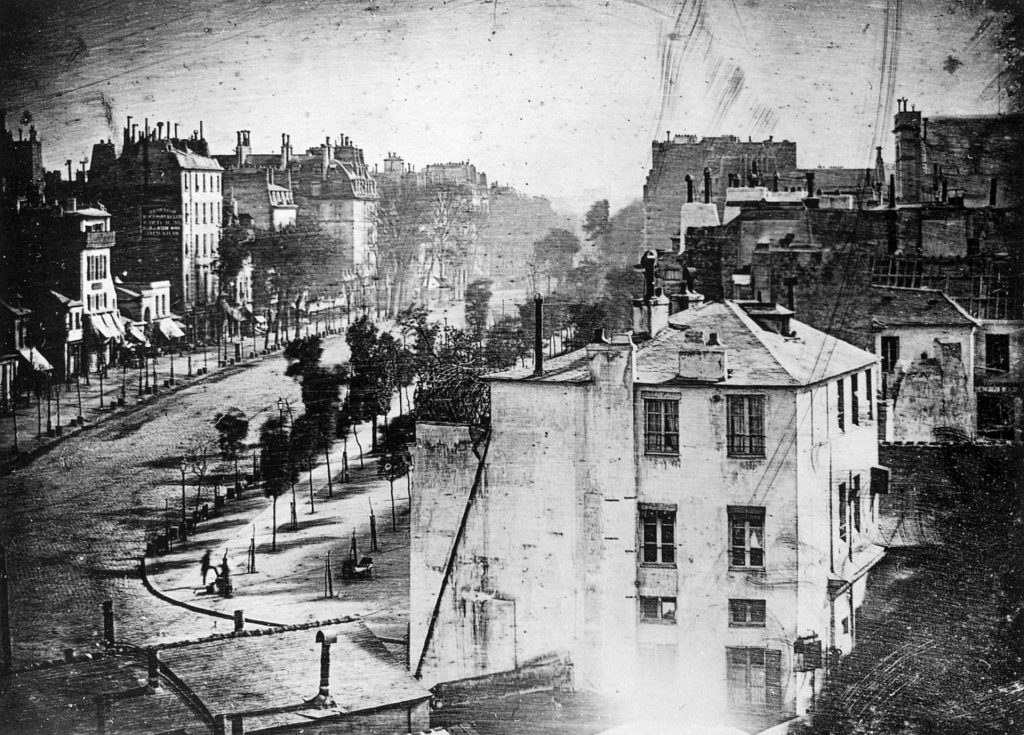

Understanding and imagination

Humboldt was enthusiastic about Daguerre’s pictures from the very first moment: they “unremittingly inspired the understanding and the imagination.”[xiv] The photocarrier – a copper plate coated with a thin layer of silver – became iridescent brown-grey-colourful depending on the light situation. He presented his photos as artworks “under glass and frame”. They showed city views of Paris and still lifes.[xv]

View of a street in Paris (Boulevard du Temple), Daguerreotype by Louis Daguerre, taken from the window of his studio, 1838

![Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, L´Atélier de l´artiste [The Artist’s Studio], Daguerreotype, 1837](/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Abb-5--1024x745.jpg)

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, L´Atélier de l´artiste [The Artist’s Studio], Daguerreotype, 1837

Coalitions

The rumours, sensational headlines and claims of priorities after Arago’s press release caused a huge stir everywhere. “The same questions are posed to me forty times a day. The announcement of having seen how the image comes about and how it is generated without difficulty – that is the decisive factor,” confirmed Humboldt in a letter to his friend at the end of April 1839.[xxiii] In February 1839 he had already assured Duchess Friederike and Carl Gustav Carus: “No one in the Parisian world except the inventor knows more about it than we do.”[xxiv] And it is exactly at this point that the matter again becomes exciting.

For already in January 1839 Humboldt, Arago and Biot had each received an identical letter from the gentleman scholar Henry Fox Talbot of London, in which he submitted well-founded priority claims for the invention.[xxv] Officially the three scientists rejected Talbot’s claims. But Humboldt confided to the duchess: “I am very glad that the letter [from Talbot] did not reach me in Paris, because it may cause an unpleasant dispute about priorities” – and added: “How should one explain that the honourable Englishman has kept such an invention secret, like the Pope from the cardinals?”[xxvi] Humboldt could not understand how anyone could hold back the knowledge of a discovery so important for humanity. It was incompatible with his liberal view of the world. He did not, however, basically question the achievements of his British colleague. Always the diplomat, he sent Duchess Friederike both the “little letter of Mr Talbot (a lovely old name)” as well as “an announcement of Daguerre’s”, which “is also a rarity.”[xxvii] He let the duchess form her own opinion. If the adversaries should “fight against each other and become agitated”, however, he would be obliged to take an official position.[xxviii] Humboldt must have foreseen that he would be faced with this dilemma. On 5 March 1839, barely four weeks later, he addressed a private letter to his English colleague Talbot. His formulations are full of ambiguities. Humboldt speaks of a time “in which coalitions were the order of the day.”[xxix] The word “coalitions” is the only one he underlined, as if he wanted to be sure that the London scholar would understand how to interpret his statement: Humboldt had long since formed a coalition with Arago and Daguerre, which he would honour.

Fin

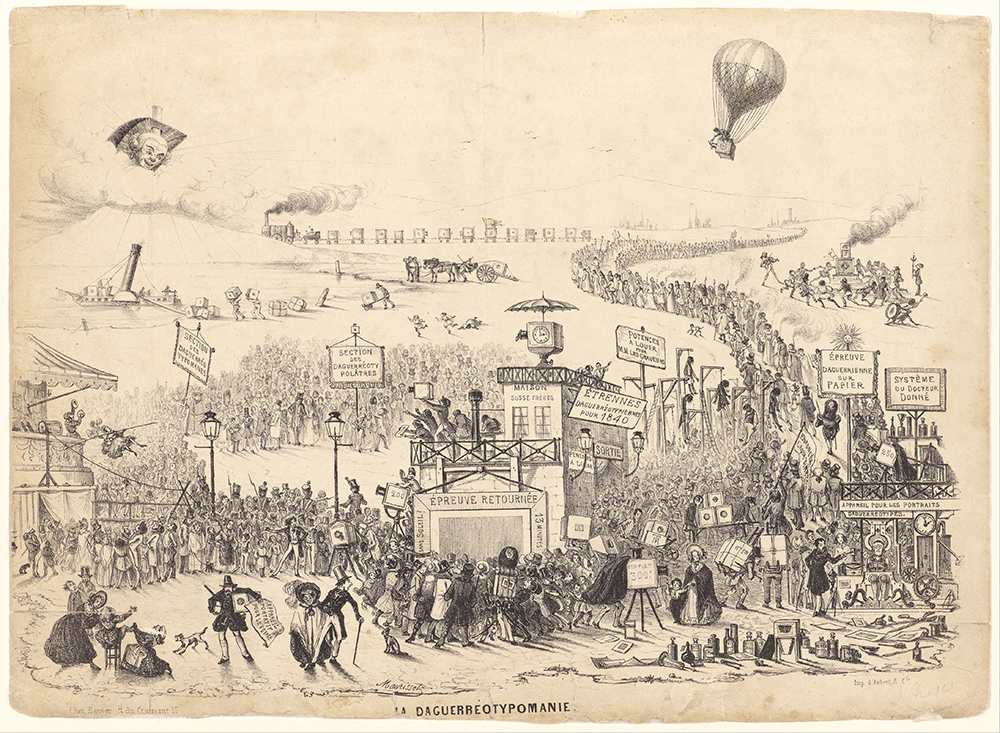

The story has a happy end, as we know, for they all got their due. Humboldt stood by his friend Arago,[xxx] who saw to it that the government bought Daguerre’s invention and presented it as a gift to humanity on 19 August 1839. It was an ingenious coup: with the publication of photography as an “open source”, as we would now call it, the new medium celebrated the democratic potential of the modern age. From this time on there existed a world of images before August 1839 and a different one thereafter.

Theodore Maurisset, Daguerreotypomania, December 1839, Lithograph

Talbot also got his due: he became the inventor of photography as a negative process on paper, which won out in the end. In 1844, the same year in which Talbot compiled his famous photobook The Pencil of Nature, he also sent Humboldt a photo album with 22 photographs – it is the first photobook of the world.[xxxi]

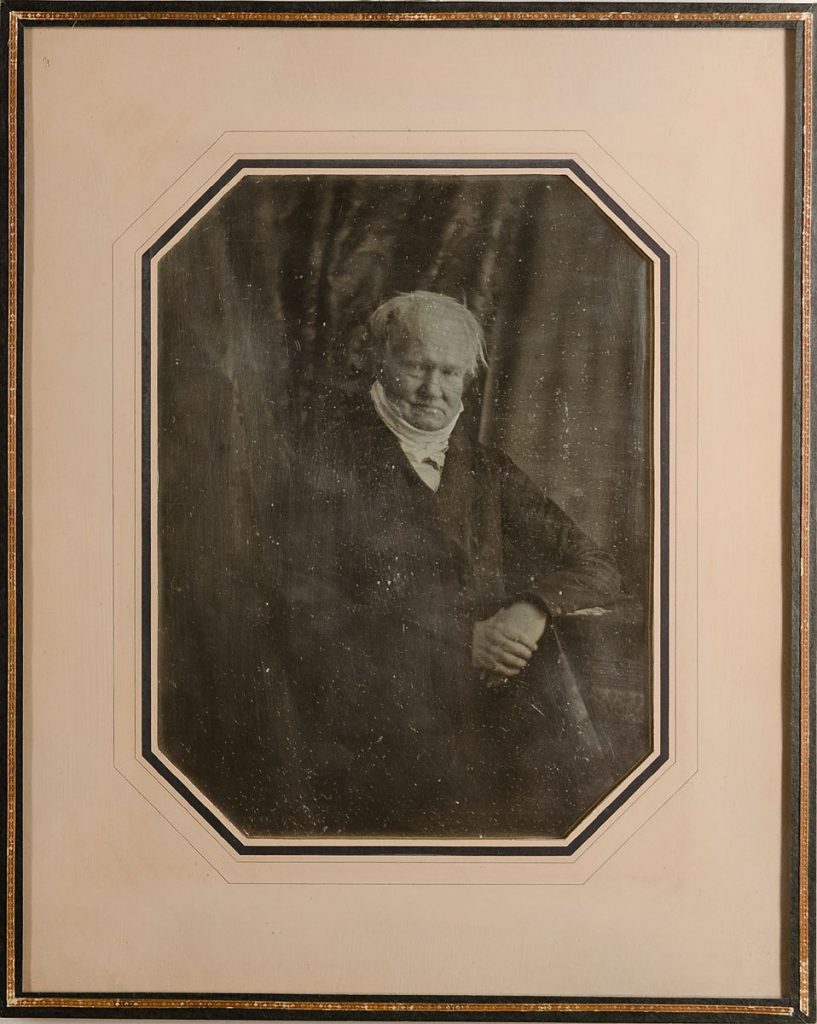

Herrmann Biow, Alexander von Humboldt, 1847, Daguerreotype

And whatever happened with Humboldt’s first camera? “With great effort” Louis Sachse succeeded in getting the French cameras to work. On 20 September 1839 he presented his own first pictures in his shop: “a picturesquely draped room” and a view of Jägerstrasse in the direction of Gendarmenmarkt.[xxxii] Humboldt himself probably never in his life pressed a shutter button. But he had portraits of himself made with a camera and used the image maker from that time on for his extensive research.

Sources

[i] Louis Friedrich Sachse to the company Giroux & Cie. in Paris, 6 September 1839; cit. in Anna Ahrens, Der Pionier. Wie Louis Sachse in Berlin den Kunstmarkt erfand, Cologne/Weimar/Vienna 2017, p. 231. On the Giroux company, which produced and sent the first cameras, see p. 226ff. For the introduction of photography in Berlin cf. pp. 217-276. Also Anna Ahrens, “Niemand in der Pariser Welt weiß mehr als wir davon”. Alexander von Humboldt und die Geburtsstunde der Fotografie, in: David Blankenstein, Ulrike Leitner, Ulrich Pläßler und Bénédicte Savoy (eds.), “Mein zweites Vaterland”. Alexander von Humboldt und Frankreich, Berlin 2015, pp. 261-277.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Cf. Walter Benjamin, Kleine Geschichte der Fotografie (1931), in: Texte zur Theorie der Fotografie, ed. by Bernhard Stiegler, Stuttgart 2010, pp. 248-269, here p. 249; Ahrens 2017, p. 228ff.

[iv] Daguerre’s former business partner Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833), inventor of heliography, had already undertaken decisive attempts in the mid-1820s. After the latter’s death his nephew Isidore Niépce took over the contract which Daguerre had renewed in his favour after his successful results with shortened exposure times (from September 1837).

[v] Cf. Helmut Gernsheim, Geschichte der Fotografie. Die ersten hundert Jahre, Berlin 1983, p. 58.

[vi] Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre to Isidore Niépce, 2 January 1839, printed in full in Steffen Siegel (ed.), Neues Licht. Daguerre, Talbot und die Veröffentlichung der Fotografie im Jahr 1839, Paderborn 2014, p. 41.

[vii] François Arago (1786-1853). Humboldt calls Arago his “radical! friend” and at the same time one of the “kindest people on earth”. Cf. Alexander von Humboldt to Herzogin Friederike von Anhalt-Dessau, 7 February 1839, printed in full in: Siegel 2014, pp. 78-79, here p. 79. On Arago’s importance in the course of the introduction of photography cf. also Anne McCauley, Arago, l´invention de la photographie et la politique, in: Études photographiques, 2 (May 1997), pp. 6-34.

[viii] Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862).

[ix] Henri Gaucheraud, Die Schönen Künste. Neue Entdeckung, in: La Gazette de France, 6 January 1839, p. 1; German translation in: Siegel 2014, pp. 49-51.

[x] Ibid. and Dominique François Arago, The fixation of images that are formed in the focus of a camera obscura, protocol of the session of 7 January 1839 in the Academy of the Sciences in Paris, published in: Comptes rendus hebdomanaires des sciences de l´Académie des Sciences 8 (1839), pp. 4-6; German translation in: Siegel 2014, pp. 51-54.

[xi] Alexander von Humboldt to Herzogin Friederike von Anhalt-Dessau, 7 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 78.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Alexander von Humboldt to Carl Gustav Carus, 25 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 85ff.

[xiv] Alexander von Humboldt to Herzogin Friederike von Anhalt-Dessau, 7 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 78.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Alexander von Humboldt to Carl Gustav Carus, 25 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 85.

[xvii] Henri Gaucheraud, Press release from January 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 50.

[xviii] Dominique François Arago, Protocol of the session in the Academy of the Sciences in Paris 1839, cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 53.

[xix] Alexander von Humboldt to Carl Gustav Carus, 25 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 86.

[xx] Ibid. and Petra Werner, Himmel und Erde. Alexander von Humboldt und sein Kosmos. Berlin 2004, p. 126.

[xxi] Alexander von Humboldt to Herzogin Friederike von Anhalt-Dessau, 7 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 79.

[xxii] Alexander von Humboldt to Carl Gustav Carus, 25 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 86.

[xxiii] Alexander von Humboldt to François Arago, 25 April 1839, cit. in: Hanno Beck, Alexander von Humboldt. Förderer der frühen Photographie, in: Silber und Salz. Zur Frühzeit der Photographie im deutschen Sprachraum (1839-1860). Catalogue manual for the 150th anniversary of the Agfa-Foto-Historama, Cologne, Joseph-Haubruch-Kunsthalle, Munich, Stadtmuseum and Hamburg, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, ed. by Bodo von Dewitz and Reinhard Matz, Cologne 1989, pp. 40-59, here p. 43.

[xxiv] Alexander von Humboldt to Herzogin Friederike von Anhalt-Dessau, 7 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 78, and Alexander von Humboldt to Carl Gustav Carus, 25 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 85.

[xxv] Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877), English photo pioneer.

[xxvi] Alexander von Humboldt to Herzogin Friederike von Anhalt-Dessau, 7 February 1839; cit. in: Siegel 2014, p. 79.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Humboldt’s letter to Talbot is printed in full in: Beck 1989, pp. 40-59, here p. 53.

[xxx] Alexander von Humboldt to François Arago, 25 April 1839; cit. in: Beck 1989, p. 43.

[xxxi] On the occasion of the 250th anniversary of Humboldt’s birth, the Museum Ludwig presented from 13 October 2018 to 10 February 2019 under the title “Alexander von Humboldt, die Fotografie und sein Erbe” a successful exhibition on this topic from the museum’s own photo collection, including Talbot’s album that he gave to Humboldt in 1844.

[xxxii] Ahrens 2017, p. 234.

© Privat |

Dr. Anna AhrensDoctorate in art history (“Der Pionier. Wie Louis Sachse in Berlin den Kunstmarkt erfand”, 2013/17), since 2014/18 staff member and head of the 19th century art department at the auction house Grisebach, Berlin. Previously research associate at research projects and exhibitions on 19th century art in Berlin and Lübeck, and lecturer at universities in Berlin, Cologne and Marburg. |