Witness of the Holocaust: Sheindi Ehrenwald’s Notes

Thomas Jander | 29 July 2020

Some 6 million people were murdered in the Holocaust. In addition to this human devastation, the Holocaust left in its wake many personal effects stolen from those sent to their deaths. Often, all that’s left behind are the names on suitcases and other items that couldn’t be re-used or sent elsewhere. Having also been robbed of their history, such objects can today only serve as mute witnesses of their former owners. Writing for the DHM blog, Thomas Jander, head of the Documents Collection and curator of the exhibition “Deported to Auschwitz – Sheindi Ehrenwald’s Notes”, chronicles the example of Sheindi Miller-Ehrenwald, a Hungarian Jew whose diary notes have become ‘speaking’ witnesses of this unparalleled crime in human history.

Hidden, Smuggled, and Buried

Had it been up to the perpetrators, the crimes of the Holocaust would have disappeared from history as something ‘never mentioned and never to be mentioned’, to cite the infamous ‘Posen speech’ given by Heinrich Himmler to an audience of SS Gruppenführer in 1943. This approach had already been adopted more or less consistently for some time in the SS’s day-to-day internal correspondence. Such crimes as slave labour, deportation, and murder were obscured, disavowed, and hushed up in terms like ‘work assignment’, ‘evacuation’, and ‘special treatment’.

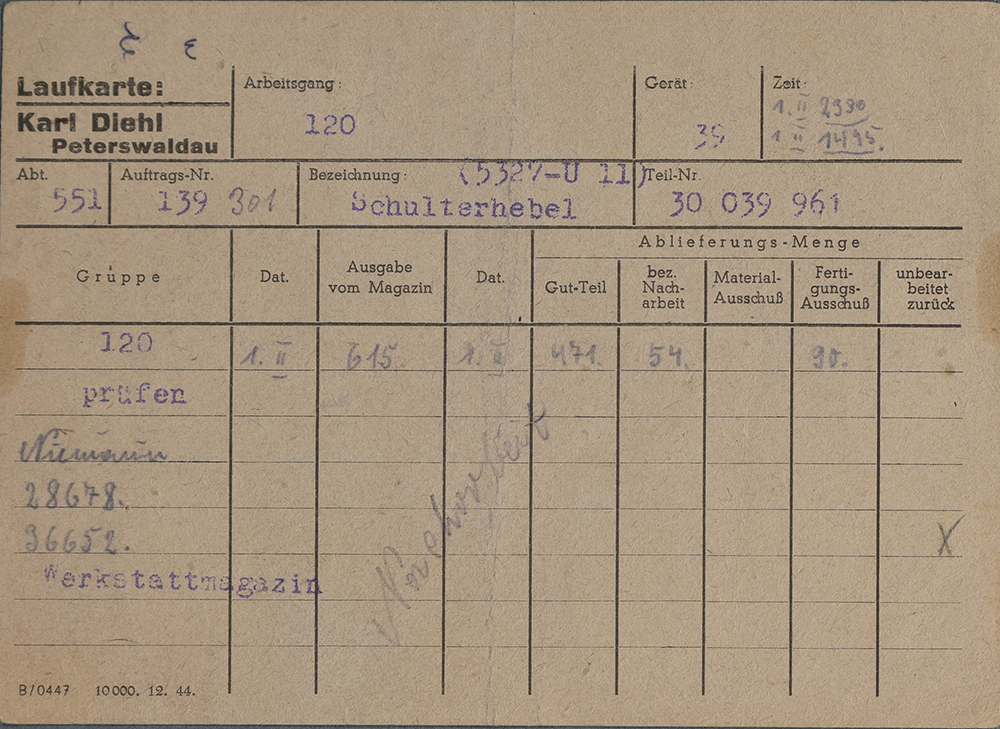

Index card of the Diehl company, Factory Peterswaldau, for the documentation of time fuses, 1944/45 © Private collection Sheindi Miller-Ehrenwald, Jerusalem

The aim was to ensure that the Holocaust’s victims could themselves never bear witness to what had been done to them – and yet bear witness they did. In hiding places, ghettos, and even concentration camps, the persecuted and incarcerated recorded what they and others had to live through and endure. Written accounts – from secret messages through to diaries – were hidden, smuggled, and buried so that their stories could be heard across space and/or time. These documents came to be particularly valuable sources, as they give extremely compelling accounts of an event that was otherwise almost invariably coded in the obscuring and distorting administrative language of the Nazis.

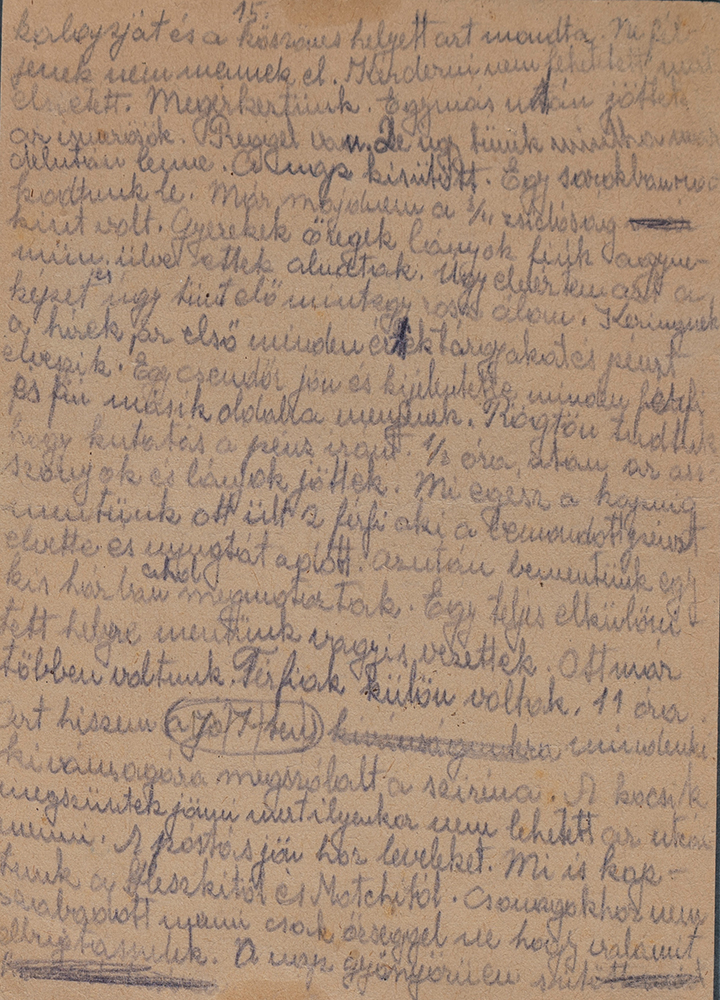

Back side of the index card with notes by Sheindi Ehrenwald taken from her diary, 1944/45 © Private collection Sheindi Miller-Ehrenwald, Jerusalem

Diary from Hungary

One such testimony is the central object of the exhibition Deported to Auschwitz – Sheindi Ehrenwald’s Notes, which we are showing as part of our permanent exhibition. The diary – or, rather, notes based on the diary – form the core of a highly personal and yet simultaneously collective history: the history of the destruction of the Ehrenwald family, and that of Hungary’s Jews.

Portrait of members from the Ehrenwald family, in front Sheindi’s father Lipót Ehrenwald, around 1935 © Private collection Sheindi Miller-Ehrenwald, Jerusalem

When Sheindi Ehrenwald, the sixth child of the wine merchant Lipot Ehrenwald and his wife Cilly, was about 14 ½ years of age, the Wehrmacht invaded her home country of Hungary (which had in fact been allied with Nazi Germany). Fearing that the authoritarian-fascist state headed by the regent Miklós Horthy might follow Italy’s example and turn against its former ally, Adolf Hitler ordered the occupation of Hungary for 19 March 1944.

This was the day on which Sheindi began her diary. Her family was living at the time in the small town of Galánta close to the Slovakian border, where they formed part of a large and thriving Jewish community. News of the German occupation also came as a shock for the Ehrenwalds: ‘That’s it for us’, as Sheindi wrote in her diary, recording the words of her younger sister. It’s unclear whether the comment was informed by specific information about the Holocaust and death camps then circulating in Hungary (whose Jewish population had so far been largely spared), or whether it expressed a vaguer sense of looming threat from Nazi Germany more generally. Either way, following on the heels of the Wehrmacht was an SS Sonderkommando (special task force) headed by Adolf Eichmann and sent with a very specific mission: to organize the persecution and subsequent deportation of Jews living in Hungarian territory.

In the following weeks, Sheindi, her siblings, parents, and grandparents endured an unrelenting succession of traumatic events. They had to bear the mark and stigma of the yellow star that all Jews were forced to wear by order of anti-Semitic legislation introduced by the newly installed Hungarian regime. They were then forced out of their home and into a local ghetto, before being transported to an assembly camp. Sheindi’s diary records this tragedy from the perspective of a teenager, who closely observes the world around her in which she experiences suffering, anger, and sadness – yet without knowing or sensing the immensity of the catastrophe about to befall her.

Deportation of inmates from the Körmend ghetto (Hungary) towards Auschwitz-Birkenau, 19 June 1944 © Holokauszt Emlékközpont, Budapest

Working closely with Edmund Veesenmayer (the German Reich’s plenipotentiary in Hungary) and Eichmann’s Sonderkommando, the Hungarian Gendarmerie took less than two months to force more than 437,000 Jews initially into over 50 hastily improvised ghetto-like assembly camps, from where they were then deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp. Three quarters of the Hungarian Jews who arrived there in the period up to July 1944 faced an appalling death. The majority of arrivals were classified by the SS as ‘incapable of work’ and sent directly to the gas chambers.

A Vital Memory

We don’t know exactly how Sheindi survived the two months in the women’s camp at Birkenau, but she and some 100,000 other Jewish prisoners were requisitioned by German companies for forced labour. This meant she was able to escape the camp where she would otherwise have faced almost certain death. Amid the chaos of the camp, her diary remained undiscovered. Sheindi was able to smuggle the pages (which had been severely damaged during her time at Birkenau) to the next concentration camp, a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen complex. What’s more, she managed to copy her diary secretly onto index cards from the armaments factory where she had been put to work.

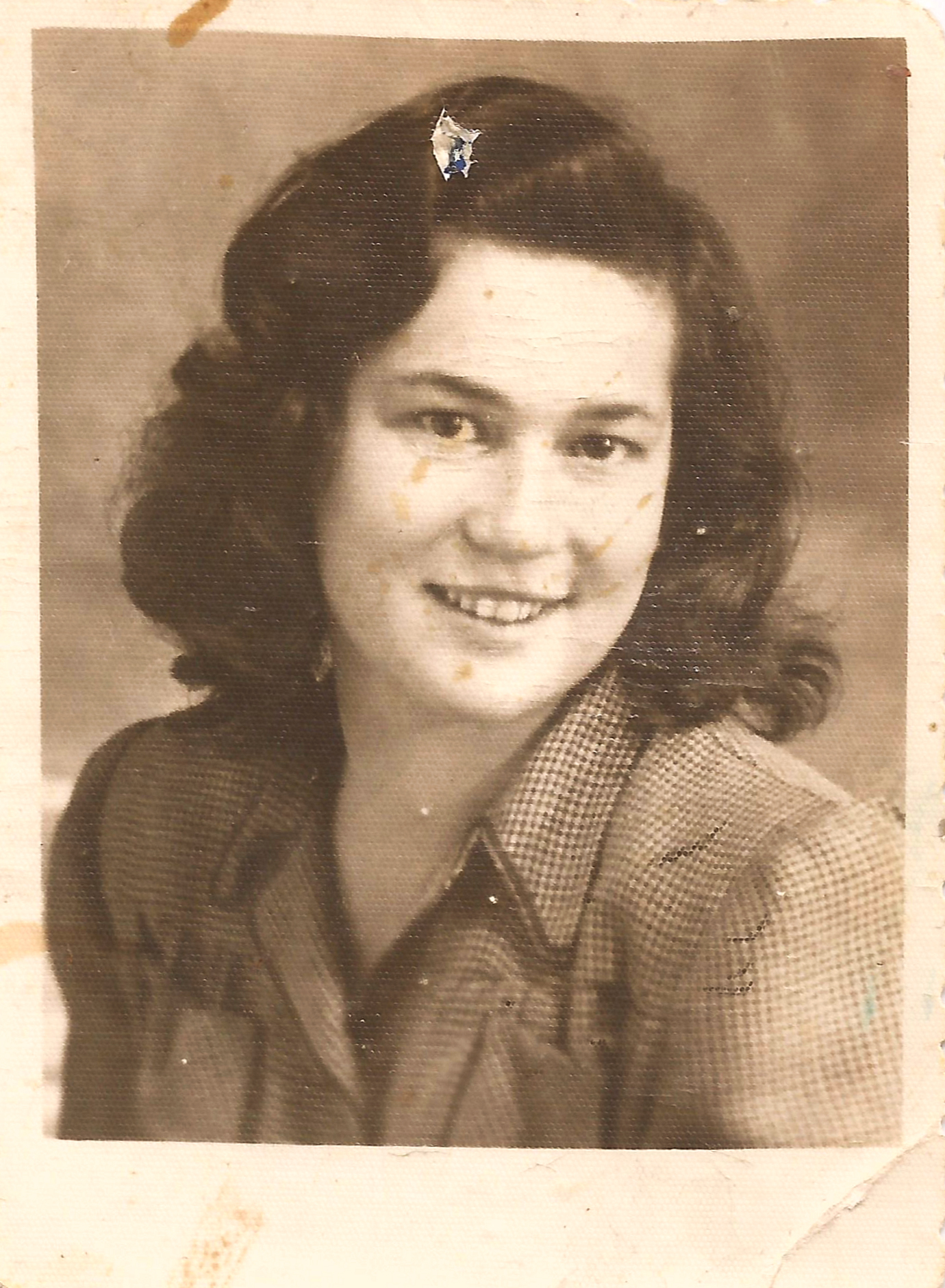

Passport photograph of Sheindi Ehrenwald (now: Sheindi Miller-Ehrenwald), 1947 © Private collection Sheindi Miller-Ehrenwald, Jerusalem

Sheindi had hoped that by writing these notes she could preserve her memories for her parents. However, only she and her sister Yitti returned home in 1945: all the other members of the Ehrenwald family had been murdered. The diary notes continue to preserve a vital memory. In our exhibition, which we had the privilege of opening with Sheindi Miller-Ehrenwald in attendance on 22 January this year, we are showing these pages for the first time to the general public. Displaying Sheindi’s notes is an opportunity for us to put greater emphasis in our permanent exhibition on the perspective of the Holocaust’s victims.