Report from Exile

Ayham Majid Agha | 12 May 2021

How many times a day do we remember that we are in exile?

We are not counting, because we face it in our gray hair and wrinkles whenever we see our selves in a picture or a mirror.

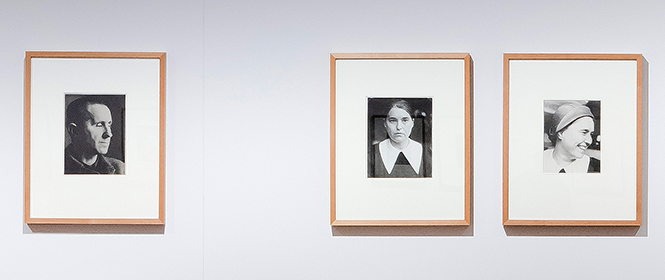

In Stein’s photography, exile is not apparent in a certain place or in the distance of other countries, rather: it’s apparent in the character’s faces, in their eyes, hearts and bodies awaiting the news of what has become of their homeland.

In the exhibition “Report from Exile”, I had a question: Which was the harshest, the Parisian or the American exile?

The portraits taken in Paris reminded me of our faces when we headed to the first stops in our Syrian exile near the borders of our country. Faces that still carry fear and panic. We were terrified when someone was staring at us. We couldn’t remember at the time that looking at the other was a means of communication. We were unable to cope fast, because our hearts knew that Damascus was less than an hour away. Most of us grew up ten years in a year.

Did the characters in Stein’s portraits have that fear that danger was still near them, and that they had hope of returning, perhaps tomorrow?

To be exiled on the borders of your homeland burdens the heart, and paradoxically gives you a sense of security and the opposite.

Brecht in Paris in the year of 1935 looks older than the Brecht in New York in the year of 1943. The same goes for Anna Sieghers, Hannah Arendt and Alfred Kantorowicz; their eyes were open windows to the story that trampled their days and wounded their souls.

Do distances isolate our feelings, not just our bodies?

Does it make the news from the homeland less harmful and impactful?

Exile is encapsulated by all these people, their stories, their diaries, their losses, and their destinies.

Fred Stein’s photos expose the characters’ link to their homeland and retrace them back there. He ties together the vocabulary of what it means to be in exile not by the thread itself but by the unique details intricately sown into each shot. This opens up a blank page the size of the earth, impelling you to fill it with writings, drawings and pictures about your own country.

I’m not falling into the trap of a comparison, at least I hope so very much, but rather in an attempt to understand the mechanisms of writing and documenting during and after those forced experiences.

Working with and in the German Historical Museum is an opportunity to investigate various artistic documentation and narration mechanisms, to look and to point at events and their narratives and to hope that one day we’ll be able to apply them on our exile as a historical event.

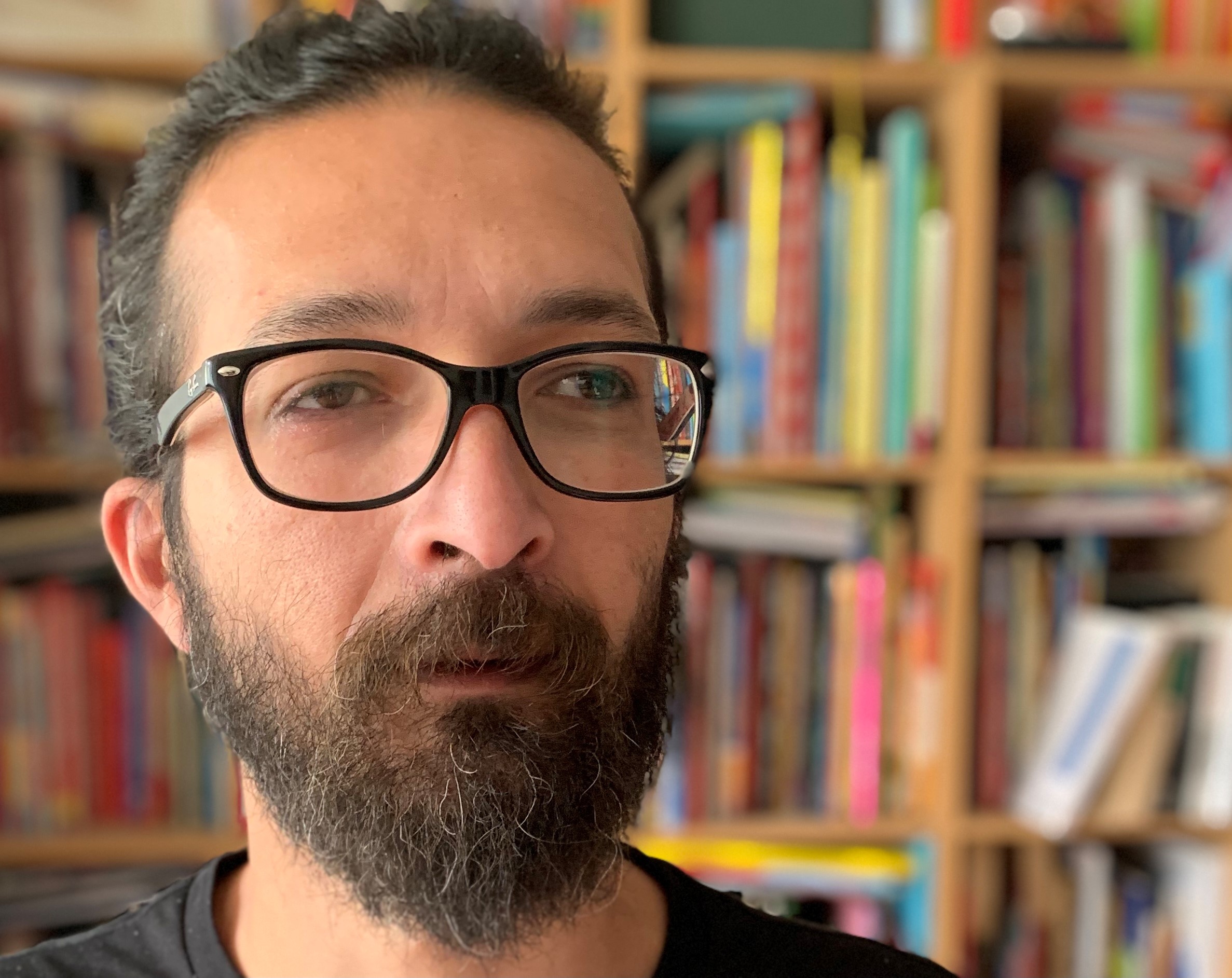

© Private |

Ayham Majid AghaAyham Majid Agha is an actor, writer and director. He was born in Syria and graduated from the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts in Damascus, where he was a junior professor from 2006 to 2012. He was a co-founder and member of the Theatre Studio, which performed interactive theatre projects in Syrian villages. He had numerous engagements at theatres in Damascus, Manchester, Amman, Beirut, Cairo, Seoul, Paris, Lyon, Munich and Hanover. He lives in Germany since 2013 and worked at the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin, most recently as senior director and co-founder of the Exile Ensemble. His play “Skeleton of an Elephant in the Desert” was awarded the Young Theatre Critics Award at the Radikal Jung festival in 2018. |