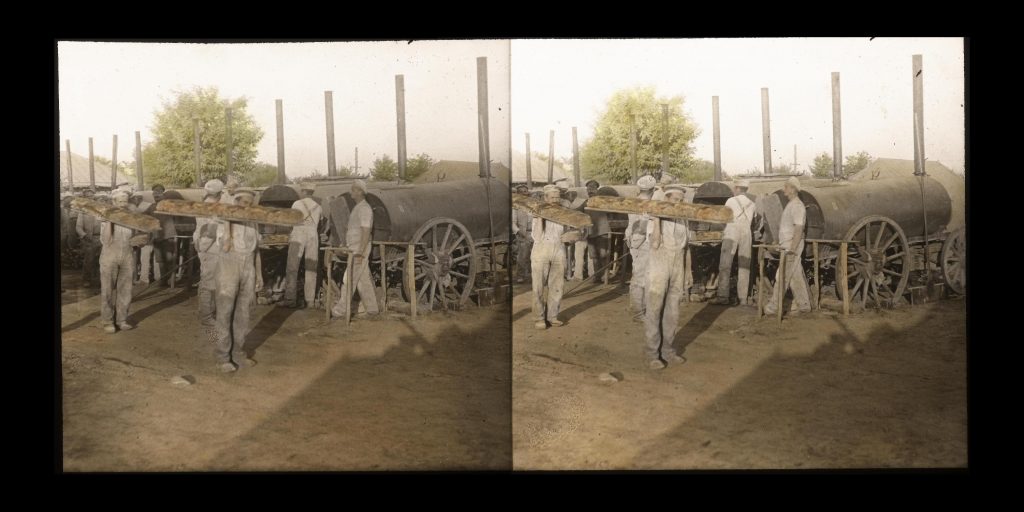

A “Turkish Bakery Run with German Matériel and German Methods.”

An Army Baker Recalls His Posting to Romania in WWI.

Nico Geisen | 1 September 2022

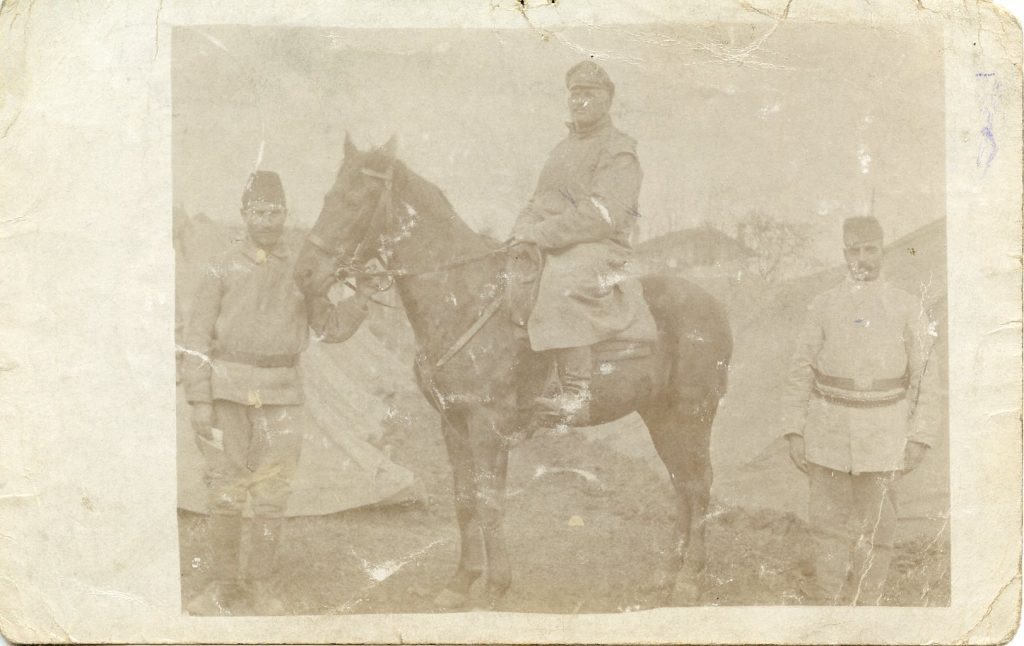

During World War I, the exchange of military supplies and equipment between alliance partners was already a standard way of providing mutual support. For example, German military staff were posted to a Turkish division for the Central Powers’ offensive against the Kingdom of Romania. A German army baker from WWI left behind documents that give some insight into the difficulties that this type of exchange could entail, as Nico Geisen, a curatorial trainee at the collection, describes in this article.

On 28th September 1916, Richard Gorgas, a master baker and newly appointed acting field baker, received his orders to ship out and join a Turkish unit. Once there, as he recorded in a notebook describing his “time with the Turks,” he was to set up “a Turkish bakery run with German matériel and German methods.” No sooner had he arrived than he realized he lacked one crucial ability: he spoke no Turkish whatsoever, the only language understood in his field bakery unit. Even reporting to his Turkish superior officer proved difficult. He had help from a man named Hassan, assigned to him as an interpreter, but he still often communicated with his bakery comrades in sign language alone. Even his own notes on Turkish phonetics were of limited assistance.

On 17th August 1916, the Kingdom of Romania joined the Allied powers. As a result, by September, all the Central Powers had declared war on the kingdom.[1] Under Germany’s overall command, the Central Powers’ plan was for Bulgarian and Turkish troops to attack from the south, across the Danube. They would be supported by German supplies and equipment, including, for example, Gorgas’ field bakery.

Just a few days after Gorgas arrived in Bulgaria, the troops began to advance on Romania. There was scarcely time for the bakers to be instructed in their new jobs. Gorgas attempted to provide non-verbal training for the men under his command, but by the first inspection he had no satisfactory results to show. In letters home to his family, he described the verdict of the inspecting lieutenant: “[He] did not really seem to understand how the German ovens worked and regarded them with great scepticism and I had considerable trouble diverting his thoughts to other matters; he went away shaking his head.”

Most of the troops advanced on foot. Transporting the bakery unit – consisting of twelve ovens, twelve baggage waggons, a supply waggon, a field forge, and field kitchen – was therefore often stop-and-go, despite the fact that all the waggons were supplied with at least two draught horses. Chaos ensued, for example, on the steep road leading down to the Danube crossing at Svishtov. Gorgas summarized what happened as follows: “1 waggon overturned, one ran into another at a garden wall, taking a railing with it, two waggons took wrong turnings, heading off in opposite directions, and meanwhile the rain came down in torrents.” Most of the marching was done in the morning, the evening, or even at night, so that the day could be spent working. When the unit was billeted at a new location, operations were divided up between three shifts, each consisting of 23 bakers and head bakers, so that around 8000 loaves (sometimes as many as 13,000) could be baked per day. One field bakery was expected to supply a corps of 60,000 men. There was also the option of commandeering civilian bakers from occupied territory.

Gorgas’ bakery was tasked with delivering at least 8000 loaves every day and Gorgas had brutal and humiliating means at his disposal to ensure this target was reached. Smail, his superior officer, known to the Turks as the efendi (lieutenant), showed Gorgas how to use his whip to “discipline” his bakers. There is no evidence that Gorgas ever actually used it, but he did make a note for himself “that this method is, after all, probably the best one.” The violence meted out by the efendi more than compensated. However, the fact that the bakers usually produced no more than 6000 loaves per day was not attributed by Gorgas to the inhuman conditions they were working under. Instead, his description of “careless, lazy workers of limited intelligence” betrays his racist prejudices against his Turkish comrades.

With the advance of the soldiers at the front, the field bakery, too, moved further and further into occupied territory. Most of the bread produced was destined exclusively for the front, so the catering corps had to look for its own provisions elsewhere. They plundered livestock from farms and produce from local gardens whose owners had fled. During the advance on Bucharest, Gorgas counted a 500-strong flock of plundered sheep following the column. The troops took up quarters in abandoned houses and looting was the order of the day. Gorgas sometimes took part, but at other times he deplored it.

Shortly before Budapest a row erupted with efendi Smail. Gorgas hosted a lunch where he deliberately served pork to his Muslim guests without their knowledge. Gorgas recorded their reaction in his notebook: “Both of them looked at their plates, sniffed the air, then one of them said ‘dammusett’ [sic.], i.e., pork. And with that, as if of one mind, both stood up and left the room without a word.” A brief fisticuffs ensued the following day. Later that evening, Hassan the interpreter came to Gorgas. He reported that Smail, enraged by the fight, had gone to the stables and begun furiously whipping the horses. In his frenzy, he also beat one of the grooms to death.

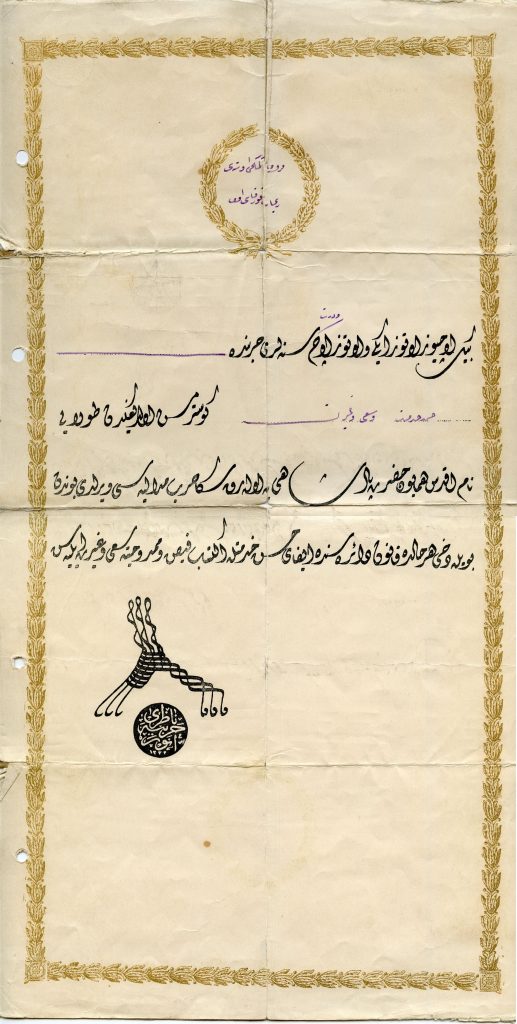

Despite this escalation, Gorgas did not report what had happened, ostensibly to protect his interpreter. Nevertheless, his superior was relieved of his post and replaced by a new lieutenant. At New Year 1916/1917 the Romanian army retreated to Moldova and the hostilities descended into a war of attrition. Gorgas’ posting also came to an end at this point. This is how he described his last evening with his Turkish comrades: “In the middle of the room […] in the glowing coals was a pot of water. […] mocca was brewed in each man’s cup with a generous helping of ground coffee. Cigarettes were handed round and then I had to tell tales of Berlin. […] some of them could only understand a word or two.” Prior to this, Gorgas had been presented with the Iron Crescent. He confessed that he still could not understand the speech made in Turkish at the ceremony by his new lieutenant. On his return to Germany, Gorgas was invalided out of the army because of the long-term effects of a gallbladder rupture, which also meant he had to close his own bakery in Berlin. Later, during the Weimar years, he was forced to continually look for work, moving from odd job to odd job.

[1] For more information, see Manfred Wichmann, “Kriegseintritt Rumäniens 1916”, URL: https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/erster-weltkrieg/kriegsverlauf/kriegseintritt-rumaeniens-1916.html, accessed: 15.08.2022.

Nico GeisenNico Geisen works in the Collection at the German Historical Museum. |