Criminal Case 527 – 10/92. The trial of Erich Honecker and his last speech

Thomas Jander | 2. Dezember 2022

Thirty years ago, criminal proceedings were instituted in the Berlin District Court against the East German politician Erich Honecker and other high-ranking members of the former GDR government and the SED (Socialist Unity Party) concerning the deaths of people attempting to flee across the inner-German border. It was supposed to be the trial of the century, but has largely been forgotten today. What is remembered above all is Honecker’s final published speech in court on 3 December 1992. Thomas Jander, head of the DHM’s collection “Contemporary Documents”, which contains the putative first version of the speech, discusses the trial and the speech in this DHM blog.

The end of the Honecker era

For thirteen years, Erich Honecker was the most powerful man in the GDR, in fact he was that for eighteen years in the SED. His era came to an end no less quickly than surprisingly. At the centre of power in July 1989, Honecker was still fairly invulnerable, when suddenly at a meeting of the government heads of the Warsaw Pact states, he had to cut short his stay due to a biliary colic and was brought to an East German hospital, where he underwent several operations and remained for almost two months. During this time, dramatic social and political events were taking place at home and in the neighbouring countries. Hungary had opened its borders to Austria, GDR citizens were fleeing day after day to the West, the West German embassy in Prague was overflowing with refugees, and thousands of people were demonstrating against SED rule in the larger East German cities. Nothing was heard from Honecker. When he returned to his offices, he turned a rigid and cynical eye on the developments. Not a single tear, he declared in the “Aktuelle Kamera” news broadcast, should be shed for those who fled the country. The leadership of the party and state then ostentatiously began preparing the celebrations for the 40th anniversary of the German Democratic Republic. Meanwhile, Honecker’s hitherto closest allies were cutting loose their ties with him and beginning to plan for the “Wende”, the turning point that would include Honecker’s removal from office. At a meeting of the SED Politburo on 17 October 1989, Willi Stoph made the proposal to release Honecker from his duties and select Egon Kranz as his successor. The Central Committee followed suit the next day, and the Volkskammer, the DDR parliament, confirmed Krenz on 17 October as the new head of state. Thus, Honecker was history. For the ex-head of state himself, the next three years meant a constant move from place to place, an odyssey that cannot be covered in this article.

The criminal case before the Berlin District Court

Preliminary proceedings against Honecker for abuse of authority and embezzlement were already initiated in East Berlin in 1989, which were expanded in January 1990 to include treason and other crimes against the state. When in the summer of 1990 protocols of the National Defence Council from the year 1974 under its chairman Erich Honecker were found, which contained the order to use firearms at the inner-German border, an investigative procedure charging multiple murder and multiple serious injury was opened on 8 August 1990. However, the collapse of the GDR state around this time also meant the closing of the GDR attorney general’s office, so that in the late afternoon of 2 October 1990, the 400 document files of the Honecker case were transferred to the attorney general’s office of the Federal Republic. Two weeks later, the Berlin-Tiergarten District Court, which was responsible for the case by reason of the Unification Treaty, issued an arrest warrant against Honecker: he was accused of manslaughter in four cases between 1983 and 1989. Twice the lawyers filed an arrest warrant, and twice the district court turned it down, for the last time on 6 March 1991. In the following week, Honecker and his wife Margot fled to the Soviet Union. When a year later it looked like Honecker would be extradited, Jutta Limbach, the Berlin Senator of Justice, announced that the attorney’s office had brought charges against Honecker before the Kammergericht, the highest Berlin Court of Appeal. Honecker was, in fact, brought to Germany on 29 July 1992, immediately arrested and remanded in custody in Moabit prison.

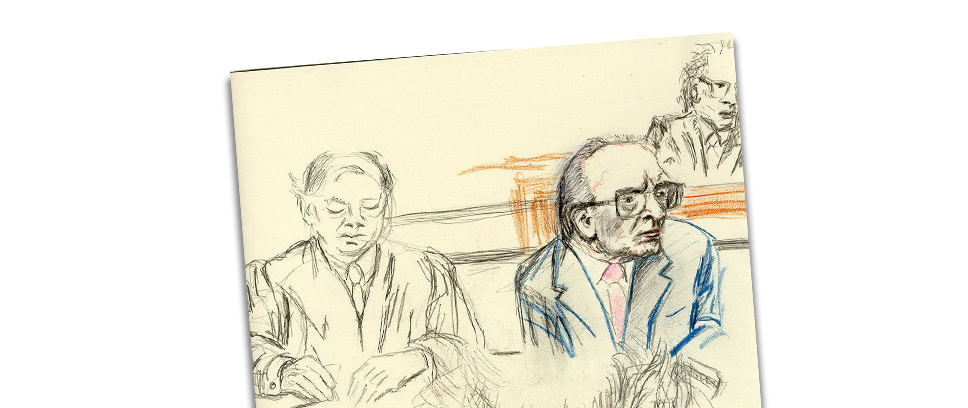

The trial before the 27th criminal chamber of the Berlin District Court began on 12 November, chaired in Room 400 by Judge Hans Georg Bräutigam. The chamber was the largest available in the aged courthouse from imperial times, but it was not large enough for all the participants. Room had to be found for the Bench with three professional judges and two lay magistrates, behind them two substitute judges and four substitute assessors, followed on the left by the six defendants – in addition to Erich Honecker, Erich Mielke, Willi Stoph, Heinz Kessler, Fritz Streletz and Hans Albrecht – alongside three defence lawyers for each defendant. Facing them sat the prosecuting attorney Christoph Schäfgen with three attendants as well as four joint plaintiffs and their representatives. In addition, there were around 150 journalists and spectators, including many supporters of Honecker.

The court convened twice a week for a maximum of three hours. The trial was planned for a total of 60 days of hearings. After the first day of the trial, lasting only 45 minutes, the number of defendants was reduced and the Stoph and Mielke cases were separated. On the second day, Honecker’s lawyers were first heard, then motions for fear of bias were submitted against the judge, and further motions were made concerning Honecker’s illness, cancer of the liver, which was heavily covered in the press, all of which delayed the proceedings. On the fifth day of the trial, 30 November 1992, the 783-page bill of indictment was read in a trimmed-down version. Due to Honecker’s malignant tumour and the dilatory tactics of his lawyers, the attorney general urged everyone to make haste, which is why the 68 cases of death at the border originally mentioned in the indictment were reduced to twelve cases. Honecker, too, was scheduled to make his statement on this 30th of November, but he wanted to put it off, and so the once most powerful man in the GDR held his final speech on the sixth day of the proceedings, 3 December 1992.

Honecker’s last speech

Erich Honecker might have been a great many things, but a great speaker he was not. He mumbled monotonously through his often long-winded public addresses in wooden, party-functionary German. But according to his lawyer Wolff, he had worked on this speech since he was first taken into custody. Honecker gave Wolff an initial typescript on 19 October, followed by a second, revised version on 26 November. The speech, sent to the press in 40 copies, comprised 14 pages; Honecker needed 70 minutes to deliver it, interrupted by a break. Striking for many observers was that Honecker, contrary to expectations, spoke in a forceful and loud voice, barely lapsing into his typical singsong. Jacqueline Hénard, who followed the trial in the courtroom for the FAZ, later wrote that the speech was held in the air of the “head of state of the GDR internationally recognised by more than one-hundred states.”

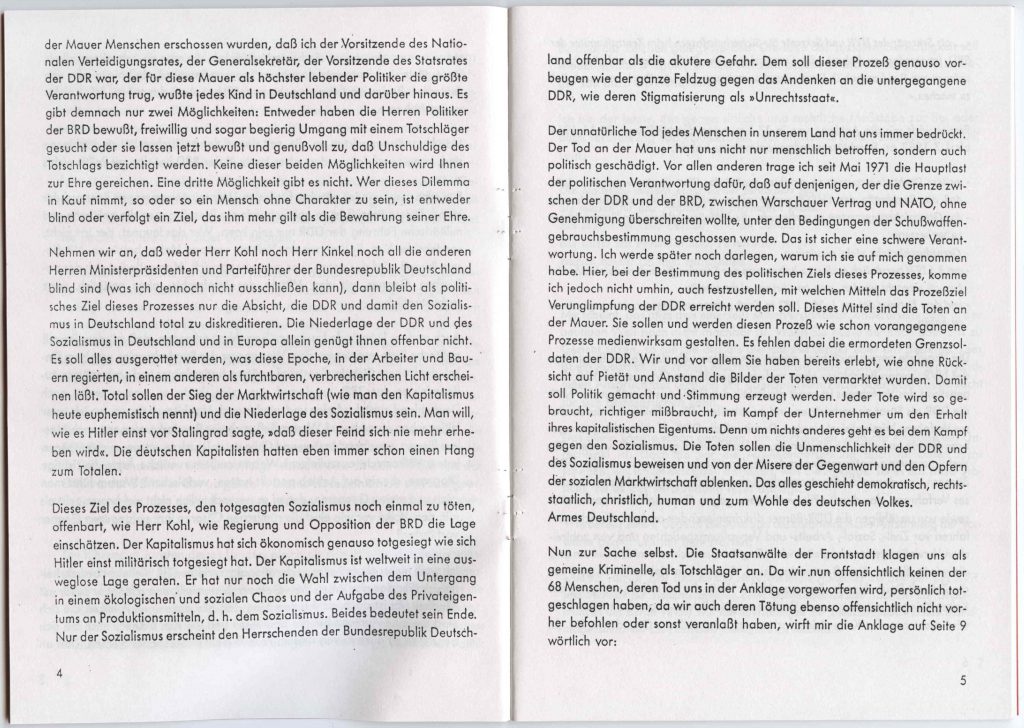

What Honecker had to say was hardly surprising. He disputed the legitimacy of the trial, would therefore not defend himself, and would no longer live to experience the verdict. The procedure was political and actually directed against the GDR, he argued. In essence, he pinned the responsibility for the border deaths he was accused of on the historical circumstances that required the closing of the border in 1961 and the building of the Berlin Wall, and on the two opposing military blocs, NATO and the Warsaw Pact. His influence was limited, he claimed, and the GDR was neither a leading power in the Warsaw Pact nor a world power that could have prevented this.

Ill.3 and 4: Brochure with the text of Honecker’s speech in the Berlin District Court. No pity, no regrets: “The unnatural death of any person has always aggrieved us.” [Deutsches Historisches Museum; Do2 95/1094]

Ill.3 and 4: Brochure with the text of Honecker’s speech in the Berlin District Court. No pity, no regrets: “The unnatural death of any person has always aggrieved us.” [Deutsches Historisches Museum; Do2 95/1094]

Since such “political decisions [very often, T.J.] cost lives,” Honecker brought up the Vietnam War, the Falkland Islands conflict, and the occupation of Grenada as examples where the political decisionmakers were not held accountable. Moreover, if the closing of the border had been prevented, it would have resulted “in the death of thousands or millions.” What he did not offer were words of pity, regret, or even personal remorse in the face of many hundreds of deaths that the border had cost in the course of it 28 years of existence. In the end, turning defiantly to the judges, he declared: “I am at the end of my declaration, do what you can’t help doing.”

The DHM’s collection “Contemporary Documents” preserves what is very likely the first version of this speech. It is an undated, handwritten, 38-page manuscript. Honecker wrote the first 22 text pages with a ballpoint pen, the remaining 15 with a fountain pen. The last pages in particular show signs of haste or excitement, since Honecker’s normally barely legible handwriting becomes almost indecipherable.

Parts of the contents of the original and final versions are identical, but there are also considerable differences. What remains is his claim that the proceedings were actually aimed against the socialist system of the GDR although the country is internationally recognised and that he himself received visits from the highest ranking representatives of the Federal Republic and was invited to visit them. Much space is devoted to the arrangement and defence of the border regime as a product of the Cold War and as a barrier against a nuclear war. Here, too, there is hardly a word about the victims: in the first draft there is only one such sentence, whereby those who were killed while fleeing are equated with deaths of the border guards.

It is above all the last quarter of the draft that does not reappear in the final version. Here Honecker gives free rein to his rancour against his erstwhile comrade and friend Mikhail Gorbachev. He had betrayed socialism, claims Honecker, had sold off the GDR for “less than 30 pieces of silver” and had given the Marxist dogma of class struggle the blame for the “misery of the 20th century”. In Honecker’s eyes, Gorbachev “could not have sunken deeper.” In the speech he later held, by contrast, Honecker mentions the former Soviet president only at the end and sardonically remarks that Gorbachev had been made an honorary citizen of Berlin, while he himself was dragged before the court, whereby both of them, except for small differences, had represented the same politics.

Ill. 5: The first page of the putative first draft of Honecker’s declaration before the court: “I stand here as a German communist […].” [Deutsches Historisches Museum; Do2 2017/1091]

Ill. 6: The last page of the putative first draft of Honecker’s declaration before the court: “I stand here as a German communist […].” [Deutsches Historisches Museum; Do2 2017/1091]

When one compares the two versions, doubts remain that Honecker composed the final version all by himself. He had had, of course, access to the indictment for months and had enough time to write and revise the speech so that a declaration could be formed out of an initially poorly structured and rather impulsive text full of gaps and digressions, a speech that Heribert Prantl described in the Süddeutsche Zeitung as “fastidious and accurate”. However, when one considers that Honecker was a seriously ill 80-year-old man, weakened by numerous operations and by his physically and mentally debilitating years of flight, such doubts are in order. The speech was moreover not the only text he wrote while in provisional detention: at the same time, he composed the “Moabit Notes”, a kind of political testament, an 80-page memo that was published in 1994. In a new edition from 2010, Margot Honecker revealed that Erich had written his texts by hand in Moabit in 1992 and sent them by post to Chile, where she typed them and sent them back to be edited, because “his handwriting […] was no longer very legible.”

So it can be surmised that the speech was a composite work of the Honeckers, for which Erich delivered the basic handwritten structure and Margot took over the rest. Margot Honecker clearly had a greater command of the language, formulating and supplementing the notes with examples, data and details. She advocated the same ideology, and it can be assumed that the time-consuming transfer of the manuscript pages did not take place very often. Already on 4 December 1994, the Tagesspiegel conjectured that “with the perhaps best speech that Erich Honecker ever held in his political life […] one hardly wants to believe that Erich composed it all by himself, as his defence lawyer Wolff asserts.”

After his declaration, Honecker did not speak another word in court, which was perhaps due to the fact that the trial came to a sudden end. First, there were medical testimonies that stated that Honecker had perhaps only three to six months to live, whereupon the defence called for a suspension of detention. The court dismissed this and the lawyers then entered an appeal before the Berlin Constitutional Court, stating that it was against the defendant’s human dignity to be subject to a trial, the verdict of which he would not survive to experience. On 7 January 1993, the trial was again “slimmed down” and the proceedings against Honecker were separated from the others. But only five days later, the District Constitutional Court decided in the interest of Honecker. On 13 January 1993, Erich Honecker was a free man and on his way to Chile.

History on trial

The legal historian Uwe Wesel was certain shortly before the end of the proceedings that it was a historical trial, but was not certain how it should be assessed in the future.

One must search far back in German history to find a head of state who was put on trial: in 1268, there was Conrad of Hohenstaufen, who was brought to justice and beheaded. In other words, a poor comparison. The Nuremberg Trials, where at least the second in command of the “Third Reich”, Hermann Göring, stood in the dock, were also not a good example for the assessment of the Honecker trial. At that time it was only about crimes that were committed or ordered after the beginning of the war by Germans: all other no less punishable crimes were not taken into account.

But the prosecutors at Nurnberg were aware of one thing: Nulla poena sine lege. Therefore, in Nuremberg, the legal basis for the indictment was created before starting the trial, albeit not without criticism; on the one hand, the prosecutors were firm and united, and on the other, the crimes were so outrageous and numerous.

In the case against Honecker et al., the prosecution wanted to stay on the safe side and thus to charge the accused according to GDR law. It never came to an intensive debate about that decision, because the trial did not last long enough. It would, however, been interesting to see how the contradictions, here only briefly touched upon, could have been resolved juridically. The members of the National Defence Council were charged as perpetrators, not as instigators. That was possible according to West German law, where the person, according to § 25 StGB, does not have to commit the crime himself in order to be a perpetrator, but not the case according to East German law, which recognised only direct perpetration (§ 32 StGB DDR). Furthermore, the criminal charge was manslaughter according to § 112 StGB DDR. However, this meant that illegally crossing the border was ruled in § 213 as a crime, and at the very latest with the law passed by the GDR Volkskammer in 1982 on the right to use firearms against border crossing crimes, there was no longer the legal basis for perpetration with manslaughter. It was thus sheer impossible to convict the border regime of the GDR and those responsible for it and for the deaths occurring through it as an illegal act or to indict persons for acting illegally according to GDR law.

On the basis of the construct developed by Gustav Radbruch according to which positive law becomes wrong when it stands in contradiction to justice and righteousness to an intolerable degree, it was therefore argued that the GDR had acted here inhumanely and cruelly to an intolerable degree by confining its population and shooting at those who were fleeing. It was also pointed out that the GDR had signed the Helsinki Accords in 1975 and thus recognised the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which sets forth the right to freedom of movement for all people. However, this right had never previously been legally asserted and was not enforceable, or rather it was not suited as a trial instrument to prove individual liability.

The principal trouble with the proceedings that were professed to be the trial of the century was that the attempt was undertaken to morally condemn an entire political regime and its representatives with the means suited merely for a criminal trial. That was wanting too much, too much at once, too jumbled, and in the end an excessive demand on the judicial machinery.

Thus, after Honecker’s speech, the historian Götz Aly summarised in the taz: “Without a doubt, the criminal procedure against Erich Honecker is not a mere criminal trial, but inevitably a political trial.” Only through the decision of the District Constitutional Court could the “constitutional state […] get its act together,” surmised Uwe Wesel after the trial was shelved, a trial that was not only unsuitable for the matter itself, but also full of embarrassing moments. One example should be mentioned for the sake of thoroughness: Shortly before Christmas, Judge Bräutigam, acting on the part of an assessor, requested an autograph of Honecker through his lawyers. On that day the lawyers had failed to get through one of their motions and so they informed one of the joint plaintiffs about the “autograph deal”, whereupon the plaintiff demanded that the judge be replaced because of bias. This was granted and Bräutigam was dismissed on 5 January 1993.

In his commentary on Honecker’s speech, Götz Aly further states that “not the judiciary, but rather the critical contemporary historical research in the next decades” will have to pass judgement on the speech and the significance of the trial. Today, however, one searches largely in vain for a broader historiographical discussion of this event. The unsuccessful trial itself with its satisfactory ending only for Honecker might possibly explain the apparent lack of interest of the historians. In the end, one must agree with Michael Stolleis, who states that jurisprudence is not a suitable means to fulfil the deeply human desire to see historical crimes and (criminal) perpetrators punished: the courts always come too late, are often too weak and flawed, and construe only formal conclusions. In the end, historical justice and even historical truth can only be achieved with difficulty, or, in fact, not at all.

|

Foto: DHM/Thomas Bruns |

Thomas JanderThomas Jander is Head of the Documents Collection at the German Historical Museum |