In Search of Women Industrial Photographers

Stefanie Grebe | 7 March 2023

Women are seldom represented among the industrial photographers whose works are preserved and shown in museums, archives and publications. On the occasion of the DHM’s current exhibition “Progress as a Promise. Industrial Photography in Divided Germany” Stefanie Grebe from the Ruhr Museum Essen sets out on an initial search for such women.

Due to the repeated requests over the years for photographs by Ruth Hallensleben (1898–1977), we staff members of the photo archive in the Ruhr Museum have asked ourselves whether there aren’t a number of other important women industrial photographers, particularly since the Ruhr Museum also owns part of the estate of the industrial photographer Evelyn Serwotke (1925–2009).[1] The exhibition presently on display in the DHM, “Progress as a Promise. Industrial Photography in Divided Germany”, therefore serves as a point of departure for an initial cursory research into the topic. In this undertaking, we are not interested in possible correlations between gender and aesthetic motifs or stylistic devices, but simply in the question of where the women industrial photographers can be found who (probably) existed or still exist and whether it is possible to ascertain how many of them were active at a particular point in time.

In our research, we begin with works commissioned by state-owned enterprises or by the industry that were photographed by women. The aim of such photos was to realise the visual expectations of the respective commissioner. The motifs of industrial photography range from the representation or staging of the enormity of the industrial installations, the products themselves, the manufacturing processes, and the companies’ own social services and facilities in post-war divided Germany.

Regarding a general research of industrial photography, it soon becomes evident that the proportion of female photographers is lower or at least as low as in the areas of artistic photography, architectural photography, journalism, war reportage, and fashion photography. The traditional kinds of training to become a photographer normally entailed either a photographic apprenticeship in a studio, training with a master photographer, attending a technical college, university studies, or – not uncommon in the area of photography – autodidactic practice and the attending amateur courses. In the best case, a woman wanting to become a photographer would have an apprenticeship covering the broad, comprehensive spectrum of industrial photography. Training in handling all types of cameras, techniques and genres of photography is a prerequisite for the successful mastery of the demands of industrial photography.

In our search for women photographers, there was the additional difficulty that when they were employed by a company they were not, as a rule, listed by name. The usage rights for photos are usually held by the company or industrial enterprise, whose viewpoint is to be realised in the commissioned photographs. No provision is made in the contract for an identifiable authorship of the photos. Ideally, research in the company’s archive could provide information about the photographer behind the otherwise anonymous photos, but this is often not recorded. If independent photographers were commissioned for industrial photographs, it can be assumed that they would insist on being named. In this case, company documents or external publications might provide the required information.

Individual art dealers and auction houses sometimes offer industrial photographs to the small group of photography collectors who do not explicitly specialise in prints defined as free art. Many industrial and architectural pictures, particularly from the early period of photography, are commercially available, and some commercial industrial photography from the 20th century can also be found on the art market. Alongside works by Albert Renger-Patzsch or Ludwig Windstosser, those of Ruth Hallensleben are sometimes available there. Otherwise, only individual works of industrial photography by women tend to turn up in those markets. Here it would make sense to search additional focal points such as object photography or reportages on the general area of industry, and not only those of scintillating monumental aesthetics.[2]

The situation of photography commissioned by the industry is not unlike that in the art market: only individual photographs or series can definitely be identified as those by female photographers.

For a resourceful search of women photographers, it can therefore be recommended to examine the archives of large companies, the publications of companies and enterprises, and other public archives where such photographs might be found. Another possibility is to follow in the footsteps of Reinhard Matz[3] to the archives he used for his studies. But there, too, there is no guarantee, because old personnel records are often destroyed. Perseverance and investigative skill are required.

One should have no illusions about the results in searching for female names in the overseeable number of publications on industrial photography. Here it is advisable to expand the geographic and temporal framework of the search if you do not want to be disappointed. The expanded search can lead, for example, to works by Marianne Strobl, Anne Winterer (Lichtbildwerkstatt Hehmke-Winterer), Erna Hehmke-Wagner, Charlotte und Gerda Meyer, Ursula Litzmann, Liselotte Purper, Lotte Laska, Abisag Tüllmann, Ulrike Mosbach and Evelyn Richter.

Industrial photography today presents a very different picture. Since the industrial sector has largely shifted to low-wage countries and there is no great visual interest in images of automated industrial production, of which there is still much in Germany, we now find an increase in photographs oriented on “editorial design” or business photos in industrial situations. These are often adorned with international photo models in desaturated or excessively colourful surroundings, symbolising progress and the future. There are some women photographers who practise this new kind of commercial photography, also in the area of industrial photography. However, the new industrial photography seldom resorts to pictures of gigantic halls or the glorification of machines. They symbolise the old world before digitalisation.

Just as a comprehensive survey of industrial photography is lacking in Germany, it would be highly desirous to continue to expand research on female industrial photographers. The question posed at the beginning of this article: Where are all the women industrial photographers? can be answered with the call for specific research in industrial, company and national archives. The second question about the number of them active in a particular epoch can unfortunately not be answered. Empirically reliable statistics that could verify this are not available at this time. The two collections of works by the industrial photographers Ruth Hallensleben and Evelyn Serwotke in the photography archive of the Ruhr Museum remain – until other collections turn up – exceptions to the rule. In a positive sense, they are exceptional representatives of women’s industrial photography, but negatively expressed they represent the disproportionately low number of women working in this field. I hope that this brief research will whet the appetite for a continued search for such works. Although the evidence is yet to be found, we can assume that they do exist.

[1] Part of Evelyn Serwotke’s industrial photographic works are in the LVR Industriemuseum Oberhausen and other parts in the photography archive of the Ruhr Museum Essen.

[2] This kind of expanded search turns up such examples as Hildegard Dreyer, Edelgard Rehboldt and Monika von Boch as photographers who were also sometimes commissioned to take industrial photographs.

[3] In the 1980s, Reinhard Matz examined many company archives for the first time in search of industrial photography. His book Industriefotografie. Aus Firmenarchiven des Ruhrgebiets, Essen 1987, has also been published under the same title as a microfiche.

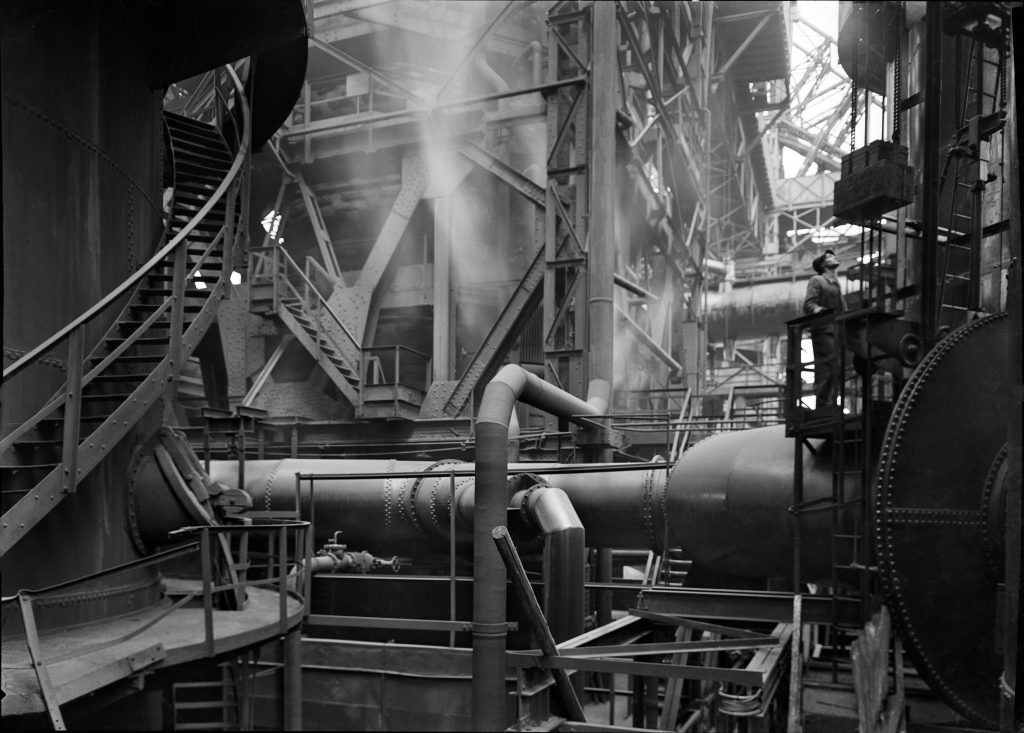

Header: Ruth Hallensleben / Fotoarchiv Ruhr Museum: Steelworks of the Bochum Association, Bochum 1950 © Essen, Ruhr Museum

I would like to thank Gabriele Conrath-Scholl, Thomas Dupke, Claudia Fährenkemper, Manuela Fellner-Feldhaus, Tillmann Franzen, Anna Gripp, Marion Scharmann and Kyllikki Zacharias for information and stimulating conversations during my search for female industrial photographers.

Stefanie GrebePhoto historian, photographer, lecturer, curator and since 2015 head of the Photographic Collection and Photo Archive at the Ruhr Museum, Essen, on the Zollverein World Heritage Site. Main research interests: Staging authenticity in documentary photographs and the contextuality of photographs. Curator of various exhibitions at the Ruhr Museum; most recently “Beyond Emscher. Fotografische Positionen aus der Gegenwart” and “Die Emscher. Bildgeschichte eines Flusses” (2022/23); and “Wir sind von hier. Türkisch-deutsches Leben 1990. Fotografien von Ergun Çağatay” (2021). |