Take to the Streets on 8 March!

Germany’s first Women’s Day took place in 1911, with 8 March becoming the established date from 1921. In 1977, the United Nations also declared 8 March to be International Women’s Day. In this essay, Veza Clute-Simon of the Digital German Women’s Archive outlines the demands of women’s associations and women’s groups in their campaign to abolish paragraph 219 of the German penal code. The author provides some context by looking back at the history of the country’s abortion laws.

Events marking the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in Germany will be taking place over the next few months. The message of this anniversary is “women make history”, which is also the motto of the feminist archives, libraries, and documentation centres organized under the aegis of the i.d.a.-Dachverband. Established during the years of the Women’s Liberation Movement, these institutions complement history not only in terms of scholarship about women, but also through the creation of a new historiography with an emancipatory agenda:

“It is […] present-day dynamics of conflict that impel us to look to the past. We want to familiarize ourselves with […] their pre-history in order to find possible ways of successfully overcoming them,”

explains the philosopher Herta Nagl-Docekal in an overview of the approach.[1] One of these “dynamics of conflict” came up for discussion in the Bundestag, the German national parliament, on 22 February 2018.

#wegmit219a – “Abolish Paragraph 219a”

Women’s autonomy over their bodies is currently the subject of parliamentary debate. The debate relates to a recent change to the law on pregnancy terminations, which are widely believed to be legal in Germany. However, terminations are in fact listed in the penal code, albeit with certain circumstances in which prosecutions are not pursued. The phrase “illegal but exempt from prosecution” has grave consequences for women seeking help and hoping to exercise their rights. Basic training for gynaecologists in Germany does not include the latest best practice for terminations. Hospitals make frequent appearances in the headlines for refusing to give women medical care on religious grounds. Medical assistance is frequently hard to find. Yet purely factual information about terminations is near non-existent on the Internet: in November 2017 a doctor was convicted for making this sort of information available online. However, the judgement sparked a protest movement that is now making itself heard in parliament. The hashtag #wegmit219a captures the movement’s overall goal: the abolition of paragraph 219a of the German penal code.

Historical Review

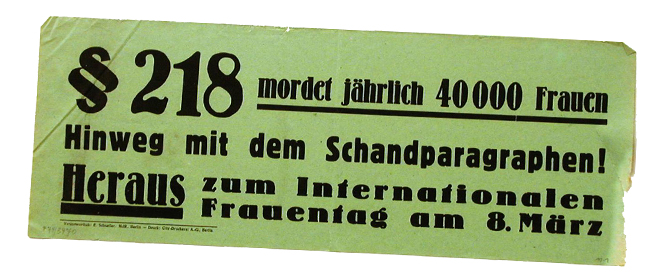

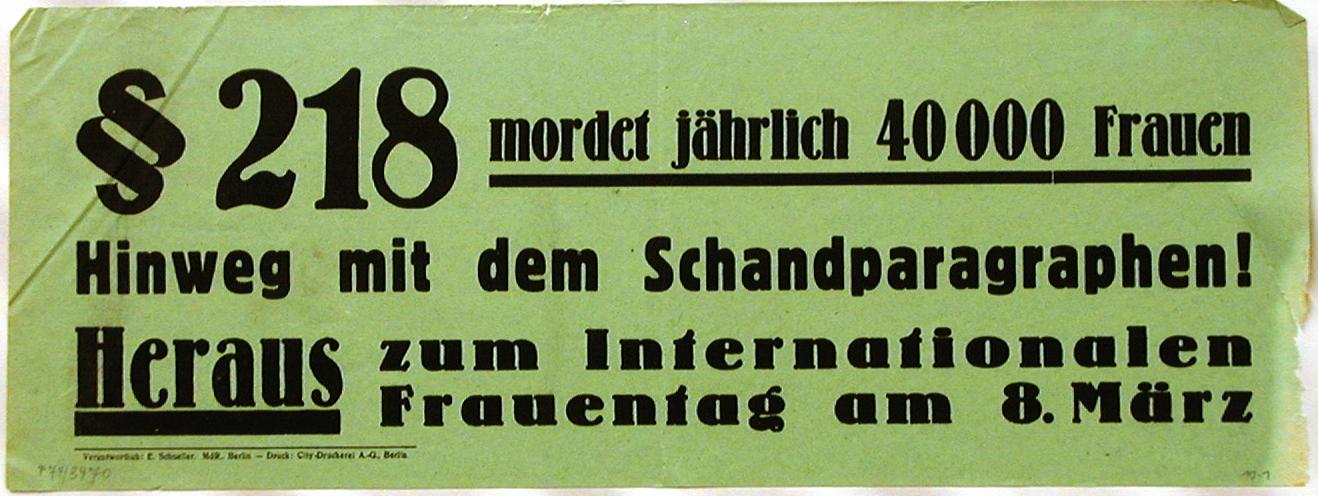

A look back through history illustrates that this struggle for physical autonomy is already a century old. A poster for Women’s Day in 1924 proclaims: “Paragraph 218 kills 40,000 women every year. Down with this disgraceful paragraph!”

Poster for Women’s Day, “Paragraph 218 kills 40,000 women every year. Down with this disgraceful paragraph!”, 1924/1933 © DHM

Featuring artwork by Käthe Kollwitz, this poster for the KPD (the Weimar-era German communist party) also dates from 1924: “Down with the abortion paragraphs!” The KPD also made repeated demands in parliament for the repeal of paragraphs 218 to 222 of the German penal code.

Poster for the KPD “Down with the abortion paragraphs!”, Käthe Kollwitz, 1924 © DHM

The physical suffering and existential threat that (yet another) pregnancy could mean for women in this period are clear to see in this poster. For women in the 1920s not only lacked access to professional pregnancy terminations, but also had no reliable forms of contraception. Having large numbers of children resulted in many families living in existential poverty. Women therefore underwent terminations despite it being illegal, which exposed them to the double risk of unsafe abortion procedures on the one hand, and possible prosecution on the other.

These two posters from 1924 were already voicing two of the central arguments that can still be heard in this year’s protests: banning abortions does not lead to a reduction in pregnancies being terminated, but instead increases the dangers involved. Banning information on abortions does not lead to a reduction in pregnancies being terminated, but merely worsens the plight of women.

The spirit of National Socialism

A reform introduced in 1926 reduced sentencing for women who had abortions (and those who helped them) to “just” two years in prison, and no longer manual labour in a house of correction. In 1933, however, the Nazis tightened the abortion ban and added paragraph 219a to the penal code.

Even today, the “advertisement” of terminations is still banned by paragraph 219a, despite the fact that the professional code of conduct for German doctors already forbids self-promotional advertisements of any kind. Their professional code does, however, quite clearly permit doctors to produce factual, medically-related information. The near unavailability of this sort of factual information applies only to terminations, and this will remain the case for as long as paragraph 219a is used to prosecute doctors whenever information of this kind is seen through the prism of the penal code – and so (mis)interpreted as “advertising”.

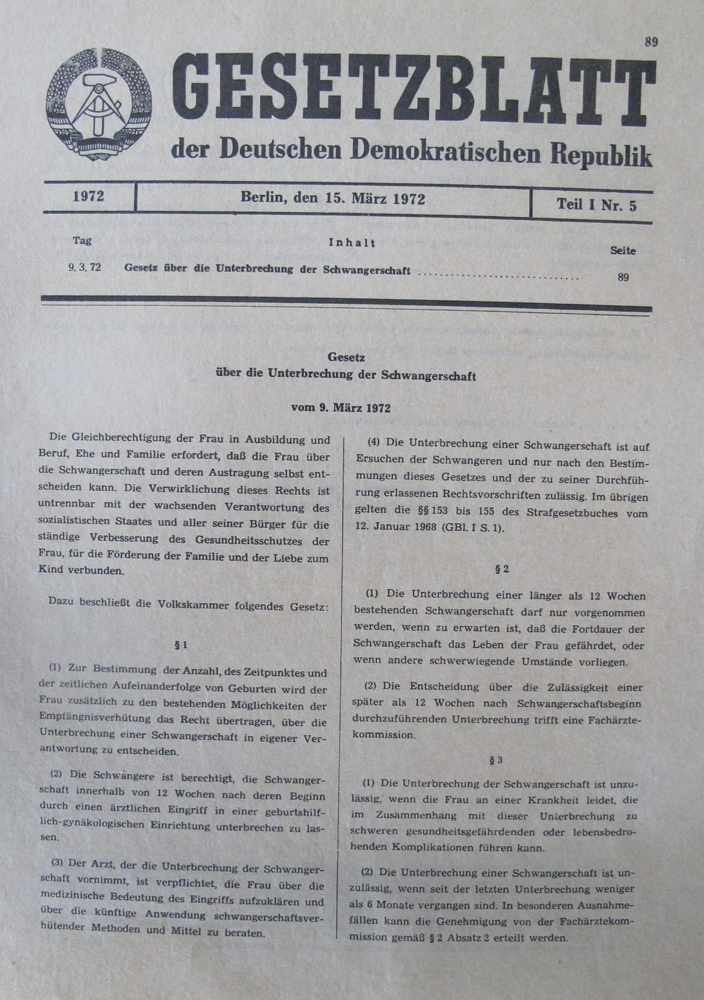

An item in the DHM’s permanent exhibition, a law journal from the GDR, bears testimony to how women in Germany once enjoyed greater autonomy over their bodies.

Law journal from March 15, 1972 about law on terminations, GDR © DHM

On 9 March 1972, the GDR’s “Volkskammer” (“People’s Chamber”, or parliament) passed a law on terminations. For the first time, women could decide for themselves in the first twelve weeks of pregnancy whether to have a termination. It is hardly surprising that East German women protested against the threat of this East German law being lost in the transition to West German law and took to the streets, for example, in April 1990. Still in force today, the resulting compromise ultimately worsened the situation for East German women. The paragraph from 1933 remains in force.

Source

[1] In: “Frauengeschichte, Geschlechtergeschichte, feministische Philosophie. Ein Gespräch zwischen Herta Nagl-Docekal, Edith Saurer, Ulrike Döcker und Gabriella Hauch”, in: Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften, 6 (1995), 2, p. 276.

Author: Stephan Röhl. This picture is published under Creative Commons Licence. |

Veza Clute-SimonVeza Clute-Simon studied socio-cultural studies and is involved in the queer feminist action group she*claim. She is currently writing for the blog of the Digital German Women’s Archive as part of her Humanity in Action fellowship. In her articles, she writes about items of interest found in the collections of the feminist archives. These include a box containing material on the West Berlin Lesbian Action Centre, which is held at the Lesbenarchiv Spinnboden, and the letters of Hilde Radusch, whose archive is located at the FFBIZ – feministisches Archiv e.V. |