Queer History

May is Queer History Month in Berlin. It marks an opportunity to reflect on the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, and intersex people from the past and present. Here, Florian Wieler and Katja Hauser from the Network “Queering Berlin Museums” explain what Queer History Month is all about – and ask just how queer German history really is.

For some years, the word “queer” has featured regularly in the media and politics. Historically, it meant “peculiar”. In the English-speaking world, it was used for a long time as a derogatory term to describe people who did not conform to the normative view that only a man and woman could feel desire for each other. From the late-20th century (if not earlier), the term underwent a process of appropriation and reinterpretation. Whether used as a term of positive self-identification or as a concept in academia and political activism, “queer” has come to signify everyone and everything that self-confidently deviates from the supposed norm – and in so doing, opens up this “norm” to scrutiny. Looking back at history plays an important role in this process. Making queer lives from the past visible reveals how society has always been more diverse than the “hegemonic” – that is, prevailing, heteronormative – perspective would have us believe. Like Black History Month in February, the aim of Queer History Month is to provide opportunities for telling (hi)stories that would otherwise garner little attention. The Deutsches Historisches Museum’s permanent exhibition also features exhibits and stories that reveal the queer side of Germany’s past.

How gay was Frederick the Great?

Antoine Pesne, Friedrich II., King of Prussia (1740-1786), around 1745 © DHM

The issue of Friedrich II’s sexuality is a recurrent theme in biographies of the Prussian king (who is usually referred to as “Frederick the Great”). Since sexual activity usually takes place in private, it is often only possible to speculate about Friedrich’s inclinations. Some biographers offer a wholehearted “defence” of Friedrich’s heterosexuality and underline his small number of relationships with women. From 1733, Friedrich was married to Elisabeth Christine von Braunschweig (Brunswick)-Bevern. Their relationship was cool and the couple remained childless. A number of clues suggest that, like his brother Heinrich – who was fairly open about his homosexual proclivities – Friedrich was attracted to the male sex. For example, correspondence between Friedrich and his brother attests to their rivalry over Johann Friedrich von Marwitz, a page at court who had caught the eye of both men. Furthermore, his authoritarian father Friedrich Wilhelm I had once called Friedrich a ‘sodomite’ and reacted to a failed escape attempt by the then-crown prince by ordering the execution of his beloved friend, Hans Hermann von Katte.

Observations of this nature often fail to bear in mind that sexual identity in this period did not take the form we imagine today. The social distinction between heterosexual and homosexual people emerged from the medical discourse of 19th-century Europe. At the time of Friedrich II, same-sex sexual acts were considered depraved and – defined by reference to the biblical concept of sodomy – even punishable by death. (Although it bears mentioning that poorer sections of society were considerably more likely to face prosecution than the wealthy.) Nevertheless, homosexuality was viewed as part of general human behaviour and not ascribed to any particular category of person.

The view that same-sex desire was an innate, immutable characteristic and hence ‘inevitable’ was taken up by such early pioneers of the gay liberation movement as Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and Karl Maria Kertbeny to support their campaign for the decriminalization of homosexuality. In 1869, Kertbeny (an Austro-Hungarian writer) made the first public reference to homosexuality – a word he had himself coined. The term subsequently achieved general currency, while others (such as “uranism”, coined by Ulrichs) fell by the wayside.

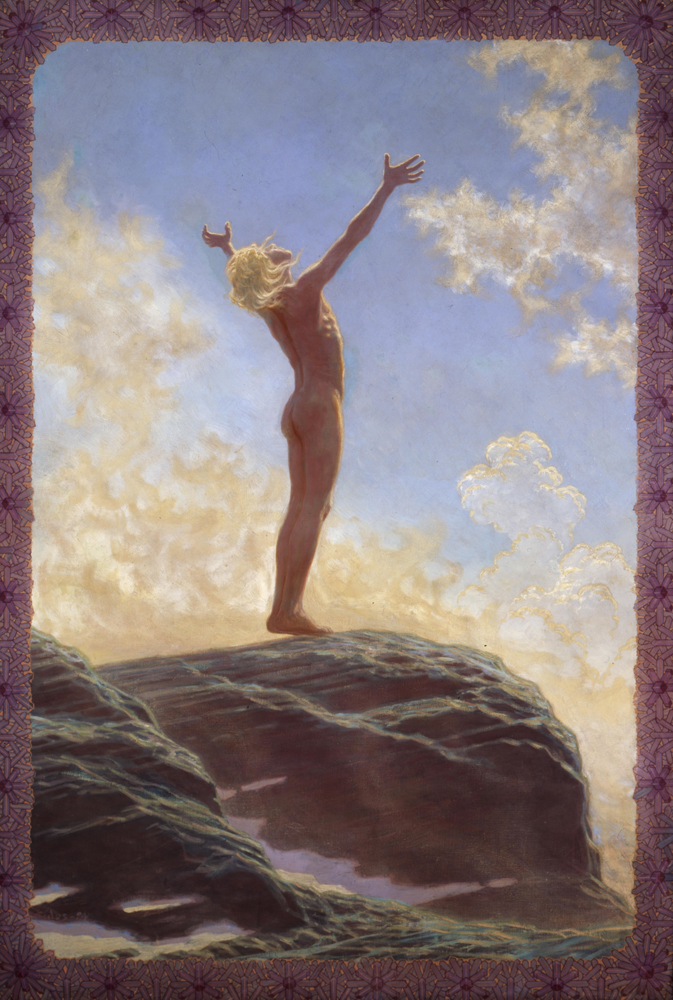

Hugo Reinhold Karl Johann Höppener, Prayer to the Sun, 1894 © DHM

The fight to repeal Paragraph 143 of the Prussian legal code, and later Paragraph 175 of the German Reich’s statute book, paved the way for the creation of the first gay civil rights movement. Founded in Berlin in 1897, the “Scientific-Humanitarian Committee” was the world’s first organization to campaign for the decriminalization of sexual acts between men. There followed numerous other associations, groups, and magazines dedicated both to political activism and entertainment. This was also the period in which women’s rights campaigners Johanna Elberskirchen and Anna Rüling became politically active as the first pioneers of a lesbian liberation movement.

“Entirely masculine” – “More feminine” – “Mixed”

Lotte Laserstein, The Motorcycle Driver, 1929 © DHM

A key figure in this development was the doctor and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. In the course of research on what he described as “sexual intermediate stages” of men and women, he defined innumerable “sexual types” on the basis of physical features, characteristics, and desires. Hirschfeld’s research was not premised on understanding these various manifestations in terms of pathological deviations from a norm, and hence he is seen from our own contemporary perspective as a pioneer of the concept of sexual and gender diversity. Hirschfeld also coined the term “mental transsexuality” for people who want to take on the physical characteristics of the “opposite” sex in line with their own gender identity, while his entourage at the Institute for Sexual Research (which he founded in 1919) campaigned for the legal protection and recognition of trans* people.

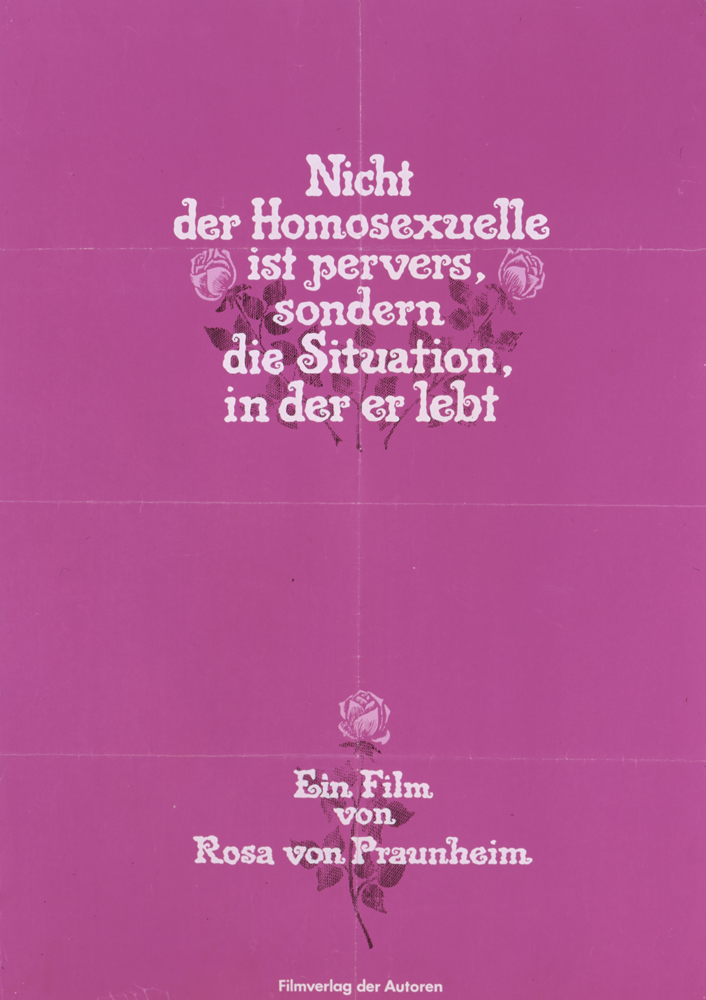

During the 1920s, the various homosexual organizations coalesced into a mass movement. One factor in this development was the lively gay and lesbian subculture centred around Berlin. Here gay men and women could visit a wide variety of bars, clubs, and cafés – such as the legendary “Eldorado”. After the National Socialists came to power in 1933, this movement was crushed. Gay and lesbian life was suppressed; homosexual men were persecuted, prosecuted, and murdered. It was not until the West German government eased Paragraph 175 in 1969 that a second wave of campaigners emerged out of the era’s maelstrom of social activism to form a diverse gay and lesbian movement. Campaigners in this period knew very little about their predecessors from the first wave of gay activism. Efforts to close gaps in this knowledge only came about in the following decades.

Poster for a film about homosexuals, 1971 © DHM

The Network “Queering Berlin Museums’”was founded in 2016 as part of the “Homosexuality_ies” exhibition organized by the Schwules Museum* Berlin and the Deutsches Historisches Museum. Its aim is to provide a forum for exchange and information. It also seeks to promote museum practice that adopts an equitable approach to sexual and gender diversity, with a view to counteracting mechanisms of social discrimination.