In Search of a Name

The Deutsches Historisches Museum is currently presenting an intervention in the Permanent Exhibition under the title “REVEALED BY THE REVERSE. The hidden history of a painting by Adolph Menzel”. The topic of this event, which is the first exhibition entirely designed by the Curatorial Trainees Susan Geissler, Darja Jesse and Tobias Schlage, is the reverse side of the painting “Borussia” by Adolph Menzel. The back of the painting contains various writings and labels, which, when carefully investigated, reveal information about the owners and provenance of the painting, as Tobias Schlage points out in this contribution.

As Curatorial Trainees we already began to develop the themes for our intervention in the summer of 2017, whereby we found the complex history of the “Borussia” by Adolph Menzel (1815–1905) to be especially interesting and moving. Before the artwork came to the Deutsches Historisches Museum, it had attracted a great deal of public interest. It was the first artwork in possession of the Federal German State to be restituted by a Berlin museum to the rightful heirs after conclusion of the “Principles of the Washington Conference” in 1998. During the time of the Nazi regime the owner had been forced to sell it under pressure.

But what methods and what criteria can be used to determine the provenance of an artwork – where it came from and who owned it? Where do we begin searching for the facts? Is such information hidden in the work itself? Are there clues about former owners or perhaps gaps in the information?

Reverse and obverse of the painting “Borussia”, Adolph Menzel, 1868, Oil on canvas, Berlin © Deutsches Historisches Museum

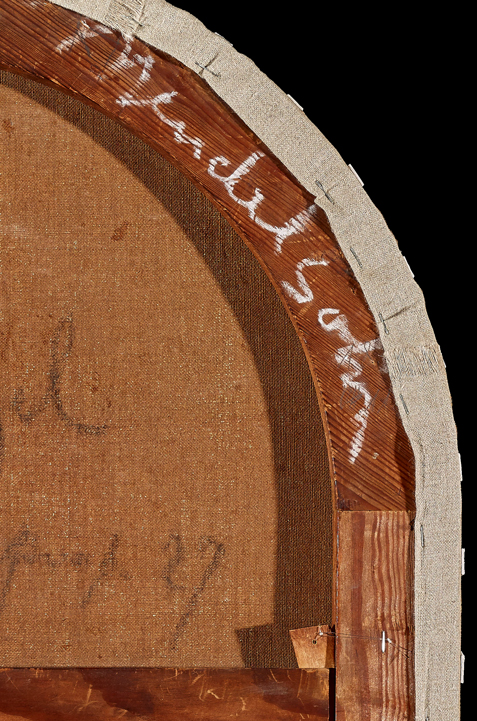

The backs of paintings are often the key to their provenance, but they are seldom seen in exhibitions. In our intervention, however, it is precisely the reverse of the “Borussia” with all its puzzling numbers, labels and names that is at the centre of our exhibition. In order to present the unknown history of the painting as completely as possible to the public, it was necessary to inspect all of these notations very carefully and to think about what they could possibly mean. The name “Mendelsohn” can be found three times on the back of the painting. Since I wondered who the Mendelssohns really were, I tried to find out more about the family.

Reverse of the painting “Borussia” with the lettering “Mendelsohn”, Adolph Menzel, 1868, Oil on canvas, Berlin © Deutsches Historisches Museum

Contemporary newspaper articles as a first point of reference

In the wake of a famine in East Prussia, the painting “Borussia” was created for a charity bazaar held at the Berlin Palace, which contemporary newspapers reported on. According to the reports the “Borussia” was bought by “Privy Councillor Mendelssohn”. Moreover, his wife, “Mrs. Privy Councillor Alex. Mendelssohn”, belonged to the organisational committee of the bazaar. Exhibition catalogues and other literature on Adolph Menzel provided me with further information about the Mendelssohn family.

Privy councillor Alexander Mendelssohn (1798–1871), purchaser of the painting “Borussia”, Robert Jefferson Bingham (1824/1825–1870), Paris, ca. 1860/1865, Albumen print, cardboard, Berlin © private collection

In 1848, Alexander Mendelssohn (1798–1871), scion of one of the most famous Jewish families in Berlin, had become senior director of the private bank “Mendelssohn & Co.”, founded by his forefathers at the end of the 18th century. His residence was located in the original bank house of the thriving company at Jägerstrasse 51, in central Berlin; it was here that he brought the painting “Borussia”. In addition to running the bank, Alexander was an active art collector, patron of the arts and philanthropist. As I was able to learn from exhibition catalogues and documents in the Central Archive of the State Museums of Berlin, the painting was later loaned to two exhibitions of the works of Adolph Menzel. Alexander’s son Franz von Mendelssohn (1829–1889) lent out the artwork in 1885 and his offspring Franz von Mendelssohn (1865–1935) again twenty years later. In the files I also found a note about the insurance value of the painting amounting to 15,000 marks –important evidence for the later forced sale.

Privy councillor Franz von Mendelssohn the Elder (1829–1889), owner and lender of the painting “Borussia” for an exhibition celebrating Menzel’s 70th birthday in the Berlin Royal Academy of the Arts, Royal court photographers H. Lehmann & Co., Berlin, ca. 1865/1870, Albumen print, cardboard, Berlin © private collection

Franz the Younger (1865–1935) and Marie (1867–1957) von Mendelssohn, owner and lender of the painting “Borussia” for a retrospective on the occasion of the death of Menzel, in the Royal National Gallery in Berlin in 1905, Fotoatelier Wilhelm Fechner, Berlin, ca. 1890/1895, Albumen print, cardboard, Berlin © private collection

The Mendelssohn Society founded by family members in 1967 is currently located in the former bank house. In the permanent exhibition there, various objects from the possessions of the Mendelssohns and Mendelssohn Bartholdys recall the unique history of the extended German-Jewish family of bankers, philosophers, artists and musicians. Despite instructive conversations and various documents and photographs with interesting insights into the family history that were kindly provided to me by the society’s archive, I was unable to find further information about the painting.

Family albums and mountains of documents

However, the Mendelssohn Society brought me in contact with the granddaughter of Marie von Mendelssohn (1867–1957), the last owner of the “Borussia”.

Marie von Mendelssohn, née Westphal (1867–1957), last owner and seller of the painting “Borussia”, no location, ca. 1925/1935, later print, baryta paper, Berlin © Private collection

The encounter with the granddaughter was not only extremely impressive, but she also became my most important source of information. First, we met in front of the painting in the Deutsches Historisches Museum’s Permanent Exhibition and discussed initial details. Later I was allowed to examine several family albums. I now had first-hand knowledge of what had been missing in the literature. She and other close relatives were able to tell me what happened to the painting after 1905, which they said had at that time been located in the cashier’s hall of the bank house.

Bank house and residence of the Mendelssohn family at Jägerstrasse 51, Berlin, Königlich Preußische Messbild-Anstalt, Berlin, ca. 1885/1890, baryta paper, Berlin © Architekturmuseum of the Berlin Technical University

The Nazi terror against Jews and thus against the Mendelssohn family steadily increased after 1935. According to the business records of the Haberstock Gallery from the Haberstock archive in Augsburg, Marie von Mendelssohn, represented by the bank, was forced to sell the artwork in April 1937 to the art gallery owner Karl Haberstock (1878–1956) for the then paltry sum of 19,000 Reichsmarks. In 1940 Haberstock then sold it to the Reich Chancellery for 48,000 Reichsmarks. It is entirely evident that the sum that Marie von Mendelssohn received for the painting was far too little. Although Marie’s granddaughter did not have a photograph of the painting, an inventory of the bank house or a photo of her grandparents’ villa, she was nevertheless able to lend me photographs of the most important protagonists for our exhibition.

A last piece of evidence finally led me to the Mendelssohn Archive of the Berlin State Library, the Central Record Office of Berlin and the Berlin-Charlottenburg magistrates’ court. The Mendelssohn Archive contains numerous family letters, several photos of the family and parts of the bank house archive. Despite numerous documents and illustrations, it did not have any evidence about “our” “Borussia”. The Central Record Office and the magistrates’ court contain all documents referring to the buildings in Jägerstrasse and Berlin-Grunewald. From the registry of deeds I was able to find out something about the acquisition of properties by the Mendelssohns in Berlin and the forced sales to the Nazi regime – yet there was no information about the “Borussia” itself.

In hindsight, the research on the name “Mendelsohn” on the back of the painting turned out to be real detective work. Although the exact whereabouts of the painting within the Mendelssohn family could not be substantiated by photographs, it was possible to clearly trace the path of the “Borussia” from purchase to forced sale by means of records, documents, catalogues and personal conversations with family members.

The return of the painting to the Mendelssohn family was first made possible after the reunification of Germany and in particular by the “Washington Principles” of 1998. The “Washington Principles” are part of an international agreement that attempts to find solutions for the restitution of Nazi-confiscated cultural assets. However, the principles are not based on legal norms. It was only in this way possible for the family to successfully assert their claim to restitution after expiration of the statute of limitations 30 years previously.

Provenance research has meanwhile become one of the central tasks of museum work. It pursues the aim of satisfying the ethical standards in dealing with museum collections and in particular the aim of fulfilling the principles set down during the “Washington Conference”. The reconstruction of the history of ownership of the painting “Borussia” within our exhibition demonstrates how important, protracted and extensive provenance research can be. The investigation of the name Mendelssohn was only part of the whole.

Further sources:

Bertz, Inka / Dorrmann, Michael (Hg.): Raub und Restitution. Kulturgut aus jüdischem Besitz von 1933 bis Heute, Ausstellungskatalog, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main 2008.

Keisch, Claude / Riemann-Reyher, Marie Ursula (Hg.): Das Labyrinth der Wirklichkeit. Menzel 1815–1905, Ausstellungskatalog, Köln 1996.

Mendelssohn Gesellschaft e.V., URL: http://www.mendelssohn-remise.de.

Schoeps, Julius: Das Erbe der Mendelssohns. Biographie einer Familie, Frankfurt am Main 2011.

Uebel, Lothar: Die Mendelssohns in der Jägerstrasse. Das Haus Mendelssohn Jägerstrasse 51 in Berlin, Berlin 2001.