Leipziger Strasse 4, Berlin

The German Reichstag in 1889 in the photographs of Julius Braatz

Carola Jüllig and Juliane Hähnlein | 13 January 2021

In January 2020 the Deutsches Historisches Museum received an offer to purchase a very special portfolio of photographs . It came from the holdings of the Bismarck family and contained a collection of photos of the old Reichstag – the building and people – that was already known under the name “The German Reichstag and its Home” and is now an important object in the photo collection of the DHM. In this DHM blog, Juliane Hähnlein, research volunteer at our museum until October 2020, and Carola Jüllig, head of the photo collection, focus their attention on the Bismarck family album and on a little-known aspect of German history.

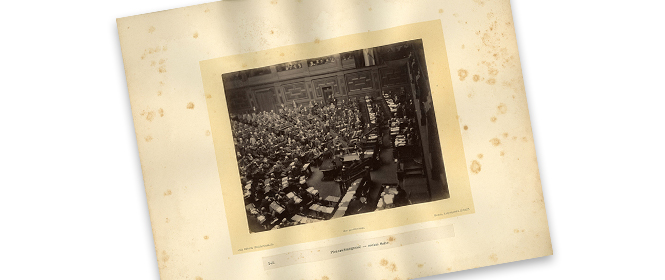

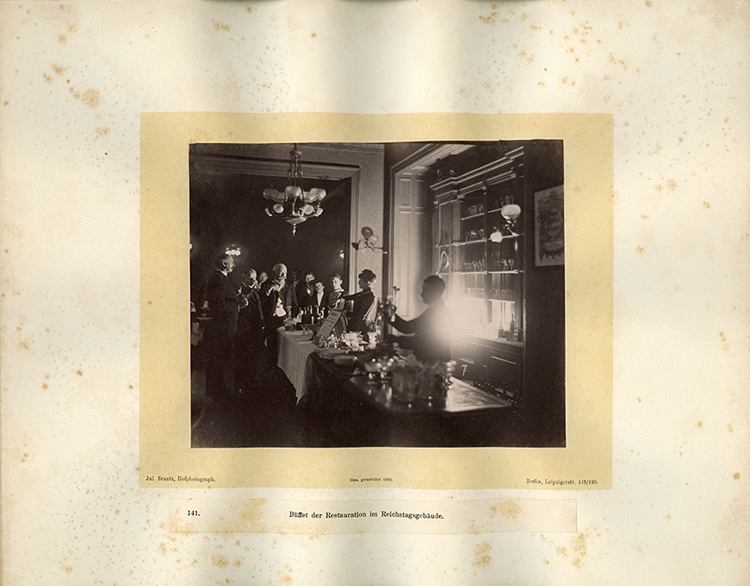

In a total of 184 photos the photographer Julius Braatz (1844–1914) captured images of the delegates, attendants and rooms of the old parliamentary building at Leipziger Strasse 4 in April and May of the year 1889. Some of them were taken on the day Chancellor Otto von Bismarck entered the building for the last time, on 18 May 1889.

That Julius Braatz was given the opportunity to take the photographs was a novelty and an exception for both the Reichstag and for photography itself. Never had a photographer advanced all the way into the offices of the delegates, let alone that of Bismarck; Braatz took the initiative himself to document the old Reichstag in “snapshots” before it moved into the new Reichstag building.

The old Reichstag building

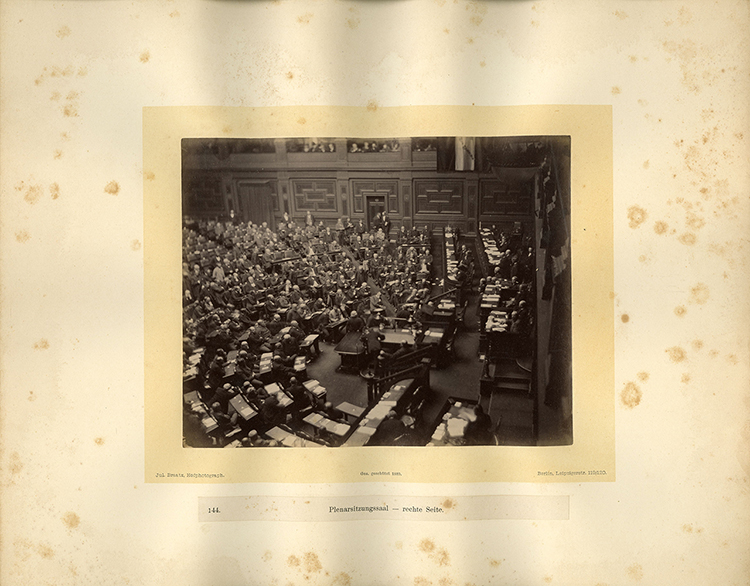

Parliament sat in the house at Leipziger Strasse 4 until 1894, when the Reichstag building at Königsplatz, designed by Paul Wallot, was completed, which from then on acted as the representative seat of the German Empire and home of the parliament. The old building in Leipziger Strasse had an assembly hall, lounges, offices, administrative rooms and a library as well as a large foyer, where most of Braatz’s group portraits were made. The Reichstag building at Leipziger Strasse 4 disappeared quickly from public remembrance because no photo of the exterior of the house exists. It was originally built for the Royal Prussian Porcelain Manufactory. Braatz’s photos show a number of functional rooms, such as writing and reading rooms, and even the “Restauration” where the delegates could get something to eat and drink.

The delegates

Since 1874 there had always been 397 delegates in the parliament. Because it was not permitted to pay parliamentary allowances until 1906, less wealthy candidates were at a disadvantage. Nonetheless, alongside numerous land and factory owners, there were a few artists, farmers and craftsmen sitting in parliament, among them the journalist Wilhelm Liebknecht and the master wood turner August Bebel. In the election of 1887 the social democrats received 10 percent of the votes; on the other side, Bismarck had the support of the electoral alliance of German-Conservatives, National-Liberals and the German Reich Party, giving him an absolute majority of more than 60 percent of the seats.

Long exposure times were needed in the sombre parliamentary rooms, which meant that the delegates had to remain still for a moment when being photographed. They did not always succeed in not moving, so that the facial features are occasionally blurred, which gives the photos a special charm. To compensate for some of the worst flaws, Braatz sometimes used montage to replace the blurred heads with shots from other photographs.

For the group photos the delegates were usually assembled according to parliamentary factions. Braatz photographed the delegates from the conservative or national-liberal spectrum more than any others – dignified, frequently bearded old men in formal dress. Braatz expected to find customers for his expensive photographs above all in the aristocratic and upper-class circles.

The Parliament

Julius Braatz’s pictures give us insight into the internal life of the German Empire and its constitution anno 1871. According to this constitution of 1871, the Imperial Chancellor (appointed by the Emperor) – Otto von Bismarck was already in office at this time – had to deal with the Bundesrat (upper house) and the Reichstag (parliament), without whose approval no law could be passed. The Reichstag was elected according to a general, equal and secret elective franchise: German men from age 25 on were eligible to vote, and only men could be candidates. This is reflected in Braatz’s photographs, in which almost only men are pictured. The Reichstag had only limited parliamentary rights; its influence on foreign policy and the military budget, for example, was restricted.

Bismarck himself was no friend of parliamentarianism. “The great questions of the day will not be settled by means of speeches and majority decisions – that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849 – but by iron and blood,” he said in 1862 in a speech before the Reichstag.

Bismarck’s tactical manoeuvres and the keen competition between the political parties helped the government to accomplish its aims. In the most extreme situations, the Bundesrat could dissolve the parliament. The Reichstag was, in fact, dissolved four times between 1878 and 1906. In each case, it concerned questions of the military and the defence budget, which were always decided in favour of the government after early elections had been called.

Bismarck’s last day

On 18 May 1889 the Chancellor – who himself was not a member of the Reichstag – held his last speech before the assembly to promote his proposal for a disability and old age insurance plan. It was the third reading of the draft legislation and the debate had already lasted two-and-a-half hours before Bismarck entered the hall to hold his speech, which his adherents then hailed with “vigorous bravos”. Julius Braatz was there at the time because he had just photographed the assembly hall from the press tribune. Unfortunately, none of these photos is in the Bismarck portfolio, but it does contain the photograph of Otto von Bismarck which Braatz took that same day in the foyer after the speech, as well as a portrait of the Chancellor together with his deputy, Secretary of State Karl Heinrich von Bötticher, which was also taken on 18 May. The insurance legislation, by the way, was adopted by a large majority on 24 May 1889. In March of the following year Bismarck was dismissed as Imperial Chancellor by Kaiser Wilhelm II.

How the set came into the photo collection of the Deutsches Historisches Museum

In the same year, 1889, Braatz himself published the results of his photography in the temporary Reichstag building. It is not known how many copies he printed. In addition to the (incomplete) collection in the DHM, there are two further sets, also incomplete. According to the publisher, the large-format, albumen prints on carton are directed at “all classes of the population who are interested in politics”. But the expensive volume remained reserved for the more well-to-do classes. One gilt portfolio was presented to Otto von Bismarck at the end of his tenure. The present set came to the DHM collection from the possessions of the former Imperial Chancellor, where it is now available for exhibitions, but also for research.

Biography

Hermann Julius Braatz was born in Müncheberg in 1844, took part in military interventions, and was discharged from the army as an invalid in 1872. Only two years later he owned three photo ateliers and was entitled to call himself “Court photographer of Prince Friedrich Carl von Prussia”, a title he had earned by making a number of portraits of the prince and which granted him access to the higher circles of society. In 1888 he received permission to photograph the knighting of Prince Heinrich of Prussia in Neumark. This was the beginning of Julius Braatz’s photography of political events, which from that time on was his preferred field of activity.