The Neue Wache – From Guardhouse to National Memorial

Sven Lüken | 11. November 2022

Situated next to the Zeughaus is the Neue Wache, which today serves as Germany’s central memorial to victims of war and tyranny. As we approach Volkstrauertag (Germany’s annual day of remembrance), Sven Lüken, head of the DHM’s Militaria Collection, takes a look back at the building’s history.

In the 18th century, the Schlossbrücke headed westwards from the Berlin Palace and over the stretch of the River Spree known as the Kupfergraben. Back then, a small gateway stood directly at the passage through the bastions of the city fortifications. Later a building was erected here to serve as a base for the palace guard: the Neue Wache (or “New Guardhouse”).

1815: Gentrifying the View

After the demolition of the ramparts began in 1735 and the area at the eastern end of Unter den Linden became the site for monumental prestige projects, the Neue Wache emerged as a point of interest in the new cityscape. The building now formed part of a grand architectural complex that came to be known as the “Forum Fridericianum” in tribute to its royal patron, Frederick the Great. Begun in 1740, the forum includes such notable buildings as the opera house (Staatsoper) and the Palais des Prinzen Heinrich (now the main campus building of Humboldt University). Following their accession to the throne in 1797, Prussia’s new rulers King Friedrich Wilhelm III and Queen Luise took up residence in the Königliches Palais (or “King’s Palace”) directly opposite the Zeughaus. The guards stationed in the Neue Wache were now responsible for their security in the “King’s Palace” (not to be confused with the larger Berlin Palace on the other side of the bridge). The “King’s Palace” is now known as the Kronenprinzpalais – an allusion to its earlier role as the residence of the Prussian crown prince.

Situated directly adjacent to the Zeughaus and opposite the Königliches Palais, the Neue Wache soon attracted the creative attentions of the artistically minded king. After years of deliberation about possible designs, the successful conclusion to the Wars of Liberation relieved Prussian finances sufficiently to fund the construction of a new building. Drawing on ideas originally formulated by the architect Salomo Sachs, it was the legendary Prussian Surveyor-General, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who lent the design its final convincing form, which took two years to construct, from 1816 to 1818.

1818 to 1918: Military Service at a Memorial Site

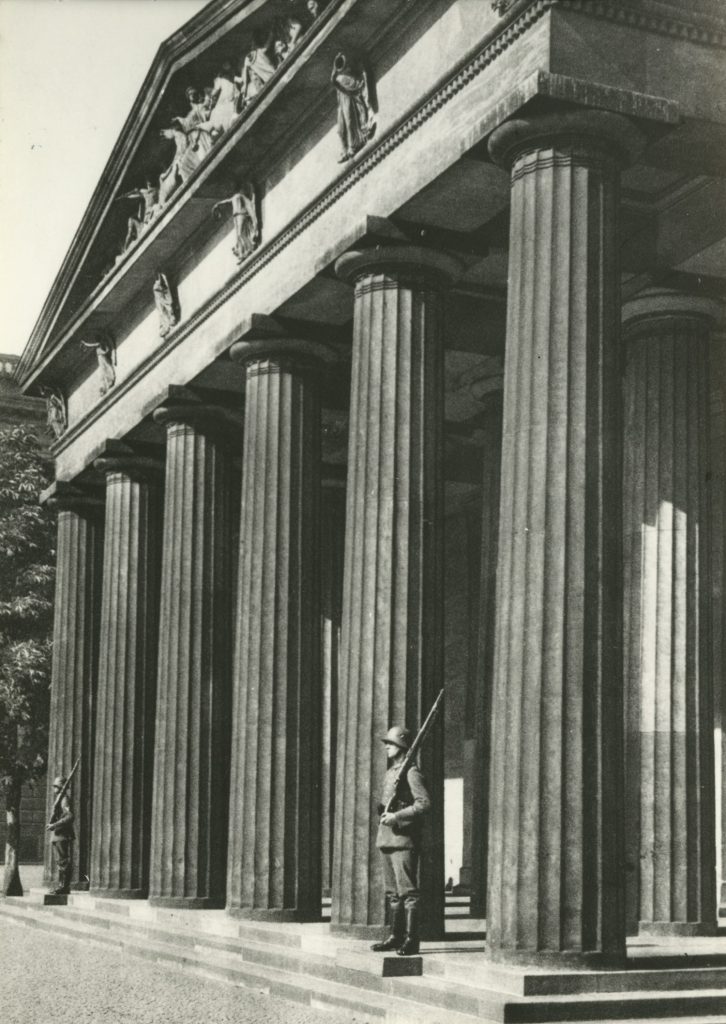

When seen alongside the monumental and severe conservatism of the Berlin Palace’s facade, the cheerful Baroque forms of the Zeughaus with its toy-like trophy adornments, or the opera house’s opulent Corinthian capitals, the austere architectural vocabulary of the Neue Wache’s classical Doric order gives clear expression to the ascetic values associated with the Prussian military. For educated contemporaries, the significance of this style would have been immediately apparent. At the same time, the pared down cuboid forms of Schinkel’s design mark a masterpiece of German Neoclassicism.

The goddesses of victory featured in the Neoclassical frieze by Johann Gottfried Schadow (as well as on the gable relief, a subsequent addition from 1846) are already imbued with a warlike quality by dint of the iron and lead in which they are crafted. The choice of imagery reinforces military values: with scenes of combat, determination, death, and pain in pursuit of victory.

The grandeur of natural stone is reserved for the more prominent parts of the building, while – in common with the Roman constructions on which it is modelled – the remaining portions are of simple brick. Although it is a relatively small structure, Schinkel successfully incorporated features to ensure it would not be overshadowed by the much larger buildings nearby. Gargantuan corner risalits enclose a Doric portico, which looks less like a supporting structure for the Neoclassical gable relief than a row of soldiers guarding a Roman fort in enemy territory. Far from looking hostile, the guarding figures inspire confidence through the protection they afford.

All this effort to create a prestigious guardhouse for a military state. The interior layout, by contrast, assumed a suitably unassuming form consistent with a functional military building. Nothing about the entrance, guardroom, officers’ quarter, and detention cell would have given any cause to suspect that this was in fact where a royal commander would “rope in” (to use the military expression for assembling the guard) a selection of soldiers drawn from the most elite regiments in a kingdom renowned for its military prowess at the time.

The Neue Wache was also a memorial site from its very inception. When plans for the building were completed in 1815, it was intended to commemorate the years of struggle and heavy human toll endured by the Prussian population in the Wars of Liberation against Napoleonic France. Five generals popular with the soldiery and general population alike were immortalized in statues designed by renowned Berlin Neoclassical artists. Their inclusion served to represent the sacrifices of the Prussian army. Two of the figures – Scharnhorst and Bülow – flanked the Neue Wache, while the remaining three – Yorck, Blücher, and Gneisenau – stood opposite on the edge of the Prinzessinnengarten, their poses and gestures echoing those of the figures of Scharnhorst and Bülow. This was long before Unter den Linden became the six-lane rat-run we know today, and so what emerged was a forum for the Prussian army tucked away in a secluded – almost sleepy – spot beneath the tall lime trees that lend the avenue its name.

Daily life at the Neue Wache would have known little variety: unlike today, it was not the setting for protests or publicity stunts, just the unrelenting military rhythm of the hourly changing of the guard. One change did come in 1818 with the introduction of the “Grand Changing of the Guard”, a daily military ceremony complete with marching band. Based on a Russian tradition, this military spectacle remained a Berlin tourist attraction until the dissolution of East Germany in 1990. A small metal fence by the lime trees effectively cordoned the area off from other activities. However, this did not prevent the area from taking centre stage in the events of 16 October 1906, when the impostor known to posterity as the “Captain of Köpenick” (Hauptmann von Köpenick) had his captives, the real mayor of Köpenick and his staff, brought to the Neue Wache for interrogation in a deliberate attempt to achieve notoriety. Later, noting the advantages of the site’s central location, the Prussian military command had its telecommunications and post office moved to the Neue Wache in the run-up to the First World War. It was from here that Germany’s military mobilization was set in motion, heralding the catastrophe that was to come.

1931 to 1945: First World War Memorial

After the revolution of November 1918, Germany dispensed with monarchs and the regiments who guarded them. The Neue Wache no longer served a purpose. Some initial thought was given to the site’s commercial value, and it was only because of the building’s status as a historical monument of considerable artistic merit that it emerged as an obvious candidate early in discussions about the need to establish a central memorial to the victims of the First World War. On the suggestion of Otto Braun (Prussia’s Social Democratic premier) the commission went to the competition-winner, Berlin architect Heinrich Tessenow, a professor at the city’s Technische Hochschule, who was particularly popular in conservative circles. The redesign of the memorial, now known as the “Monument of the Prussian State Government”, was completed in 1931. In accordance with Tessenow’s design, the interior of the building was gutted to create a single solemn memorial space, which was then exposed to the elements by a circular skylight, deliberately opening up the memorial to the changing weather for visual effect. Forming the centre of the monument was a block of black granite, adorned with a silver and gold-leafed oak wreath. This surface was reserved for the laying of remembrance wreaths. The new design made no provision for military guards of honour.

Tassenow’s monumental design also found favour with the Nazi regime after it assumed power in 1933. It was in this period that a simple Christian cross was added to the wall, doubtlessly complementing the design but with symbolism that pointedly excluded the commemoration of non-Christian (particularly Jewish) servicemen. From 12 March 1933, military guards of honour and the ceremonial changing of the guard returned to the Neue Wache, which henceforth assumed the unofficial role as “Reich memorial” in Nazi war propaganda – until, that is, its destruction in the Second World War.

1960 to 1990: A Communist Memorial – Remembering the Victims of Fascism and Militarism

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, there were discussions about what was to become of the building, sullied as it was by its association with Nazism and Prussian militarism. With the approval of the occupying Soviet forces, East Germany’s SED regime eventually began to warm to the idea of revisiting the historical designs of Schinkel and Tessenow. In 1950, East Germany’s leader Walter Ulbricht gave the order for the statues of the Prussian generals from the Wars of Liberation that had formed part of the original design to be either removed or relocated. The Neue Wache itself assumed its new guise as East Germany’s “Memorial to the Victims of Fascism and Militarism” from 1960, and in 1969 Tessenow’s granite block and oak wreath made way for an eternal flame in a prismatic glasswork crucible made from Jena glass. The exposed skylight was also filled in. Soil from concentration camps and battlefields, as well as the mortal remains of unknown prisoners and soldiers (representing those who died resisting Nazism or killed fighting its wars) made the memorial a highly emotive reminder of East Germany’s founding myth and raison d’être as a state. This East German display of pacifism was guarded in curiously militaristic fashion, however: two soldiers stood watch outside – clad now in the field grey of the National People’s Army. Furthermore, the ceremonial changing of the guards became an undeniably popular tourist attraction in East Berlin.

From 1990: Kohl and Kollwitz – The Federal Republic of Germany’s Central Memorial Site for the Victims of War and Tyranny

After the fall of the Berlin Wall paved the way for Germany’s reunification in 1990, Tassenow’s original design was largely restored – this time, as a memorial for the whole country. Only the granite black with the oak wreath, which had in fact been preserved, was felt not to be an appropriate fit for the new memorial. At the request of then-chancellor Helmut Kohl, a (greatly enlarged) copy of Käthe Kollwitz’s sculpture, Mother with Dead Son, was installed on the spot instead. There was a long debate about how best to ensure the site’s legitimacy and relevance, after which accompanying bronze plaques were cast, listing the various groups of victims whose memory was honoured by the memorial. Since 1993, the Neue Wache has served as the “Central Memorial of the Federal Republic of Germany for the Victims of War and Tyranny”. Military ceremonies are limited to special occasions and are conducted by the Bundeswehr in a manner consistent with the German military’s reduced postwar role. It seems that Chancellor Kohl’s instincts were right: today, Käthe Kollwitz’s sculpture is understood by visitors from around the world as an expression of personal loss and suffering.

No Place for Prussian Generals Here

There is a bitter postscript to the story. In return for agreeing to having the original sculpture enlarged, Käthe Kollwitz’s descendants ensured that the five Prussian generals whose figures were an integral part of the very first design would be banished from the Neue Wache until 2015 (when the artist’s copyright would expire). Based on the pronouncements of various figures from academia, the arts, politics, and local government, the common consensus was that the memorial should be restored to its original constellation once the reconstruction of the nearby Berlin Palace was complete. In the meantime, Yorck, Blücher, and Gneisenau remain banished and hidden among the undergrowth at the back of the Prinzessinnengarten. This in itself means that the design has not been faithfully restored. Strangely enough, it was the statue of Scharnhorst, a democratically inclined man of relatively humble origins, and that of the musical, affable, and magnanimous Bülow which were removed entirely from the Neue Wache in 2021. Meanwhile, the swashbuckling aristocrat Blücher and the reactionary Yorck were permitted to stay put. Which just goes to show that the best of intentions can always backfire!

|

Foto: DHM/Thomas Bruns |

Sven LükenSven Lüken is head of the Militaria Collection at the Deutsches Historisches Museum |