1,200 signatures and a light wheeled tank behind the GDR Embassy

Rolf Brockschmidt | 22. November 2023

When Wolf Biermann was ousted from the GDR in 1976, Rolf Brockschmidt was studying at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. There, too, the expatriation triggered a general outcry. Together with other students, he spontaneously founded the committee “Biermann blijft DDR-Staatsburger”. In this DHM blog Rolf Brockschmidt writes about their active engagement and the attempt to submit a petition to the GDR Embassy.

Biermann has been ousted! The news struck us like a bomb. Crisis meeting under the roof of the German Studies Institute of the Rijksuniversiteit te Utrecht. Gregor Laschen, docent and poet, gathered a handful of students together in his room. In their presence he rang up the civil rights activist Robert Havemann. Havemann leaned out of his window in East Berlin and reported that the Volkspolizei, the “People’s Police”, were standing in front of Biermann’s house. We had the feeling of being right there live at this historic moment. Laschen and we students spontaneously founded the committee “Biermann blijft DDR-Staatsburger” (Biermann remains a GDR citizen), in which I participated. In 1976, I was at the Utrecht University for a year to study Dutch and German language and literature.

Gregor Laschen had good connections and had just used his contacts to help a group of students to publish the second edition of an anthology of German-language literature containing previously unpublished texts. Biermann had been represented in the first edition (May 1976) with his poem “Ballad of the Prussian Icarus”. He sang the song at his legendary concert in Cologne on 13 November 1976, shortly before he was expatriated.

The outrage among Dutch intellectuals was great, a number of whom, like Biermann himself, were flirting with an idea from 1975 about having a kind of Eurocommunism that sought a path to a democratic socialism beyond Soviet state communism. The GDR found this idea more than questionable.

For us it was about gathering as many signatures for a petition against Biermann’s expulsion as possible. The committee saw in the deprivation of his citizenship “a serious violation of human rights”, as could later be read in the Dutch daily newspaper “de Volkskrant”.

The “hard core” of the committee consisted of some ten persons, and we tried to convince our fellow students to sign the petition – which wasn’t easy, because Dutch students were nowhere nearly as politicised as their West Berlin counterparts.

“To categorise Wolf Biermann as an enemy of East Germany is false, given his clearly positive pronouncements in his songs and texts,” it stated in the petition, which was supposed to be delivered to the GDR Embassy in Andries Bickerweg in The Hague.

Not everyone was as naïve about the matter. The first ambassador of the Netherlands in the GDR, K.W. Reinink, described Biermann as the “Don Quixote of the GDR cultural scene” who goes to bat “for a GDR that doesn’t exist and also cannot exist,” as Jacco Pekelder, director of the Netherlands Institute in Münster, quotes the ambassador in his book “Die Niederlande und die DDR. Bildformungen und Beziehungen 1949-1989”1.

At a time when occupational bans reigned supreme in the Federal Republic of Germany, people in intellectual circles in the Netherlands would like to have seen the GDR as the true antifascist German state. The fact that this supposedly better half of the German states, of all places, had now taken such strong action against leftist critics met with strong condemnation.

Our Biermann committee had notified the GDR Embassy that we would personally hand over the petition with 1,200 signatures on 8 December 1976. In front of the embassy, ten policemen in blue uniforms, some with leather jackets and visored caps, awaited us. They were sitting in Mercedes limousines. For West Berlin eyes this was quite a civilised reception.

When we ten participants in the action wanted to get to the embassy, the officer-in-charge asked whether this was a demonstration. None such had been registered. If, however, this is in fact a demonstration, it is herewith authorised, he said. “That’s the way we do things in The Hague.” I remember this sentence. I stayed a bit on the side, wore sunglasses and a scarf around my mouth, because I was going to take the transit train to West Berlin and had to pass through the GDR.

In the meantime we noticed hectic activities behind the curtains on the upstairs floor of embassy. Cameras were put in place. The policeman requested us to line up on the opposite pavement, where we unfurled a large banner on which was clearly written: “Biermann blijft DDR-Staatsburger”. Our group smiled and waved in the direction of the GDR photographers behind the curtains.

A couple of us approached the gate of the embassy and rang the bell. Someone told us through the intercom system that the embassy was closed and they would not accept the signatures. From the opening hours posted on the brass plaque, one could, however, infer that the embassy was indeed supposed to be open. A reporter from the left-wing radio station VARA had accompanied us and held his microphone to the intercom. But the embassy personnel refused to accept the petition. So our envelop then landed in the letterbox. When we went back to the cars, we discovered a light wheeled tank of the Hague police behind the embassy. Just in case. It was apparently not quite as harmless as it had seemed. The GDR Embassy had evidently felt threatened. The results of the action: three reports on radio and television and a short article in the newspaper “de Volkskrant” headlined “Embassy refuses to accept signatures for Biermann”2.

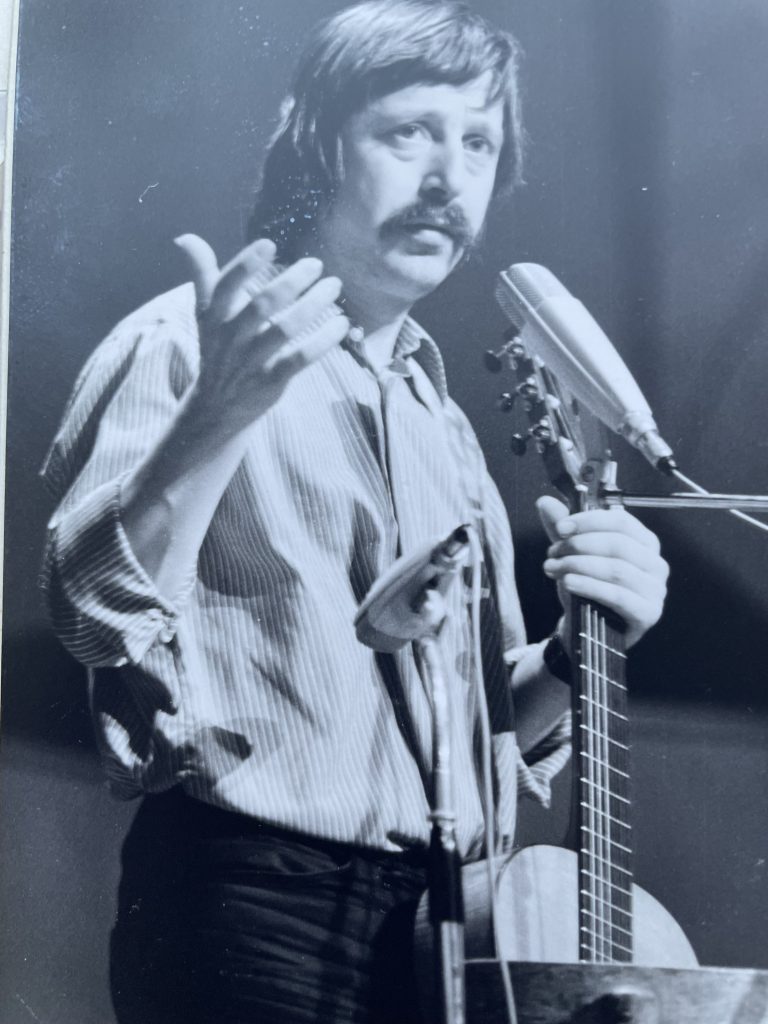

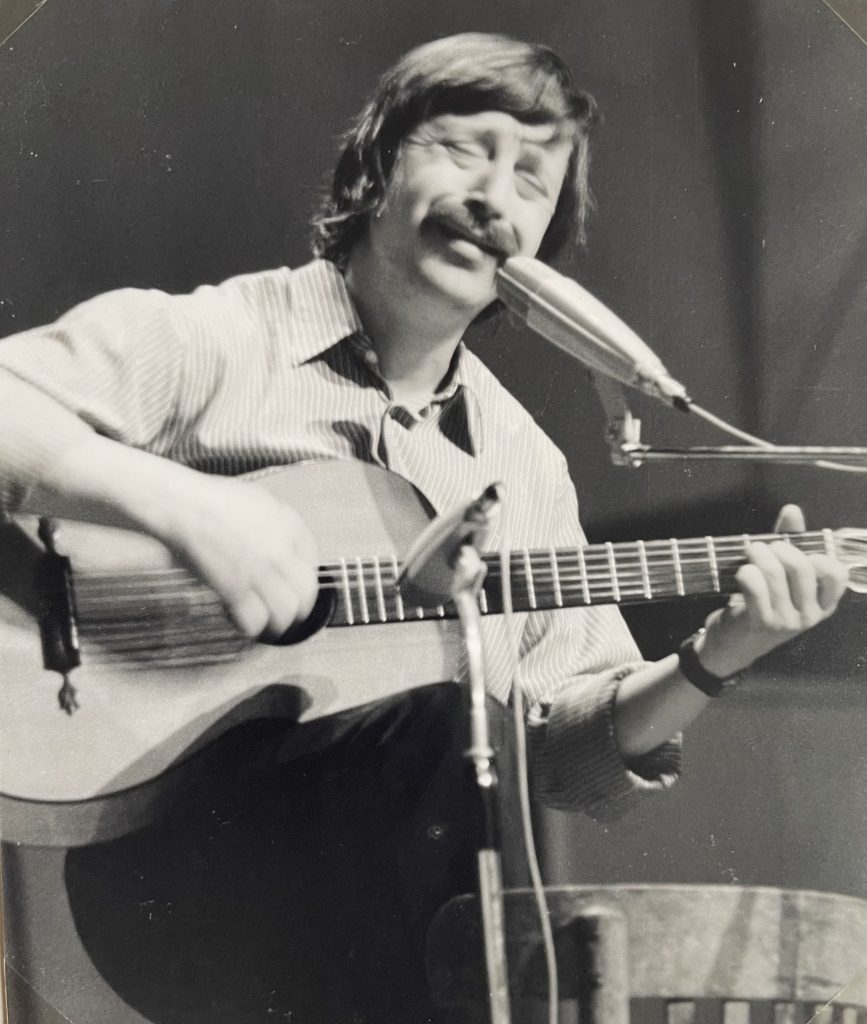

Wolf Biermann, for his part, had decided after the Cologne shock not to give his next concerts in the Federal Republic, but rather in the Netherlands. On 27 February 1977, our student group travelled at the expense of the Goethe Institute by bus to Nijmegen, where Biermann was performing. I remember a full house in the big concert hall. Biermann entered with his guitar, sat down at the piano and played his songs, including the “Prussian Icarus”. He moderated the show himself, reacted to calls from the audience, remained snappish and witty, did not hold back with his criticism, neither against the West nor the East. The people were hanging on his every word. Even in the intermission he stayed on stage and debated intensely with the audience. I stood the whole time just before the stage and took photographs. After four-and-a-half hours – it was long after midnight – there was thunderous applause and standing ovations. Biermann clearly seemed exhausted, but happy. A memorable evening on neutral ground.

Wolf Biermann at his first concert on 27 February 1977 in Nijmegen after his expatriation. Foto: Rolf Brockschmidt

Biermann gave his all at the concert, Nijmegen 27 February 1977. Foto: Rolf Brockschmidt

Wolf Biermann in dialogue with the audience. Nijmegen, 27 February 1977. Foto: Rolf Brockschmidt

1 Jacco Pekelder: Die Niederlande und die DDR. Bildformung und Beziehungen, 1949-1989. Münster 2002, https://www.uni-muenster.de/NiederlandeNet/nl-wissen/geschichte/ddr/biermann.html

2 „Ambassade weigert handtekeningen voor Wolf Biermann“, de Volkskrant, 9 December 1976.

|

|

Rolf BrockschmidtRolf Brockschmidt studied German, Dutch and history at the Free University Berlin and the Rijksuniversiteit te Utrecht. From 1977-1981 he worked from West Berlin as a freelance reporter for the Dutch programme of the Deutchlandfunk. From 1982-2018, after completing a traineeship, he worked as an editor for the Berlin Tagesspiegel, for which he now writes as a freelance journalist. |