From Bayeux to the Bastille: The fortress key as a sign of peace and revolution

Sven Lüken | 2 April 2025

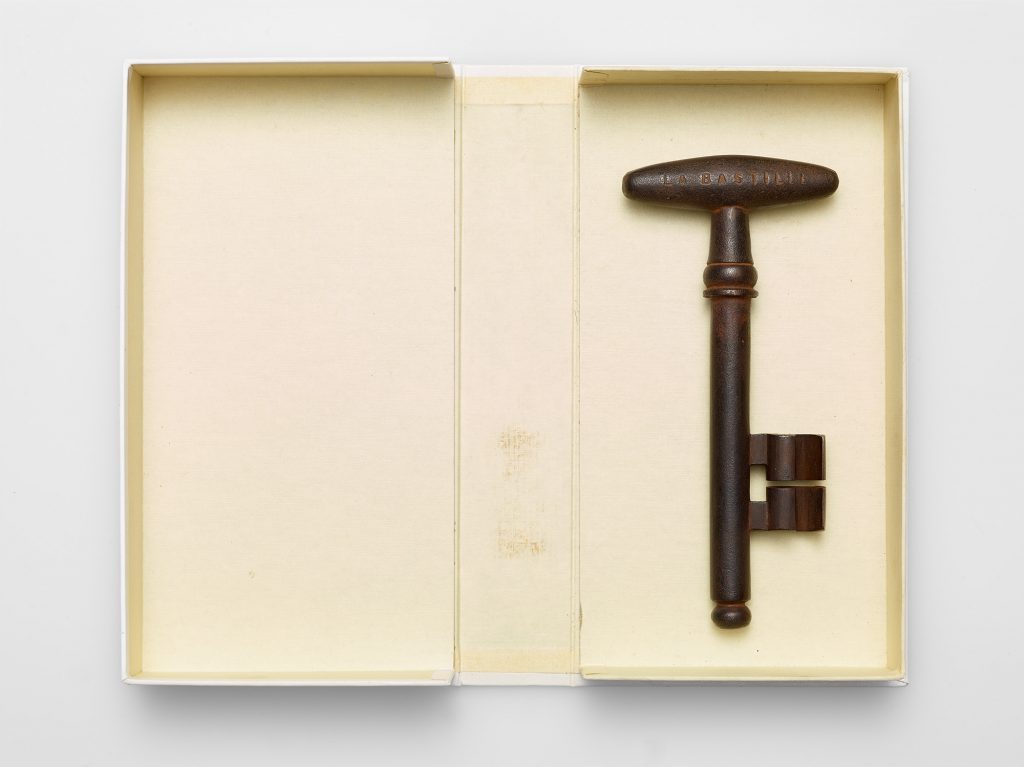

When the Bastille was stormed by the citizens of Paris on 14 July 1789, La Fayette, the commander of the National Guard, was given the key to the fortress. A reproduction of the key was displayed in the exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th Century” and other fortress keys are in the collection of the Deutsches Historisches Museum. Sven Lüken, head of the DHM’s Militaria collection, explains the historical significance of these objects.

Many things are stored in the depot of the Deutsches Historisches Museum – simply because they are still there and have an inventory number, even though it’s not clear just now how they should be used. That’s very common in museums. There is also a metal cabinet with a whole tray full of neatly lined-up keys, around 60 altogether.

The documentation about them, like some of the keys, went missing in the Second World War, but there are old inventories. According to these lists, the keys that were lost were primarily from the gates of northern French cities and fortresses that were forced to capitulate in the course of the hostilities between Prussia and France in 1870/71. By that time, the Prussian army, founded in 1701, had already captured many fortresses. And hadn’t the Great Prussian Friedrich pried open various fortress doors in Silesia as well? But nothing was left of all that, because in 1760 the Austrian and Russian troops, and in 1806 Napoleon’s Grande Armée, plundered the Zeughaus. Other military museums, like the Army Museum in Paris, were spared this fate at the time. After the assaults on Berlin in the 18th century, the Prussians became involved in the war against Denmark. In 1864, they carried off the keys to the captured Fredericia fortress in Jutland, and after 1870, they seized one French fortress after the other. Most of the keys in the DHM collection came from this conflict, which shows how important these victories were for Prussia’s self-perception. This became evident above all in the Second Empire.

What kind of custom, still known today, is it when on Weiberfastnacht (Women’s Carnival) the keys to cities on the Rhein, the carnival heartland, are temporarily passed into the hands of the fools?

Since ancient times, fortune in European wars has been sought not only on the open battlefield. Until the Early Modern Age, the siege of cities, castles and fortresses was a major element of war. Poliorcetics is the technical term for siege warfare, and it could almost be called a science. The fortifications, like the siege engines developed to attack them, were constantly improved. A huge leap forward came in the 14th century with the introduction of siege artillery based on the invention of gunpowder. Whereas it was first the loud blast of the shot that spread fear, bronze-cast cannons perfectioned the aim of the artillery, so that by the end of the 18th century it was possible to calculate precisely when a fortress was ready to be stormed and when it would capitulate.

The knowledge, the expectations of the participants, and their social and moral aptitude did not mature to the same extent. In antiquity and the Middle Ages, it was expected that captured fortresses would be looted by the conquerors, not seldom accompanied by incredible atrocities. The victors wanted to crush and humiliate the opponent. No holds were barred. In the Middle Ages, a key activity in war was to burn down entire villages and carry away the livestock, decimating whole stretches of land. The end of the chivalrous feudal armies and the introduction wayward mercenaries around 1500 left no alternative. With the maxim “War feeds itself”, Wallenstein’s Landsknecht army in the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) demanded the possessions of the enemy as the wages of war. Plundering was in the genes of all armies in the Early Modern Age. In the second half of the 17th century, once flourishing Central Europe was marked by entire areas that had been ruined by war for centuries to come.

Very slowly, concepts of humanism and enlightenment gained credibility that proposed limiting warfare to the immediate participants in it. Christianity and Church had always preached generosity of spirit, which was occasionally shown. But it was only in the time of the princely armies of the 17th century that a different mindset gained ground, realising that it was not necessary to decimate a defeated enemy, for there were other ways that the victor could make use of them.

Some armies developed an understanding of martial law that upheld “self-discipline” as a standard and forbade looting as it had previously been done with captured fortresses. Anarchistic mercenary troops were then sometimes turned into well-drilled princely armies consisting of professional soldiers. And they enforced the laws of war to discipline their own troops. The professional armies of the princes in the Early Modern Age were not distracted by looting and thus became more effective as warriors. Many a princely commander in those days could be proud of the enhanced prestige gained through the additional economic benefit of a captured, but unscathed town.

And so it came that fortresses and fortified cities were gradually able to get away without being pillaged as long as they capitulated as demanded. This required communication between the besieger and the besieged, which was difficult, because it was precisely this communication with the enemy that was normally prevented. Still familiar are parliamentarians who used to negotiate between the different parties with a “white flag” in hand. In the earlier times a different utensil was used to send such messages – namely, the key to the fortress.

The walls of a fortified city could only be overcome at the open or closed gates of the city. The walls divided the city from the land, the rights of the city from the rights of the land, so that the city gates were of great importance. The coat of arms was displayed at the entrance and announced who was in charge.

The keys to these gates were not like today’s little security keys but were similar to church keys. It seemed obvious to use these keys to communicate, to offer them to the enemy, and thus to declare one’s own city an “open” city. There are numerous examples in art history that show the key in the setting of a siege. The carpet of Bayeux from 1077, which depicts the conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066 and his previous activities in northern France, shows how the siege of Dinan was ended when the besieged defenders of the French castle held out a pair of keys on a spear. But the best-known depiction of the handover of keys is that by the Spanish artist Diego Velázquez, who shows the Dutch stadtholder of Breda, van Nassau, coming forward to surrender the key to the city to the Spanish general Ambrosio Spinola in 1625. Although the Spanish soldiers are ready to plunder the town, it doesn’t happen: the transfer of the key prevents the storming of Breda and contains the violence.

This was completely different from what happened in the northern German Protestant stronghold of Magdeburg in 1631, when soldiers of the Catholic League sacked the city and looted it for three days, with all the consequences involved in the defeat. The city was not surrendered, but taken by storm, showing a clear connection between the transfer of keys and pillaging.

In the 18th century, the transfer of keys apparently became the rule. Beginning in 1787 in the Austrian Netherlands, a conservative section of the bourgeoisie that demanded a return to old traditional rights rose up against the centralist, enlightened state government of the House of Hapsburg. In 1789, a small rebel conservative army that had formed in Brussels crossed into the surrounding Duchy of Brabant, but the Austrian army crushed the revolt in the bud, so that the rebels capitulated in December 1790 – far from the gates of Brussels but with a transfer of the keys, this time presented in style on a tray.

It could have ended in a different way. On 14 July 1789, the citizens of Paris stormed the Bastille, a bastion of the city fortifications that had served for decades to incarcerate the enlightened with no hope of release. Unexpectedly, there were hardly any prisoners left. The commander and his auxiliaries capitulated and surrendered the keys to the fortress, but it didn’t help them – the auxiliaries were lynched, the commander beheaded, and the fortress demolished. The keys ended in the hands of deserving officers, among them the Marquis de Lafayette, who had fought as a French soldier at the side of General George Washington for the freedom of America in the War of Independence. The enlightened political philosopher Thomas Paine arranged to give Lafayette’s key to George Washington to be kept at his country estate as a souvenir of the struggle for independence. The significance of the fortress key underwent a change: from a document of military victory to a souvenir of the event.

In the Middle Ages, fortress keys were handed over to the new owners. In the Modern Age the keys to besieged fortresses were presented to the victor with great ceremony, a practice that continued into the 19th century. For the participating soldiers the keys were documents of victory, for which they generously refrained from carrying out the customary rights of victors. The victorious besieger received the keys and passed them on to another place where they were preserved and sometimes displayed. Documents of victory became souvenirs. In France such documents were held in the Army Museum at Les Invalides, in Prussia it was at the Zeughaus on Unter den Linden.

|

|

Dr. Sven LükenDr. Sven Lüken ist Sammlungsleiter Militaria am Deutschen Historischen Museum. |