Beyond black and white: Tracing colours of postwar exhibitions

Maciej Gugała | 13 August 2025

Shortly before the opening of our exhibition On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948 at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, a friend of mine told me she would not visit. The reason was not the subject – postwar exhibitions about the German occupation of Europe – but the fact that the show included black-and-white photographs and films. “They always put me in a depressive mood”, she said, “no matter what they show”.

For her, black-and-white imagery is more than just a visual style. It instantly evokes the Second World War and the Holocaust because that is how she first encountered those events at school: through black-and-white photographs. Her reaction might seem surprising at first, but it points to something deeper – the emotional power of visual codes in shaping how we remember the past.

Colour is one such code. In our visual culture, black-and-white photography has become shorthand for “the historical”. This is all the more striking given that photography – a medium of 200 years old – is much younger than other, colour-rich forms like painting, which have accompanied humanity since prehistoric times.

And yet it is black-and-white photography that often connotes seriousness, authenticity, and archival authority. This likely stems from its early use, when its distinct visual precision was inseparable from a limited colour palette – and from the fact that it documented events that now feel temporally distant, inaccessible, and often beyond the reach of living witnesses. It is no coincidence that some contemporary films are shot in black and white: the aesthetic alone can transport us into the past.

But the power of black-and-white imagery is not purely affirmative. Its emotional charge is also ambivalent and can pull in very different directions, even opposite to the reaction my friend described. As the American author Susan Sontag argued, black-and-white photography can neutralise horror, making it more bearable, even beautiful. The same visual codes that evoke gravity and historical significance may also aestheticise suffering or create emotional distance from it.[i]

While working on the exhibition On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948, we – the exhibition team – were aware of these implications. With only black-and-white photographic documentation of past exhibitions at our disposal, we sought a visual language that would resist easy aestheticisation and avoid presenting our narrative in literal black and white.

What helped us was the awareness of a paradox: the original postwar exhibitions on the German occupation had been rich in colour and – despite the gravity of their subjects – often eschewed the muted, standardised tones typical of many of today’s presentations of war, occupation, and the Holocaust.

Recovering the colours of these postwar exhibitions is not just a matter of scholarly reconstruction. It opens a window onto the visual strategies used to represent occupation and violence in the immediate aftermath of the war. It also reveals the expressive range and creativity of designers at the time – often working with modest means – and invites comparison with today’s more standardised exhibition aesthetics.

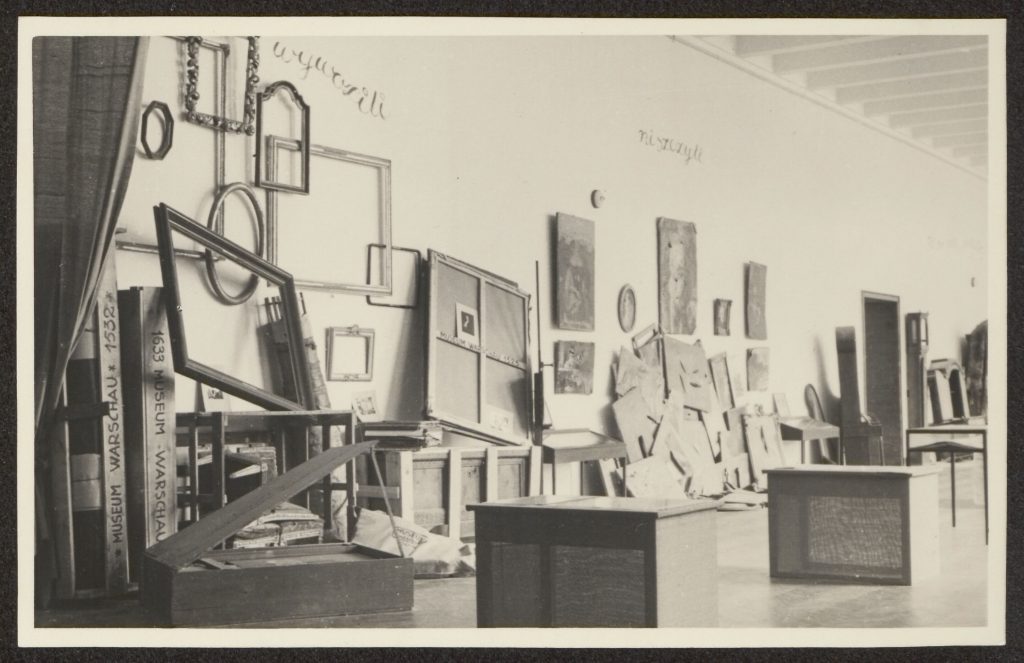

Sometimes, one must rely on imagination. A striking example appears in black-and-white photographs from 1946, taken at the Památník nacistického barbarství (Memorial to Nazi Barbarism) in Liberec. They show reconstructions of prison walls and an execution site from a former Gestapo facility, installed on the memorial grounds, which had once been a garden. The natural greenery surrounding the reconstructions formed an integral part of the exhibition.

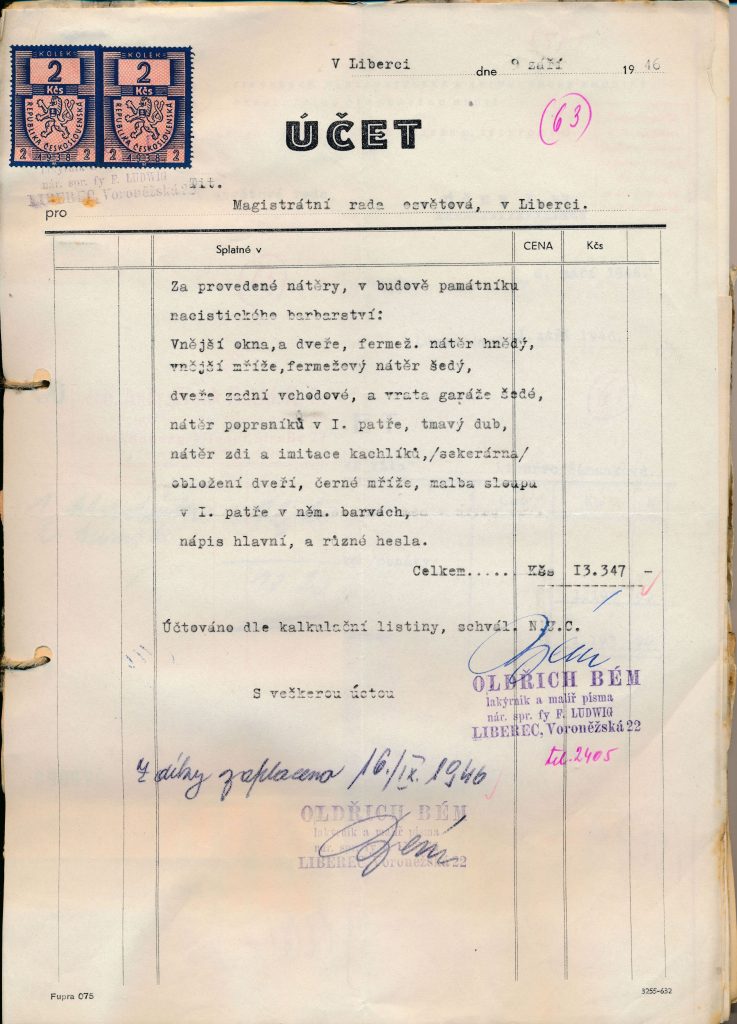

But in some cases, evidence for those colours survives beyond what imagination can offer. Certain sources allow us to identify the colour schemes of historical exhibitions – even if only in fragmentary form. One such source is the budgets and invoices related to the construction of the exhibition in Liberec. In an invoice dated 9 September 1946, the painter Oldřich Bém itemised the painting work done to adapt the memorial building – formerly a residential house – for exhibition purposes:

“External windows and doors, coated with linseed oil paint, brown; external grating, coated with linseed oil paint, grey; back entrance door and garage door painted grey; painting of the balustrades on the first floor, dark oak; … door panels, black grating; painting of the pillar on the first floor in the German colours”.[ii] [The “German colours” most likely refer to the national colours of Nazi Germany – red, white, and black.]

Occasionally, information about the use of colour in the postwar exhibitions we present can be found in the press of the time. In a May 1945 review of the exhibition Warszawa oskarża (Warsaw Accuses) at the National Museum in Warsaw, a journalist for the Polish monthly Polska Zbrojna wrote of “the solemn silence of the white rooms”[iii] and, describing a reconstructed execution site in one of the exhibition spaces, noted “a piece of wall chipped by bullets, stained with splashes of blood”.[iv]

Curatorial documentation can also contain valuable information about the use of colour in exhibitions. In the 1945 “exhibition diary” for Warszawa oskarża, the organisers mentioned, for example, a symbolic installation titled The Reviving Trunk, “lit in red”[v]; curatorial texts placed in niches “on a black background”[vi]; and “a red flag with a white eagle”[vii] (the eagle being a symbol of Poland) draped over an urn containing the ashes of burned historic books.

Both source materials and scholarly studies provide a description of the design and colours originally featured in the exhibition poster – which today survives only in black-and-white photographs – pointing to the use of Polish national colours: “Three white crosses on an oval red background, surrounded by a wreath of laurel and oak branches, tied with a red ribbon bearing a white inscription…”[viii]

The documentation for Warszawa oskarża also includes a complete list of exhibits, along with details about their original colours. This highlights another key source of information about historical exhibition colour schemes: the displayed objects themselves. Their colours were not merely decorative but helped shape the overall aesthetic of the display and influenced how visitors perceived and emotionally engaged with it. In the case of Warszawa oskarża, both the original colours of the objects (e.g. “sarcophagus lid made of white polychromed wood”[ix], “wall clock, bronze-gilt, with black figures”[x], “olive-green tailcoat”[xi],) and secondary alterations caused by destruction during the German occupation (“red streaks running down the painting”[xii]), as recorded in the “exhibition diary,” are of particular significance.

Yet beyond such records, it is direct access to the original objects that offers the most immediate impression of the colours once present in historical exhibitions. Although the colours of some objects have changed over time due to ageing, conservation treatments, or lack thereof, encountering them in person reveals how diverse in terms of colour some of those postwar exhibitions must have been.

One example is the exhibition Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka (Martyrology and Struggle), which opened in 1948 at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. Some objects from that exhibition were also included in On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948, such as a tapestry from the Łódź ghetto or a model of a bunker that had served as a shelter for the Warsaw Ghetto fighters. Both are notable for their intense colours – an aspect that surprised many visitors to our show, especially when contrasted with the black-and-white photographs of the same items taken nearly eighty years earlier at the 1948 display.

Many other objects from the Łódź ghetto shown in 1948 – especially paintings documenting the lives of Jews imprisoned there – were again presented by the Jewish Historical Institute in 2024 in the exhibition Uchwycić getto (Capturing the Ghetto). Its curator, Dr. Zofia Trębacz, remarked in an interview recorded especially for On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948 that these colourful works help break through the monochrome image of ghetto life that has taken hold in collective memory through black-and-white photography.[xiii] And, for our exhibition team, familiarity with these works is of particular value, as it deepens our understanding of the visual layer of the 1948 show.

However, our own display had to develop its own colour language. The designers, Marie-Luise Uhle and Hans Hagemeister, structured the space using white panels on which most of the images –predominantly black and white – and texts were mounted, bringing the archival materials to the forefront. To create visual balance and avoid a monotonous colour scheme, they introduced selective colour interventions inspired by original objects. Each chapter of the exhibition was given a distinct visual identity: coloured inserts appeared in the spaces between panels, echoing the hues of the original artefacts featured in that chapter — and connected to the historical exhibition it referenced.

On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948 includes a range of colours – both through the work of our designers and in the objects we displayed or reproduced. However, this did not help my friend, whose unease with black-and-white material I described at the beginning, to move past it. Still, I believe her response was a valuable one. It served as a reminder that the power of visual codes lies as much in personal experience and historical context, as in creative interpretation.

Tracing and rethinking the colours of past exhibitions is not about offering a corrective or asserting a more ‘authentic’ vision. Rather, it is a way of widening the field of view, drawing attention to the plurality of visual strategies once used to represent violence, and to the ways these strategies continue to inform how we see the past today. If black and white has taught us to read certain images in a particular register, colour invites us to look again.

[i] Sontag discusses black-and-white photography and the aestheticisation of suffering primarily in Chapter 5 of her essay collection Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2003), pp. 74–94.

[ii] Účet pro: Magistrátní rada osvětová v Liberci (Invoice for the Municipal Educational Council in Liberec), 9 September 1946, State Regional Archive in Liberec.

[iii] Author unknown, “Warszawa oskarża”, in Polska Zbrojna, no. 100, 25 May 1945, quoted in Wykaz prasy informującej o wystawie “Warszawa oskarża” – 1945 (List of press reports on the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża” – 1945), in Materiały archiwalne dot. wystawy “Warszawa oskarża” (Archival materials on the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża”), file AMNW 1070c, p. 26, Archive of the National Museum in Warsaw.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Wystawa “Warszawa oskarża” – Pamiętnik (Exhibition “Warszawa oskarża” – Diary), 3 May 1945, in Materiały archiwalne dot. wystawy “Warszawa oskarża” (Archival materials on the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża”), file AMNW 1070d, p. 4, Archive of the National Museum in Warsaw.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Dariusz Kaczmarzyk, “Pamiętnik wystawy ‘Warszawa oskarża’ 3 maja 1945–28 stycznia 1946 w Muzeum Narodowym w Warszawie” (Diary of the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża” 3 May 1945–28 January 1946 at the National Museum in Warsaw), in Rocznik Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, no. 20 (1976), p. 599.

[ix] Wystawa “Warszawa oskarża” – Pamiętnik, op. cit., p. 18.

[x] Ibid., p. 37.

[xi] Ibid., p. 39

[xii] Ibid., p. 7.

[xiii] Interview with Zofia Trębacz, filmed 26 February 2025, for the exhibition On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe 1945–1948, Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin, 2025.

|

|

Maciej GugałaDr. Maciej Gugała is a research associate for the exhibition “On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948” at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |