“Ghetto Luck”: A Kilim from the Łódź Ghetto

Dr. Zofia Trębacz | 17 September 2025

The exhibition “On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945–1948” features many extraordinary artefacts. Among these, a kilim – a flat-woven tapestry – from the Łódź ghetto holds a special place, as Dr. Zofia Trębacz from the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute Warsaw describes in her article. The object is on public display for the first time in several decades.

How the kilim wound up in the collection of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw (where it remains to this day) is a mystery. It was first mentioned in connection with the opening of the Jewish Historical Institute’s Museum of Martyrology and Struggle on 18 April 1948, when it was shown as part of the exhibition “Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka” (Martyrology and Struggle).

These photographs suggest that the item came from the collection of the Central Jewish Historical Commission, affiliated with the Central Committee of Jews in Poland. The Historical Commission was founded in August 1944 in Lublin and in the autumn of that year became the Central Jewish Historical Commission.[1] It moved to Łódź in March 1945. Its main task was to document crimes against the Jews. It supplied evidence for the trials of war criminals in Poland and in Nuremberg. Its members also conducted academic research and published critical editions of sources. They also collected archival materials from the ghettos and camps, documents produced by Jewish Councils, occupation-era offices, institutions and private individuals as well as records of pre-war Jewish religious communities. The Commission had branches in several cities. In 1947, the Board of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland made the decision to turn the Commission into the Jewish Historical Institute, based at 5 Tłomackie Street in Warsaw in the rebuilt edifice of the pre-war Institute for Jewish Studies and Main Judaic Library. From 2009, the Institute has been named after Emmanuel Ringelblum, historian and activist, the creator of the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archive (also known as the Ringelblum Archive), murdered by the Germans in March 1944.[2]

The interests of the Commission staff ranged far and wide so that all sorts of documents and artefacts created by Jews during the war found their way into its collection. A large proportion of these were objects found in the former Łódź ghetto – paintings and sculptures, as well as items made for civilian and military purposes for Nazi Germany. The kilim was probably among those found objects.

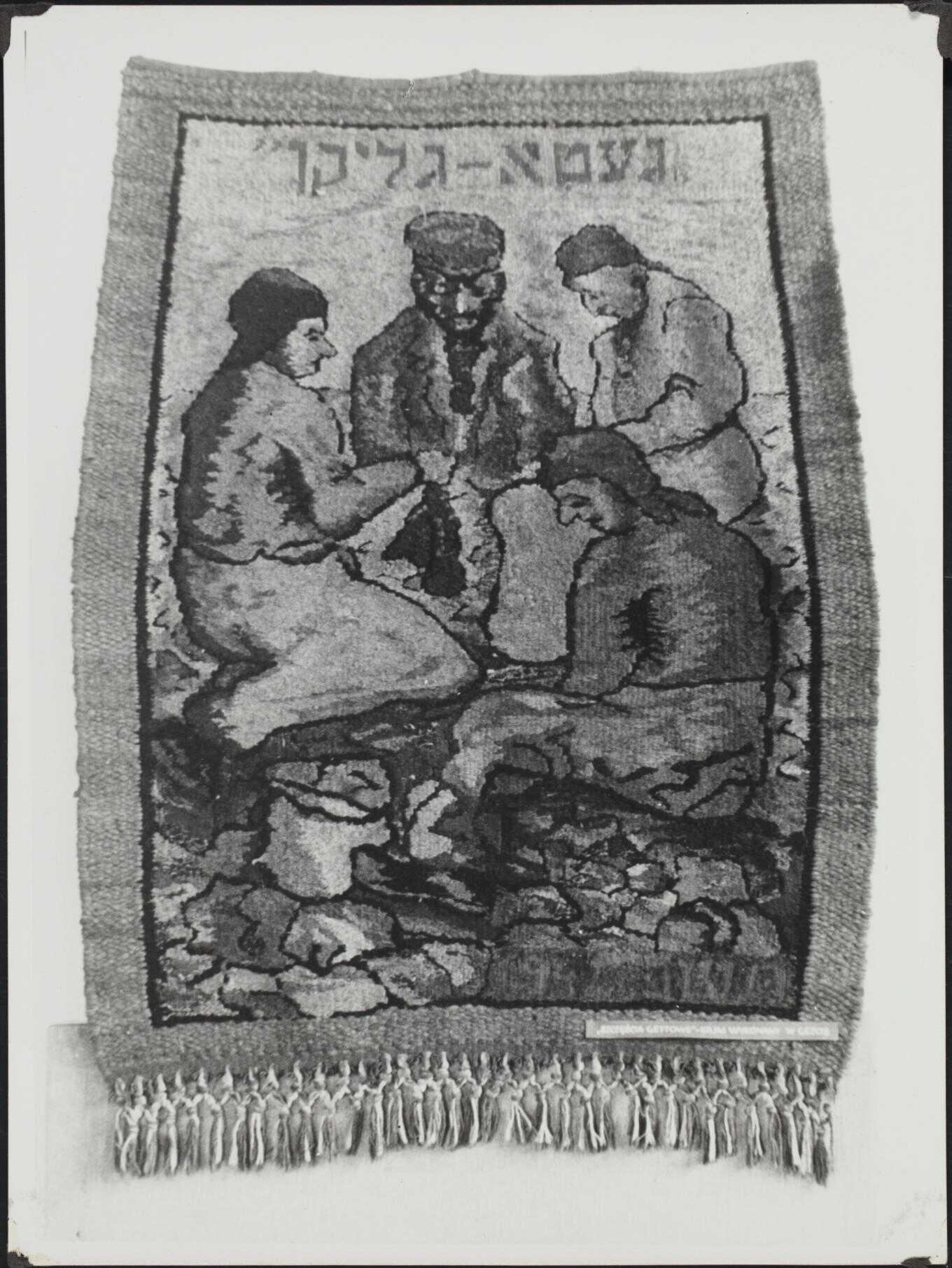

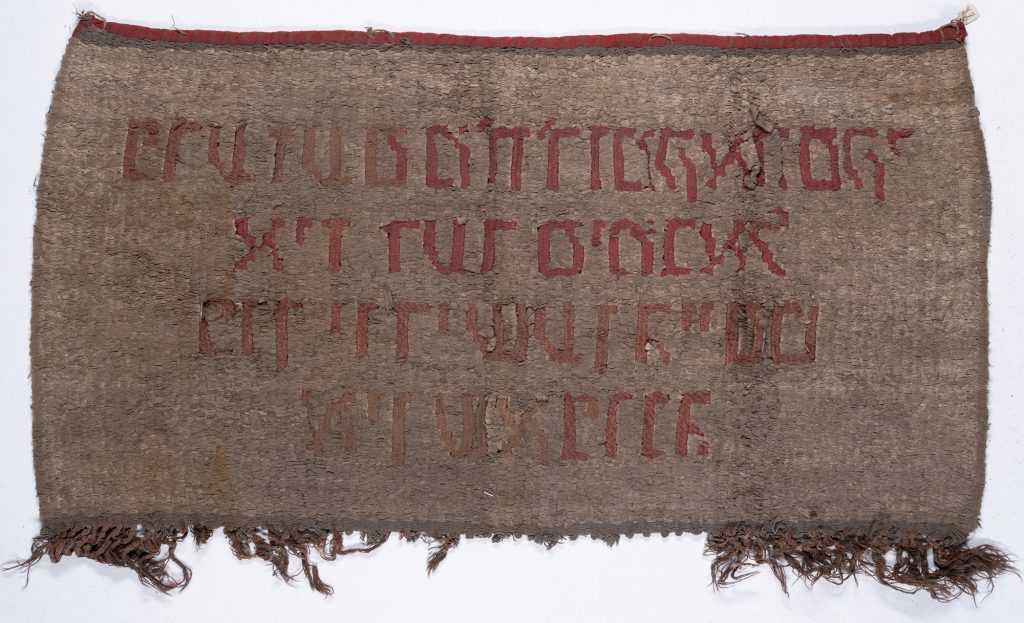

It was made in the Łódź ghetto Carpet Department. It measures 110 cm by 160 cm. The central part shows a scene after a work by Józef Kowner: the figures of four Jews – three women wearing kerchiefs and a man in a hat. They are immersed in work, sitting and squatting in a circle on a cobbled street. The kilim is woven from strips and scraps of fabric on warps made of gray cords. The multi-coloured central field is framed by a thin black border and a wide grey one. The tassels are made of grey and white cords tied to the main body. In the lower part of the kilim is the date 1942 in Arabic and Hebrew digits. The upper part features the ironic title in Yiddish: geto-glikn, “ghetto luck”.

Despite extremely difficult living conditions, ghetto life was not bereft of humour. One can see it as a way of adapting to the harsh reality and coming to terms with it. Nonetheless, for the chroniclers of ghetto life humorous sayings and jokes, some of which can only be understood in context, were astonishing and noteworthy. In this particular case, the juxtaposition of the caption “ghetto luck” with an illustration of Jews working for the German occupiers can be read as an ironic reversal. For here, forced labour benefitting the enemy suddenly becomes a way of saving oneself. Working in a factory or workshop was the first thing that ensured that one would not be deported to a death camp.

There were many different divisions and departments (resorty) in the Łódź ghetto, that is factories and workshops which produced goods for the German economy. Throughout the whole ghetto period, 27 to 32 departments were in operation, employing 13,000–14,000 staff.[3] The Łódź ghetto eventually became a labour camp, and the slogan coined by the head of the Jewish administration, Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, said: “Work is our only way”. This strategy, adopted already in 1940, was developed further over the following years. The resorty in the Łódź ghetto embodied the idea of survival through work. By producing goods for the German economy, they were supposed to champion Jewish usefulness. Those who found employment in them included artists, who made propaganda albums for special occasions, depicting the work of the departments in the best light possible. One such item was a memorial album made for the Carpet Department, overseen by Szyja (Jehoszua) Klugman. It survived the war and is part of the collection of the Jewish Historical Institute. It traces the evolution of the department from June 1941 until October 1943 and features the patterns used on kilims displayed in an exhibition in the Łódź ghetto organised by the Department on 26 December 1942.

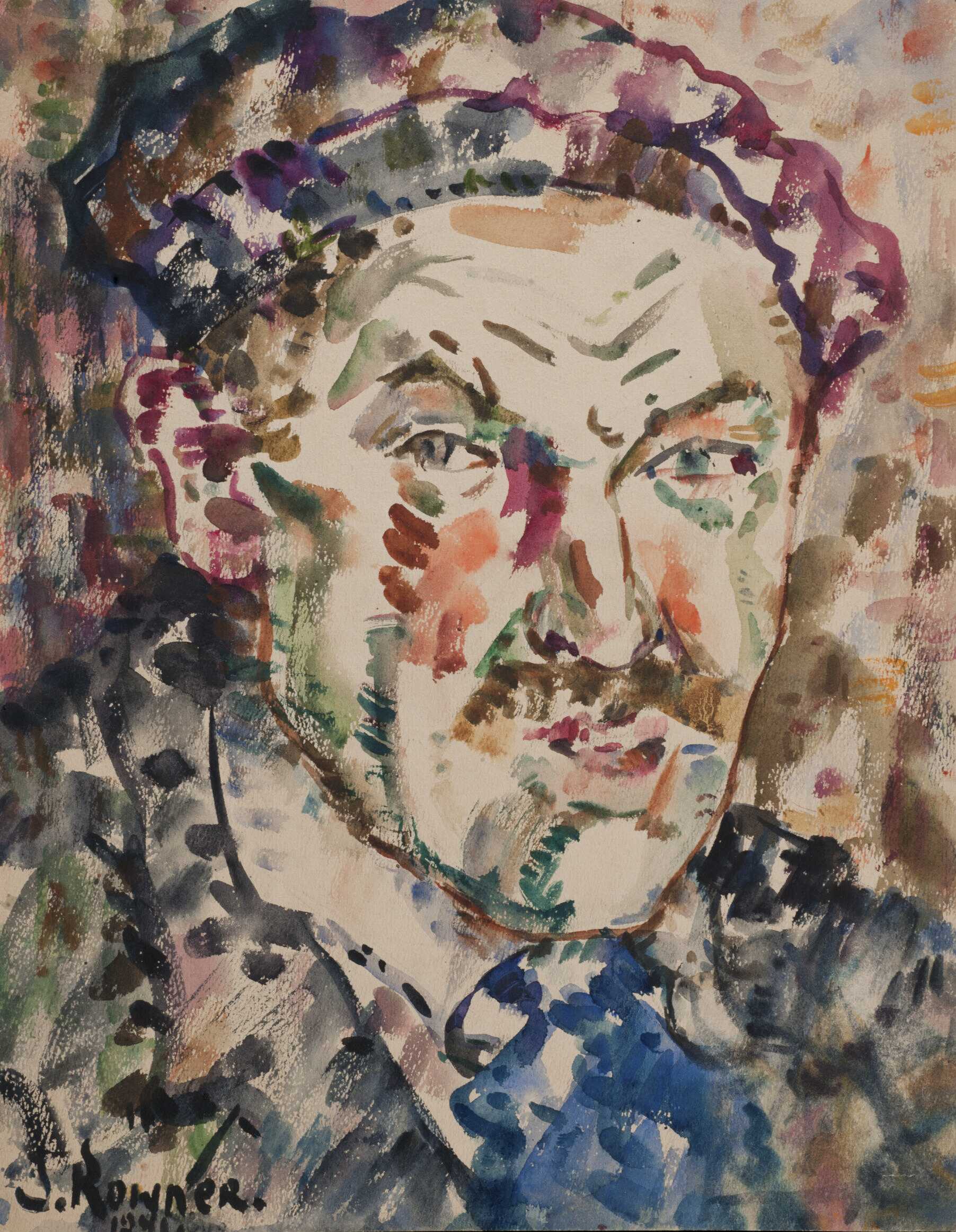

One of the artists employed in the resorty was Józef Kowner (1895–1967), a well-known prewar painter. In the Łódź ghetto he was a “mature artist with a unique style”.[4] Painters, writers, actors and musicians often met in his flat. Kowner’s paintings from this period are characterised by vibrant colours. He captures ghetto scenes – especially street life and work – in stunningly vivid ways. Much of his work survives, and some is in the collection of the Jewish Historical Institute.

Up to a point, the need for commodities and minimum labour costs gave the Germans a reason to keep the Łódź ghetto in existence. But hopes of surviving through work ultimately proved futile in the face of the Nazi plan to exterminate all Jews. The decision to liquidate the Łódź ghetto was made in the spring of 1944, when it was still inhabited by nearly 77,000 Jews. Deportations to Auschwitz-Birkenau began in August 1944. Rumkowski and his family left the ghetto on one of the last transports.

The Łódź ghetto left behind a varied documentation, most of it produced by the Jewish and German administration, but also many personal documents and photographs. A sizeable collection of paintings and decorative art also survived and is presently in the holdings of the Jewish Historical Institute. The kilim is one of them.

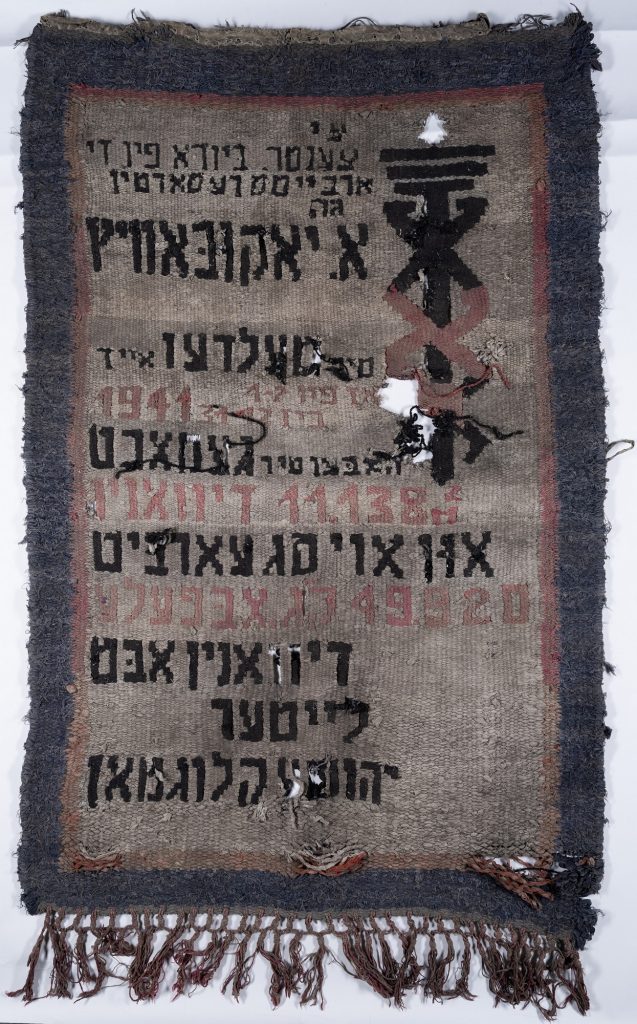

There are two more similar artefacts in the holdings of the Institute. A kilim made in the Carpet Department for Aron Jakubowicz, the head of the Central Bureau of Departments, bears a rose and black inscription in Yiddish on a gray background: “To the Central Bureau of Labour Departments, Mr Aron Jakubowicz. We report that during the period 1.07–31.12.1941 we made 11,138 m2 of carpets and processed 49,920 kg of waste. Head of the Carpet Department Jehoszua Klugman”. There is a blue border with a narrow, rose inner belt and tassels at the bottom.

The other item is a tapestry also made in the same department. The upper end is trimmed with a red canvas belt, while the bottom ends in grey and red tassels. On a grey background in red yarn is the inscription in Yiddish: “Chairman M. Ch. Rumkowski is a symbol of the Jewish spirit and creativity”.

Today’s approach to the “ghetto luck” kilim from the Łódź ghetto differs significantly from how the curators of the 1948 exhibition likely would have seen it. In 1948, the artefact was presented as a symbol of persecution and Jewish suffering under German occupation. Today we also appreciate its artistic value. We also see it as an example of how the ghetto administration tried to support artists, recognising them as important members of the community. At the same time, the subject matter does tell the story of inhuman working conditions. The kilim, however, provides a more nuanced view, supplying insights, deepening our sensitivity, and inviting reflection.

[1] For a broader discussion, see: Agnieszka Haska, “‘To Preserve and Immortalise’: The Activity of the Central Jewish Historical Commission”, in: On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe 1945–1948, Berlin: Deutsches Historisches Museum, 2025, pp. 162–171.

[2] For a broader discussion, see: Samuel D. Kassow, Who will Write our History: Emanuel Ringelblum and the Oyneg Shabes Archive, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007.

[3] Julian Baranowski, Łódzkie getto 1940–1944/The Łódź Ghetto 1940–1944: Vademecum, Łódź: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2009, p. 43.

[4] Jakub Bendkowski, “Józef Kowner. Malarz łódzkiego getta”, in: Uchwycić getto. Codzienność getta łódzkiego oczami artystów, ed. Jakub Bendkowski, Zofia Trębacz, Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny, 2024, p. 151.

Zofia TrębaczDr. Zofia Trębacz is a historian at the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. |