“Shades of Black”[1] – Walter Preisser’s Prints of Violence in Concentration Camps

Tomoko Mamine | 6 November 2025

Plötzensee, Luckau, Wuhlheide, Sachsenhausen, Groß-Rosen, Auschwitz, Buna-Monowitz, Gleiwitz, “Dora”, “Turmalin”, Neustadt in Holstein – these were all stages in the six-year imprisonment of the Jewish artist Walter Preisser, which began with his arrest on 4 December 1938 and ended only with the bombing of the Bay of Lübeck by British fighter planes on 3 May 1945. Twelve prints created by Preisser after his liberation, shown until 23 November 2025 in the exhibition “On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945–1948” at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, bear witness to the violent experiences of those years.[2]

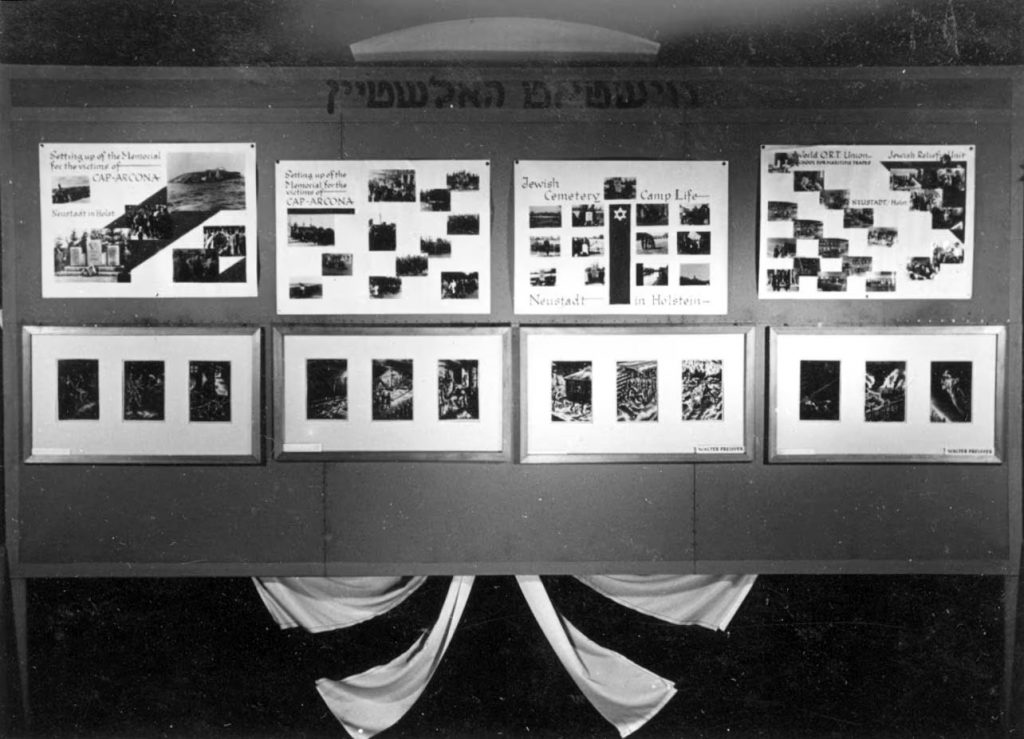

An inconspicuous black-and-white photograph from the exhibition Undzer veg in der frayheyt (Our Path to Freedom), held from July to November 1947 at the Bergen-Belsen DP camp,[3] shows an exhibition panel with the handwritten Yiddish heading “Neustadt Holstein”. Four photo collages are mounted side by side on it, titled “Setting up of the Memorial for the victims of CAP ARCONA”, “Jewish Cemetery, Camp Life”, and “World ORT Union, Jewish Relief Unit”. Below them are four landscape-format wooden frames, each containing three identically sized prints that appear to depict night-time scenes with people. The inscription refers to the name “WALTER PREISSER”.

Born on 15 July 1899 in Posen, Walter Peiser studied at art schools in Munich and Berlin between 1919 and 1921, and from 1923 onwards worked as an artist and commercial designer in Berlin under the pseudonym Walter Preisser.[4] During this period, he created woodcuts, book illustrations, and bookplates for the Maximilian Gesellschaft, the Soncino Society of Friends of the Jewish Book (Gesellschaft der Freunde des jüdischen Buches) and the Otto von Holten publishing house. His work shows the influence of Expressionism, evident in the stark black-and-white contrasts, angular lines, and hatching, but also references to 15th-century woodcut or 17th-century painting – for example in the composition, lighting, and landscape design – or to Japanese woodcut.[5]

Preisser had served as a volunteer on the front lines in France during the First World War and opted for German citizenship in 1922 following the German-Polish Convention on Upper Silesia. In view of the escalating discrimination and persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany, he decided to emigrate and was about to leave when he and his non-Jewish partner were arrested on 4 December 1938. After three months in pre-trial detention in Plötzensee, Preisser was sentenced to imprisonment in Luckau Penitentiary for “Rassenschande” (racial defilement) under Nazi racial policy. Upon his release in June 1940, this was converted into so-called “Schutzhaft” (protective custody), a measure by which the Nazi regime arbitrarily detained people they perceived as a danger, such as political opponents, Jews, homosexuals, or Sinti and Roma. Preisser was first taken to the Wuhlheide labour camp, followed by the concentration camps at Sachsenhausen, Groß-Rosen, Auschwitz, Monowitz-Buna, Gleiwitz, “Dora-Mittelbau” in Nordhausen and “Turmalin” in Blankenburg.[6]

Preisser owed his survival during this period above all to his artistic abilities, which were recognised and made use of by both fellow prisoners and concentration camp personnel. He was commissioned to produce signage, technical and documentary drawings, as well as artistic works.[7] Preisser also used his relatively privileged situation to assist fellow prisoners, such as sixteen- year-old Joseph Sprung, whom he took under his wing in Monowitz as his “camp son”.[8] He ensured that Sprung was trained as a welder by fellow prisoner Norbert Wollheim, who helped organise the Kindertransports in 1938–39 and would later become an important figure in the revival of Jewish life in postwar Germany.

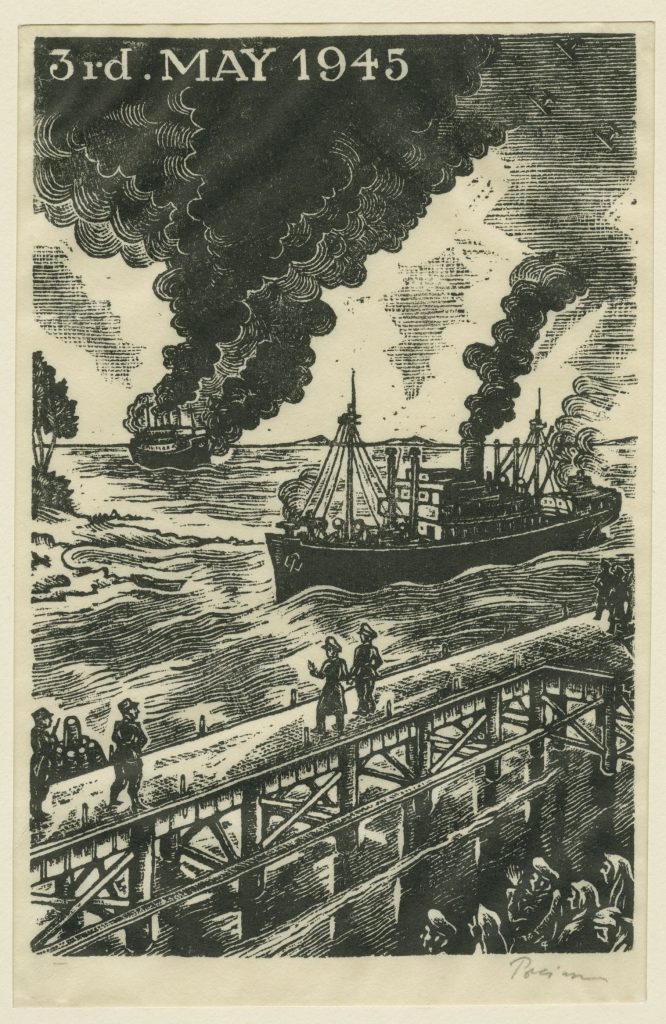

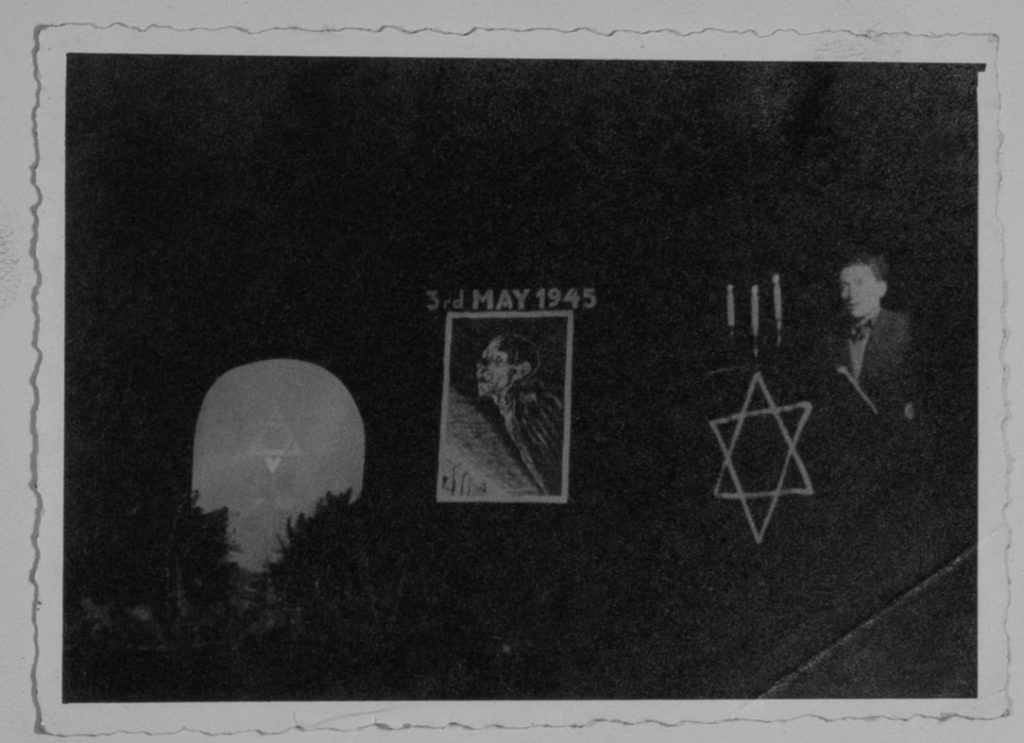

In the spring of 1945, Preisser was taken on death marches and transports to Neustadt in Holstein, where on 3 May 1945 he survivedthe bombing of the Bay of Lübeck by British fighter planes and the sinking of the ships Cap Arcona, Thielbek and Deutschland, which were crowded with concentration camp prisoners. More than 7,000 people were killed in the disaster. Preisser was admitted to the Neustadt DP camp, where he established himself as a portrait painter and was active in the DP community.[9] He created wall paintings for the synagogue and the stage design for a memorial event for the victims of the attack on the Bay of Lübeck, held on 5 January 1947 to mark the inauguration of the Jewish cemetery in Neustadt. He also exhibited graphic works in the aforementioned exhibition at the DP camp Bergen-Belsen.

Preisser became a teacher of commercial art at the vocational school of the worldwide Jewish training organisation ORT (Organisation for Rehabilitation through Training) in Neustadt, which opened in December 1947. In the course of the investigation against Veit Harlan, the director of the antisemitic propaganda film Jud Süß, Preisser was questioned on 30 April 1948 as a witness to the violent excesses against Jewish prisoners in the concentration camps triggered by the film.[10] At the end of 1948, he moved to Hamburg to teach at the newly established ORT school there.[11] Finally, in late October 1949, he followed the repeated invitations of Joseph Sprung, who had emigrated to Australia three years earlier. Preisser and his wife, Marianne Else, boarded the SS Cyrenia in Genoa and arrived in Melbourne on 7 December 1949.[12]

One day before his departure, Preisser dedicated an art portfolio containing twelve woodblock prints to his “comrade Neurath, in memory.” Willi Neurath, a communist from Cologne, had been imprisoned in various detention centres and concentration camps including Neuengamme since 1933 and had survived the bombing of the Cap Arcona. After his liberation, Neurath remained in Neustadt, became head of the state government’s “Department of Political Reparations”, and campaigned for the recovery of the bodies and the commemoration of the victims of 3 May 1945. It is very likely that Preisser and Neurath’s paths crossed in this context.

Walter Preisser, untitled prints from a portfolio of twelve prints, ca. 1947, Mahn- und Gedenkstätte der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf

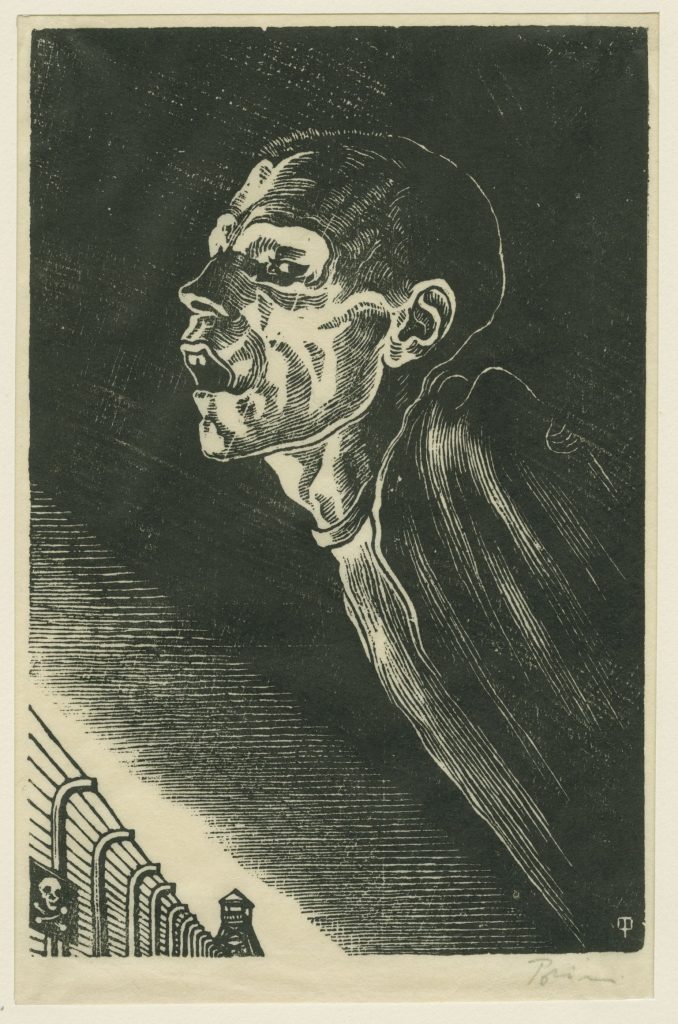

The prints reflect Preisser’s experiences of brutal violence against prisoners in concentration camps, particularly in Groß-Rosen and Monowitz, which he later recorded in writing.[13] The pronounced use of dark areas and recesses, which represent both the darkness of the setting and the incidence of light, creates a sombre, oppressive atmosphere of isolation from the outside world. The faces of the prisoners and the concentration camp personnel are rendered schematically and remain mostly expressionless, conveying an air of indifference and underscoring the everyday nature and ubiquity of these scenes. The distinctly defined contours of the heads and faces, on the other hand, emphasise the bony nature of the shaven heads, hollow cheeks, and emaciated faces of the prisoners, most of whom gaze downwards. The outlines of the bodies and the garments hanging loosely upon them underline their emaciation and the frequently reported swelling of inflamed joints.

Two prints differ from the others in motif and composition. One shows a distant view of a bay with two ships on fire; the inscription “3rd. MAY 1945” makes it clear that these are the burning ships Cap Arcona and Deutschland. The other shows a portrait-like image of an emaciated prisoner who, with his mouth slightly open and his eyes half-closed, seems to float ghostly above a concentration camp fence with a watchtower, oversized against the dark background. Preisser used this motif also for the stage design of the aforementioned commemorative event.[14]

Preisser’s twelve prints thus embody his endeavour to process the violence he experienced on a daily basis, building on his own earlier visual language – first in wood, then in black ink on paper.[15] Unlike the affable portrait drawings he created in the DP camp,[16] these prints represent Preisser’s multilayered artistic reflection on his experiences. Thematically, they refer to the horrors he had recently witnessed, while technically and stylistically they draw on his earlier artistic approach, which had come to a standstill during his imprisonment. In this way, the prints bridge the gap between the violence and destruction, remembrance and commemoration, and the restoration of hope for a better future – the overarching theme of both the exhibition panel on Neustadt and the exhibition Undzer veg in der frayheyt as a whole. That Preisser, who became an Australian citizen on 12 November 1964,[17] lived and worked as a commercial artist in a small house in Melbourne’s Richmond district until his death on 16 October 1980,[18] underlines this continuity.

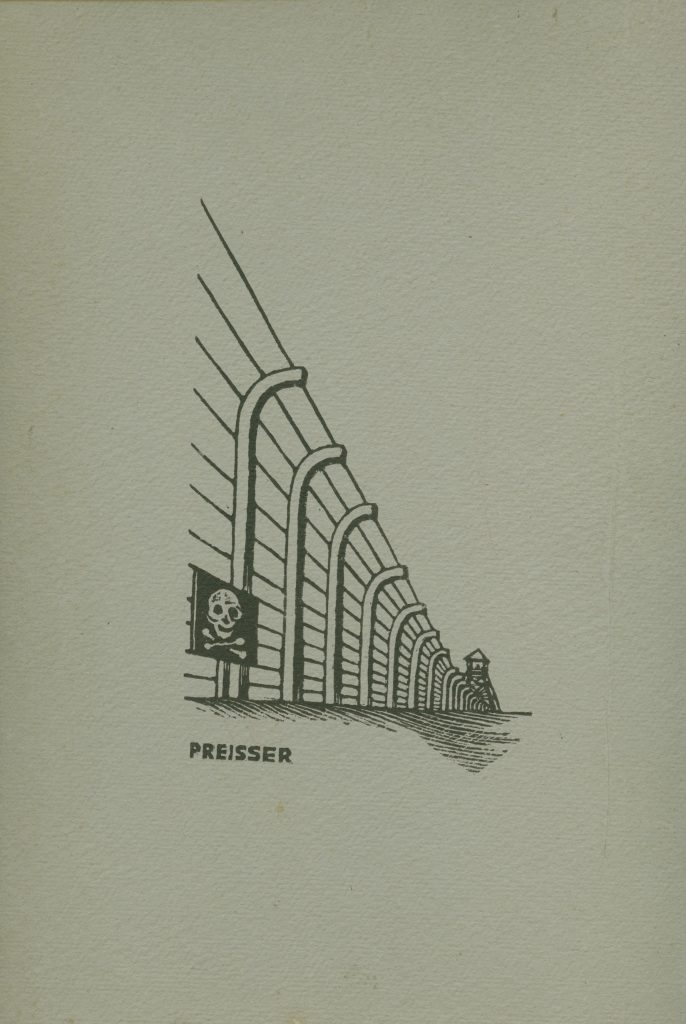

The cover of the portfolio containing Preisser’s twelve prints features a view of the concentration camp fence, seemingly stretching into the distance – the same motif included in the print described above. The fact that Preisser, in his new home country, designed wire-mesh fences for sheep farming – and that the last photo in his album “Neustadt-Holstein, 1945–1948” shows him relaxing amid a display area of the Australian Reinforcing Company – seems an irony of fate.

[1] Walter Preisser, Shades of Black: An Artist Survives, edited typescript, Melbourne Holocaust Museum.

[2] The author would like to thank Anna Hirsh, Bruno Neuwirth-Wilson, the colleagues of the team of the exhibition Gewalt ausstellen at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf, of the Melbourne Holocaust Museum, and of the KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme for their valuable advice and generous support.

[3] Agata Pietrasik, “Exhibiting the Holocaust at the Majdanek Concentration Camp and the Bergen-Belsen DP Camp”, The Journal of Holocaust Research, vol. 37, no. 3, 2023, pp. 271–296.

[4] Luckau prison personnel file on Walter Peiser, Arolsen Archives, 10010193, DocID 12123510. The name W. Peiser can also be found in the admission list of the teaching institution of the Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Decorative Arts) in Berlin for the winter semester 1921/22, UdK Archive 7–255.

[5] Prints and book illustrations by Preisser have been preserved, including those made for: Hans Christian Andersen, Die Nachtigall, Berlin 1923; Theodor Wolff, Anatole France, Berlin 1924; Das lasterhafte Leben des weiland weltbekannten Erzzauberers Christoph Wagner gewesenen Famuli und Nachfolgers in der Zauberkunst des Doktor Faust, Berlin 1925; Stefan Zweig, Rahel rechtet mit Gott: Legende, Berlin 1930; Neun Holzschnitte: Die grosse Stadt, Berlin 1930.

[6] Personnel file of the Luckau Penitentiary on Walter Peiser, Arolsen Archives, 10010193, DocID 12123510.

[7] Jayne Josem, “Walter Preisser: The Art of Survival – Curator’s Corner”, Melbourne Holocaust Museum, 28 May 2015, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9mFG5KwgVg (last accessed: 20 September 2025)

[8] Preisser, Shades of Black;Stefan Keller, Die Rückkehr. Joseph Springs Geschichte, Zurich 2003. In 1998, Sprung, who had changed his surname to Spring after emigrating to Australia, sued Switzerland for complicity in the Holocaust.

[9] “O.R.T. Zonal Vocational School Neustadt Holstein”, c. 1948, ORT Archive, https://ortarchive.ort.org/fileadmin/d/germany/d18a019.pdf (last accessed: 20 September 2025)

[10] Interrogation transcript, 30 April 1948, Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial Archive.

[11] Preisser, Shades of Black, p. 230. For information on the ORT School in Hamburg, see: World ORT Union: The Bi- Weekly Summary, vol. II, no. 34, 15 November 1948, p. 3. Preisser can be seen with his class in a newsreel about the ORT school in Hamburg: Welt im Film, no. 191/1949, February 1949, https://digitaler- lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/30823/689878 (last accessed: 20 September 2025).

[12] Passenger list of the SS Cyrenia upon arrival in Fremantle on 1 December 1949, National Archives of Australia,K269, Item ID 9243283.

[13] Preisser, Shades of Black.

[14] Unzer Sztyme, no. 17, 25 January 1947, pp. 26–27, quoted from: Sigrun Jochims, “‘Lübeck ist nur eine kurze Station auf dem jüdischen Wanderweg’. Die Situation der Juden in Schleswig-Holstein 1945–1950 im Spiegel der Zeitungen Undzer Schtime, Wochenblatt und Jüdisches Gemeindeblatt”, https://www.akens.org/akens/texte/info/33/333413.html (last accessed: 20 September 2025)

[15] The Melbourne Holocaust Museum collection holds a print dated 9 November 1948, which seems to be related to the twelve prints discussed here and shows a burning synagogue beneath the date “9th NOVEMBER 1938”, i.e. the November Pogrom, which marked a decisive moment in the escalation of violence against Jews.

[16] Some of Preisser’s drawings from his time in the DP camp are documented in his album “Neustadt-Holstein, 1945– 1948” in the collection of the Melbourne Holocaust Museum. Examples can be seen in: Jayne Josem, “Walter Preisser: The Art of Survival – Curator’s Corner”.

[17] Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, no. 37, 6 May 1965, p. 1680.

[18] Will, Grant of probate, 881/859 Walter Peiser, Public Record Office Victoria. Preisser advertised e.g. in: The Australian Jewish Herald, 12 July 1957, p. 6.

|

Tomoko MamineTomoko Mamine is project assistant for the exhibition “On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948” at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |