A Beluga in the Rhine? How a stray white whale made German environmental history in 1966

Martin Baumert | 17 December 2025

In the temporary exhibition “Nature and German History. Faith – Biology – Power”, a film can be seen that features a beluga whale known as “Moby Dick in the Rhine” that made history in 1966. Martin Baumert, research associate of the exhibition, explains how the whale fared in the Rhine and what importance the beluga achieved in the environmental discussions of the 1960s.

On 18 May 1966 at around 9.30 am, the tanker “Melani” called the Duisburg river police and reported, “We have sighted a white whale at Rhine kilometre 778.5.”[1] The police suspected that alcohol was involved, given the implausibility of the report – belugas normally live in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters.[2] The captain’s breathalyser test was negative, and the police saw the whale with their own eyes. The director of Duisburg Zoo, Wolfgang Gewalt (1928–2007), who had been called to the scene, was impressed: “Man, that’s a whopper,” he exclaimed, and called it “a zoological sensation”.[3]

Public interest in the whale grew in the following weeks. The name “Moby Dick”, from Herman Melville’s famous novel, quickly became established.[4] From The Times to the New York Herald Tribune and Pravda, the international press reported on the stray white whale.[5] The beluga swam up the Rhine as far as Bad Honnef, south of Bonn, more than 350 kilometres from the mouth of the river. The whale in the Rhine dominated the news headlines for several weeks and attracted countless visitors to the Rhine restaurants. The duo Christopher & Michael even dedicated a song to it entitled “Im Rhein da schwimmt ein weißer Wal” (A white whale is swimming in the Rhine).[6]

On 13 June 1966, it even interrupted a federal press conference: Defence Minister Kai-Uwe von Hassel was about to report on the tense situation in NATO following France’s withdrawal from the defence alliance when the head of the Federal Government’s Press and Information Office, Karl-Günther von Hase, interrupted him with the words: “I have just received news from a special courier that Moby Dick is in front of the Federal Parliament.”[7] The assembled capital-city press corps then rushed to the Rhine, preferring the animal sensation to everyday political business.

Of course, “Moby Dick in the Rhine” also had a completely different story to tell, namely that of the pollution of Germany’s waterways. Within a few days, the whale had developed a skin rash, and zoo director Gewalt explained in an interview, “[under these circumstances] he will die.”[8] But what was the problem now? Why was the whale no longer in danger of not surviving in the Rhine? To answer these questions, we need to take a brief look at the environmental history of the Federal Republic of Germany.

“Phenol-smelling waterways”[9]

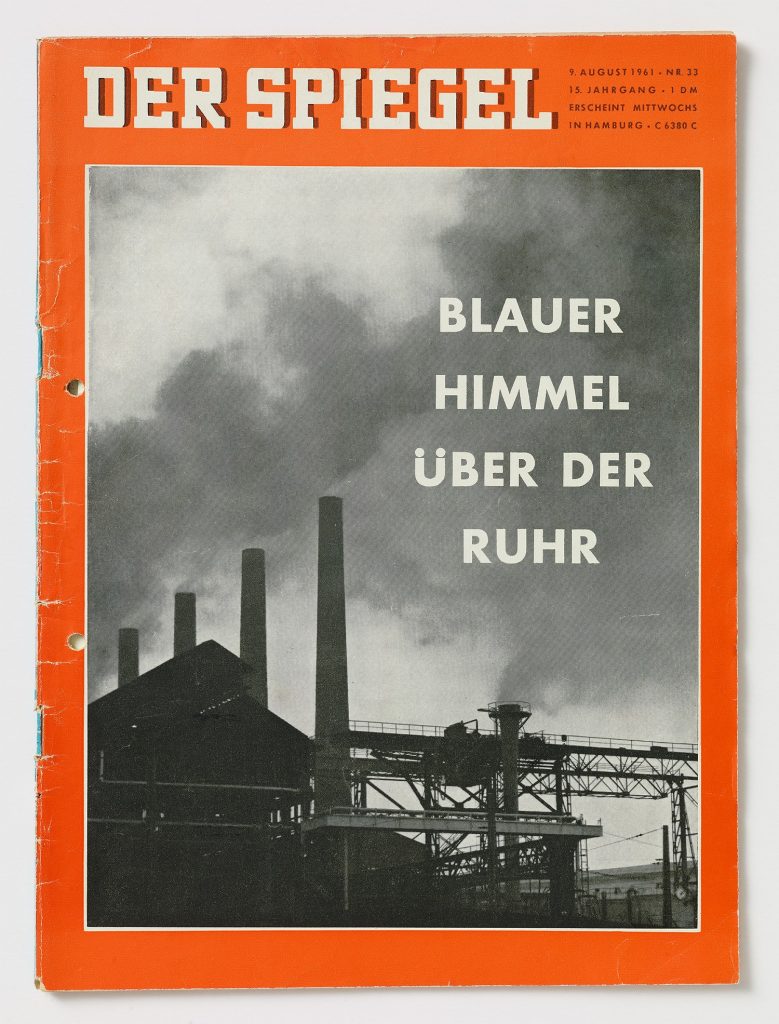

Residents living on the banks of the Rhine have always used the river to dispose of their waste. For a long time, this did not cause serious problems, as the number of people was limited, the amount of waste was small, and the composition of the waste usually caused only local environmental damage.[10] For a long time, the river was still able to absorb the pollutants itself. This changed increasingly in the course of industrialisation and escalated into an ecological disaster in the 1950s. The transition to the age of mass consumption is referred to as the “Great Acceleration”[11] or “1950s syndrome”[12]. For West Germany, the “economic miracle” marked this radical change in society’s relationship with nature.[13] Increasing consumption turned what had previously been a rather localised problem of environmental pollution into an almost ubiquitous one. From the Swiss border northwards, the Rhine increasingly turned into a sewer. In 1985, 11 million tons of chloride, 4.6 million tons of sulphate, 828,000 tons of nitrate, 90,000 tons of iron, 38,200 tons of ammonium, 28,400 tons of phosphorus, 4,350 tons of zinc, 2,500 tons of chlorine compounds, 681 tons of copper, 665 tons of lead, 578 tons of chromium, 530 tons of nickel, 126 tons of arsenic, 13 tons of cadmium, and 6 tons of mercury flowed from Germany into the Netherlands.[14] The wastewater from the Ruhr District had a particularly damaging effect. Not only did coking plants, power stations and steelworks pollute the air, they also turned the little river Emscher into a stinking cesspool, the “sewage canal of the Ruhr District.”[15] The strong-smelling phenols from coal and petroleum processing in particular turned the Rhine into a “brown broth”[16]. In 1961, Willy Brandt, the Social Democratic chancellor candidate, not only demanded that “the sky over the Ruhr must become blue again”, but also pointed to the causes of “air and water pollution.”[17] Added to this was the chemical industry, which operated numerous sites between Ludwigshafen (BASF) on the Upper Rhine, past Bieberich (Chemische Fabrik Kalle & Co.) and Leverkusen (Bayer), and on to Uerdingen (Bayer) on the Lower Rhine. But the population also contributed to the pollution, as sewage was often thrown into the river untreated. At that time, the Rhine was largely biologically dead.

Today, the situation on the Rhine has improved considerably thanks to the ban on discharging untreated sewage. The river has become an example of the positive effects that legal regulations can have on environmental protection. The water quality is predominantly Class II, “moderately polluted”.[18] The concentration of pollutants has also improved noticeably. For example, mercury pollution has fallen by 70 per cent since 1985.

“Even Gewalt can’t fix it”[19]

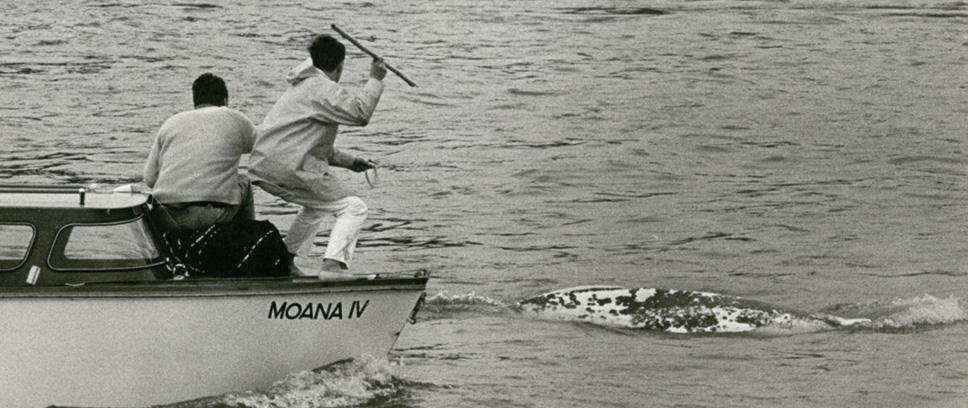

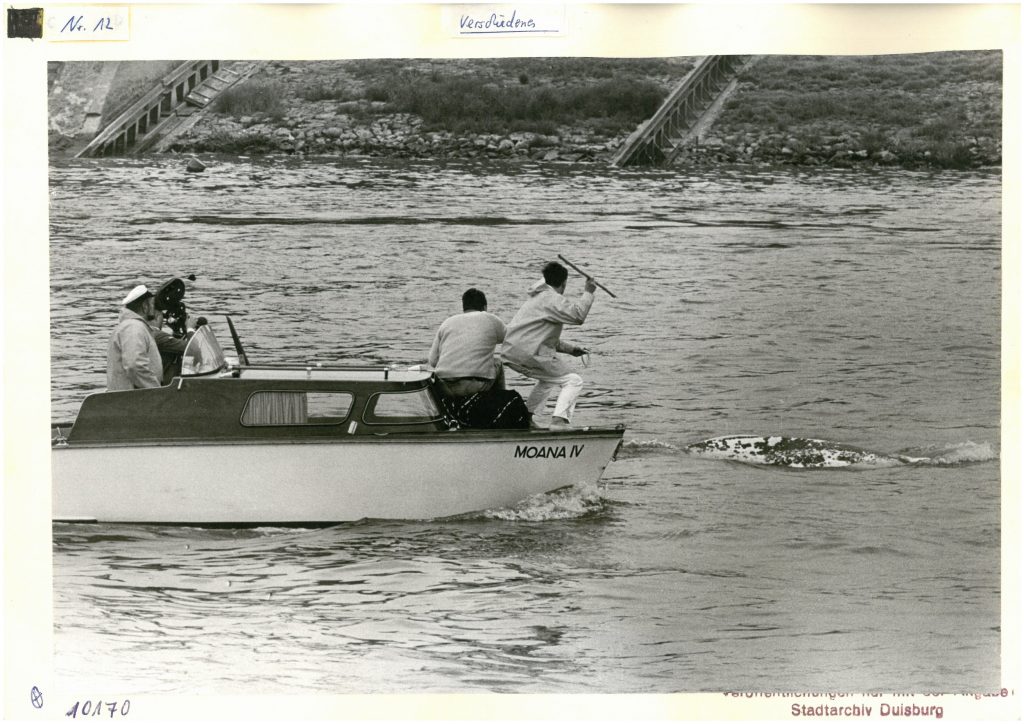

Back to the beluga in 1966: Since the whale was threatened by the environment, zoo director Wolfgang Gewalt tried to catch it and transfer it to the Duisburg Zoo’s dolphinarium. As the media saw it, he played the role of Captain Ahab from Melville’s novel. Initially attempting to corner the beluga with knotted tennis nets, he later tried to capture it with tranquiliser darts[20], a risky undertaking, to say the least. Whales are mammals that need to come to the surface to breathe. A stunned whale could easily drown. Ultimately, all attempts failed and the zoo director called off the hunt for “Moby Dick” on 10 June 1966. This was not only because it had failed, but also because the public objected to his hunting methods. While concerned citizens saw the methods a violation of animal welfare laws and filed criminal charges, activists chartered an airship to throw oranges at the zoo director to keep him from catching the whale.[21] The Bild newspaper even demanded: “Arrest Dr. Gewalt!”[22]

Contrary to Dr. Gewalt’s predictions, “Moby Dick” survived the conditions in the Rhine. After his excursion to the Federal Press Conference, he followed the course of the river towards its mouth and on 16 June 1966, “at 6.42 pm, the white beluga whale reached the open sea at Hoek van Holland.”[23] Although this marked the end of the media interest, the beluga’s visit almost 60 years ago is still remembered in the region: an excursion steamer, shaped like a whale, still bears the name “MS Moby Dick” in memory of the event.[24]

Two questions remain: Where did the whale come from and where did it go? Both routes are much more difficult to reconstruct than “Moby Dick’s” journey down the Rhine. Belugas do swim in river estuaries, but the North Sea is not part of their natural habitat. It is possible that it came from a distressed transport ship off the coast of Great Britain in the summer of 1965 with four belugas on board, three of which are known to have escaped.[25] Even more mysterious is its whereabouts after its Rhine journey. Just a few days after it was last seen in the Netherlands, the media reported a stranded white whale in Sweden. However, there is no firm evidence that the animal sighted was the one from the Rhine.[26]

The appearance of the beluga in 1966 did not mark a turning point in the history of environmental policy in the Federal Republic of Germany. Nevertheless, it was an important event in German environmental history. People’s empathy with the endangered animal drew public attention to the dire situation of Germany’s waterways.

[1] Simon Michaelis: Das weiße Wunder vom Rhein, in: Spiegel online, 18 May 2016, under: https://www.spiegel.de/geschichte/beluga-wal-von-1966-moby-dick-vom-rhein-a-1092621.html, accessed: 04.12.2025.

[2] Wolfgang Gewalt: Der Weißwal, Wittenberg 1976, p. 69 ff.

[3] Michaelis 2016.

[4] Dietmar Bartz: „Moby Dick“ und der giftige Rhein, in: taz, die tageszeitung, issue 6534 from 28 August 2001, p. 14.

[5] Wolfgang Gewalt: Auf den Spurend er Wale. Expeditionen von Alaska bis Kap Hoorn, Bergisch Gladbach 1988, p. 13.

[6] Ibid., p. 19.

[7] Ulli Kulke: Walfang im Rhein raubte Deutschland den Verstand, in: WELT, 05. Mai 2016, under: https://www.welt.de/geschichte/article155048267/Jagd-nach-Moby-Dick-Walfang-im-Rhein-raubte-Deutschland-den-Verstand.html, accessed: 08.12.2025.

[8] WDR mediagroup GmbH (Hg.): Hier und Heute. Dr. Gewalt stellt die Waljagd im Rhein ein, 10 June 1966, 00:02:22–00:02:26.

[9] Gewalt 1988, p. 14.

[10] Thomas Rommelspacher: Das natürliche Recht auf Wasserverschmutzung. Geschichte des Wassers im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, in: Franz-Josef Brüggemeier/Thomas Rommelspacher: Besiegte Natur. Geschichte der Umwelt im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, München ²1989, pp. 42-63, here pp. 46-50.

[11] John Robert McNeill/ Peter Engelke: The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene since 1945, Cambridge 2016.

[12] Christian Pfister: Das „1950er Syndrom“ – Die umweltgeschichtliche Epochenschwelle, in: Christian Pfister (ed.): Das 1950er Syndrom. Der Weg in die Konsumgesellschaft, Bern Stuttgart Wien 1995, pp. 51–95, here pp. 54–60.

[13] Vgl. Ernst Langthaler: Unterbrochene Beschleunigung. Österreichs Wirtschaft im Nationalsozialismus aus sozioökologischer Perspektive, in: zeitgeschichte 50 (2023), Heft 2, pp. 167 – 192, here p. 168.

[14] Rommelspacher 1989, p. 42.

[15] Detlef Stoller: Halbzeit am Abwasserkanal des Ruhrgebietes, in: taz, die tageszeitung, Ausgabe 4775 from 16 November 1995, p. 12.

[16] Gewalt 1988, p. 15.

[17] Kai Doering: Blauer Himmel über der Ruhr. Wie Brandt den Umweltschutz begründete, in: vorwärts, 28. April 2021, under: https://www.vorwaerts.de/geschichte/blauer-himmel-uber-der-ruhr-wie-brandt-den-umweltschutz-begrundete, accessed: 10.12.2025.

[18] Reblu GmbH: Die Wasserqualität des Rhein, under: https://www.test-wasser.de/wasserqualitaet-rhein, accessed: 09.12.2025.

[19] Gewalt 1988, p. 20.

[20] Gewalt 1988, p. 16 and 20 f.

[21] Johanna Kemper: „Moby Dick“ im Rhein gesichtet, in: Bayern 2. Kalenderblatt vom 18. Mai 2018, under: https://www.br.de/radio/bayern2/sendungen/kalenderblatt/moby-dick-im-rhein-gesichtet-102.html, accessed: 09.12.2025.

[22] Gewalt 1988, p. 14.

[23] Gewalt 1988, p. 26.

[24] Stefan Knopp: MS Moby Dick wird 40, 03. Oktober 2016, under: https://ga.de/bonn/ms-moby-dick-wird-40_aid-43047915, accessed: 10.12.2025.

[25] Cf. Gewalt 1988, p. 27.

[26] Ibid., p. 26 f.

|

|

Martin BaumertDr. Martin Baumert is a research assistant for the exhibition “Nature and German History” at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |