Collecting and researching: A closer look at the Augsburg Pictures of the Months

Dr. Sabine Beneke | 4 June 2025

The blog series on the collection work of the Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM) deals with core questions such as the decision for or against the acquisition of certain objects, the different ways in which they are found and acquired, the changing research questions posed by the objects in the collections, the provenance and origin of the objects, and many other aspects.

An important part of collection work is the research of an object, which can be carried out, for example, based on new research of the object’s context, in the course of a restoration, or within the framework of a new exhibition project. Dr. Sabine Beneke, head of the art collection of the Deutsches Historisches Museum, undertook a detailed picture analysis of the painting cycle known as the “Augsburg Pictures (or Labours) of the Months” within the context of a recent restoration. She discovered new motifs and composition lines, which has led to a new overall interpretation of the painting cycle.

The older a museum object is, the more likely it is that the exact time and purpose of its origin and the place for which it was made will not be known. Sometimes everything about its history has been cleared up, at other times only part of it, and in the worst case nothing at all. When the Deutsches Historisches Museum acquired the four-part series of large-scale paintings from the 16th century in 1990, it was only known that the cycle represented the twelve months, whereby each painting comprised one quarter of the year and the respective three months were named. The reference to Augsburg was revealed in the architecture of the city in one of the pictures. Based on the people, clothing and actions shown, the reference to the leading social class was clear: the patricians – the urban nobility – presented themselves at table, in knightly games, on the hunt, and as councillors of the city of Augsburg. It was not yet known who originally commissioned the paintings.

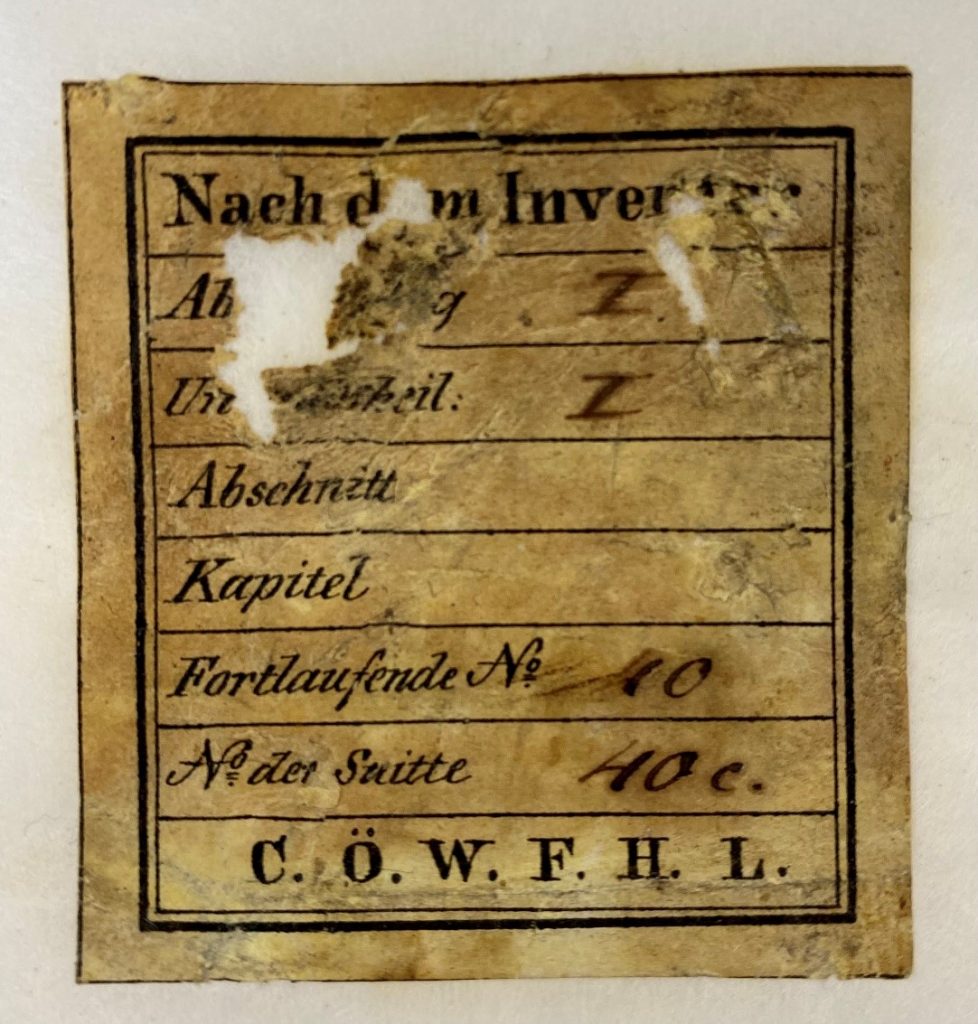

A recent restoration provided the opportunity to take a careful look at the pictures to learn more about them. Our attention was drawn to an inventory sticker on the back of the old picture frame, on which the canvas had been mounted.

The top line reads: Nach dem Inventar (from the inventory). The letters at the bottom: C.Ö.W.F.H.L. can be interpreted as: CÖW = Caroline von Öttingen-Wallerstein, FHL = Fürstliche(s) Haus(verwaltung) Leutstetten (princely property management Leutstetten). This gives a clue to the former owners. Caroline was the daughter of Ludwig, Prince of Öttingen-Wallerstein (1791–1870), who acquired Schloss Leutstetten at Lake Starnberg in 1833. But who owned the paintings before that? They were not part of the old castle inventory, and the Oettingen-Wallerstein family did not belong to the Augsburg patrician families, but rather to the nobility in the Holy Roman Empire.

It is certain that the paintings had not been on permanent display from the beginning, but rather – as was determined during the restoration – that at a certain time they had been treated incompetently and coarsely. There are many different kinds of flaws. They could be explained in part by the fact that the canvases had been removed or cut out of a representative framing wall panelling or from their wooden architectural frames. In the 16th century, it would have been suitable to present such a large-scale painting series in this way.

A history museum collects artworks according to different criteria than an art museum. The quality that a historical museum looks for is not necessarily found in the search for “masterworks” by famous artists and sculptors. Historical knowledge – history that can tell a story – can also be found in works by unknown artists. Nonetheless, the methods of art history remain a prerequisite for the historical understanding of the works. The objects are not to be understood as mere illustrations of history, but as historical sources. Art history teaches us how to interpret them: Does a new art-historical view of the pictures provide a new way of reading them? The Deutsches Historisches Museum began a thorough study of the paintings immediately after acquiring them, which involved searching for important models whose motifs could provide information about the workshop that created the cycle. The history of Augsburg and its patricians in the 16th century also provided a historical framework for the search. But many questions remained unanswered.

Art historians know that an artwork series like the Augsburg Pictures of the Months always tells a story. They resemble a novel that is put together out of individual chapters. This was the approach to a renewed examination of the works as a “cold case”: Would a closer look at the four pictures, based on new research, find indications that would give us greater insight into the intent and purpose of the pictures – centuries after their creation and decades after the first extensive examination? Could more be discovered about their origin?

An analysis of the compositions, their strategies and their rhetoric, as well as the emphasis given to the motifs through artistic means, led to even more still unanswered questions. Which motifs were based on previous models used by the artists, and which ones were new and therefore possibly of special significance? A fundamentally important question was the opening of the narrative – where did it start? It should definitely be found in Picture 1 with the months of January to March. Did the story begin with the perspectivist middle of the composition or with the classic reading direction from left to right? The identification of two people in the room on the left could be seen as the beginning of a narrative about the Fugger family, because Jakob Fugger the Rich (1459–1525) sits at the table, recognisable through his famous golden cap. To his left, Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519) conducts the conversation, identifiable by his typical attire, including the hat, which is shown in contemporary portraits of him.

The enigmatic questions about motifs that are of great importance for the narrative due to their position in the picture or painterly accentuation could only be solved gradually. With Picture 4 (October-December), which offers a look at the city of Augsburg around 1530, it took a long time to “decipher” the meaning of the horseman in the centre of the painting.

He is shown to be different from the councillors in the foreground who are just leaving the city hall and from other people depicted in the picture through his clothing and prominent moustache. He has a sword on his left side and carries a staff in his right hand. He must be a stranger.

By showing Emperor Maximilian in the opening scene in Picture 1, the Fugger history is closely connected with the House of Habsburg, which provided the emperors of the Holy Roman Empire for centuries. Was this the key to understanding Picture 4 and the central figure of the horseman? The depiction of a captain could be identified as serving as a model for the particular clothing. He arrived in the entourage of Emperor Charles V to attend the Imperial Diet in Augsburg in 1530. This provided an exact historical location of the scene. Not only the history of the Fuggers was closely connected with the emperors, but also that of the imperial city of Augsburg.

The research of the four paintings can be described as a puzzle: the pictures come together as a narrative piece by piece. The deciphered motifs led to new questions, new research, and new solutions. Bit by bit the evidence came together to form a complete picture: the four paintings show a dynastic story of the Fugger family, created at the beginning of the 1580s and commissioned by Hans Fugger (1531–1598), a great-nephew of Jakob Fugger the Rich. Today it gives us insight into the social, economic and political history of the Holy Roman Empire in the 16th century.

The publication Die Fugger-Saga. Zur Provenienz und Auftraggeberschaft der „Augsburger Monatsbilder“ provides an overview of the research of all four pictures.

Dr. Sabine BenekeDr. Sabine Beneke is the head of the collection “Arts: Paintings – Sculptures” at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |