Surviving Spring:

The Long Final Days of WWII in Europe

Thomas Jander | 6 May 2020

1945 was the last year of the Second World War. When the year began, anything less than an Allied victory was now inconceivable – Allied superiority was by this point too great, and the German military, what remained of it, lay in tatters. And yet the war would, indeed, drag on and it ultimately took another four and a half months before the final shots were fired. Over those few months, the war would claim countless more victims. Thomas Jander, Head of Documents at the DHM and the man behind the curatorial intervention ‘Deported to Auschwitz’, writes about the long drawn-out process that led to the ceasefire in Europe by taking a special look at the personal history of one Holocaust survivor, Sheindi Miller-Ehrenwald.

World War II officially ended – on European soil at least – on 9 May 1945, when, shortly after midnight in the Berlin district of Karlshorst, Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW – Armed Forces High Command), sat at a table with representatives of the Luftwaffe and the German navy at his side, and signed the declaration of unconditional surrender of all German armed forces while the Soviet Supreme Commander, Georgi Konstantinovich Zhukov, observed events from further up the table. Although the Wehrmacht troops had already formally capitulated to General Eisenhower in Reims, France, some 22 hours earlier, Joseph Stalin insisted that the act be repeated in the German capital under Soviet command – a sign of his mistrust of the western Allies and his desire to underscore both his own role and the symbolic power of holding such a ceremony in Berlin (which had, after all, fallen to Soviet, not American troops).

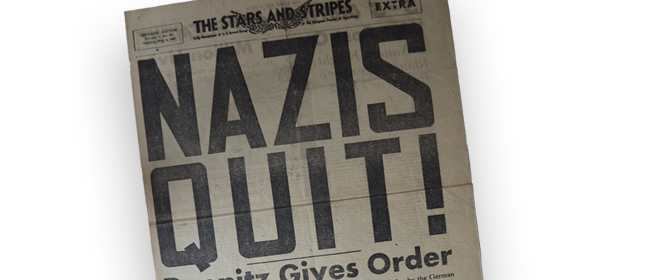

Special edition of Stars and Stripes, the US armed forces magazine, on the Allies’ victory over the German Reich, issue date: 7 May 1945 © DHM

Chief of the OKW, Wilhelm Keitel, General Stumpff, and Admiral von Friedeburg at the signing of the declaration of surrender in Berlin-Karlshorst on 8/9 May 1945 © DHM

Fighting

After a total of 2077 days of war, the guns now fell silent in Europe. But for many people, particularly in western and southern regions, the war had already ended. The long end of the Second World War took many weeks and was experienced in very different ways. For contemporaries of all persuasions, the spring of 1945 would be remembered for its strange blend of hope and fear: some Germans still held hopes for the ‘final victory’ (Endsieg) and now faced fears that the victors would wreak terrible revenge, while others nurtured long-held hopes for the final surrender and ruination of the Nazis’ ‘Third Reich’ and feared that, although so close, they may not live to see it. The entire focus of the European war now shifted to Germany itself, with each town and village fought for, one by one. The threat of death and destruction no longer came merely from the air, but everywhere where German ground troops continued the hopeless and senseless fight against the Allied forces. In this final chapter of the conflict, war was also now waged against those civilians who showed a willingness to hand over their farm, village, or town to the Allies without putting up a fight. On Hitler’s orders, the battle on German soil was to be fought by the Wehrmacht units with dogged savageness – and it was.

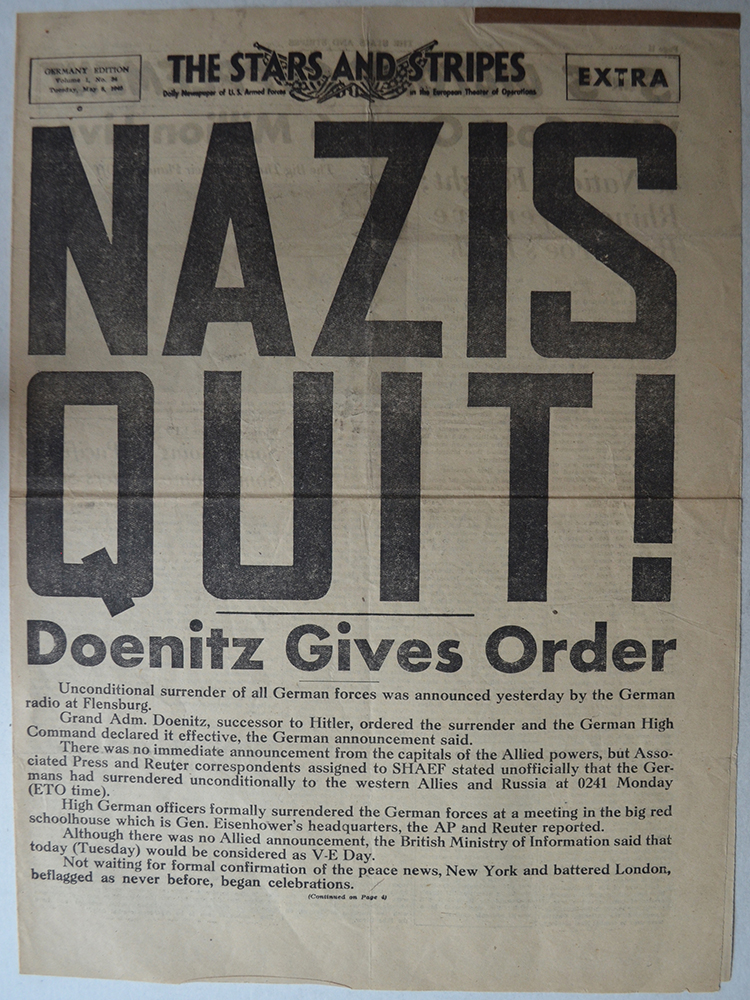

Edition of the Berlin daily Das 12 Uhr Blatt of 24 April 1945, featuring anti-Soviet rallying calls for the civilian population © DHM

In the last weeks of the war, there may have been no more coherent eastern or western front to speak of, but even in the ‘atomized’ war, with isolated pockets of conflict, there were still enough soldiers prepared to hold out for as long as possible, even in small groups, despite the growing shortage of weapons, munition, and fuel. Those born in 1926 or later were known as the Flakhelfer Generation because they had grown up with the Hitler Youth and, as ‘flak helpers’, had assisted in anti-aircraft artillery defence as mere children. Due to their complete indoctrination under the National Socialists, they were routinely abused as the last particularly zealous – even fanatical – soldiers available for sacrifice in defensive battles and ‘last stands’. Indeed, one fitting sight in these last days of wartime was of 16 or 17-year-old boys (of which there were 650,000 in the Wehrmacht in 1945), with rolled-up sleeves in uniforms that didn’t fit them, fighting, not just for their country, but the only regime they had ever known.

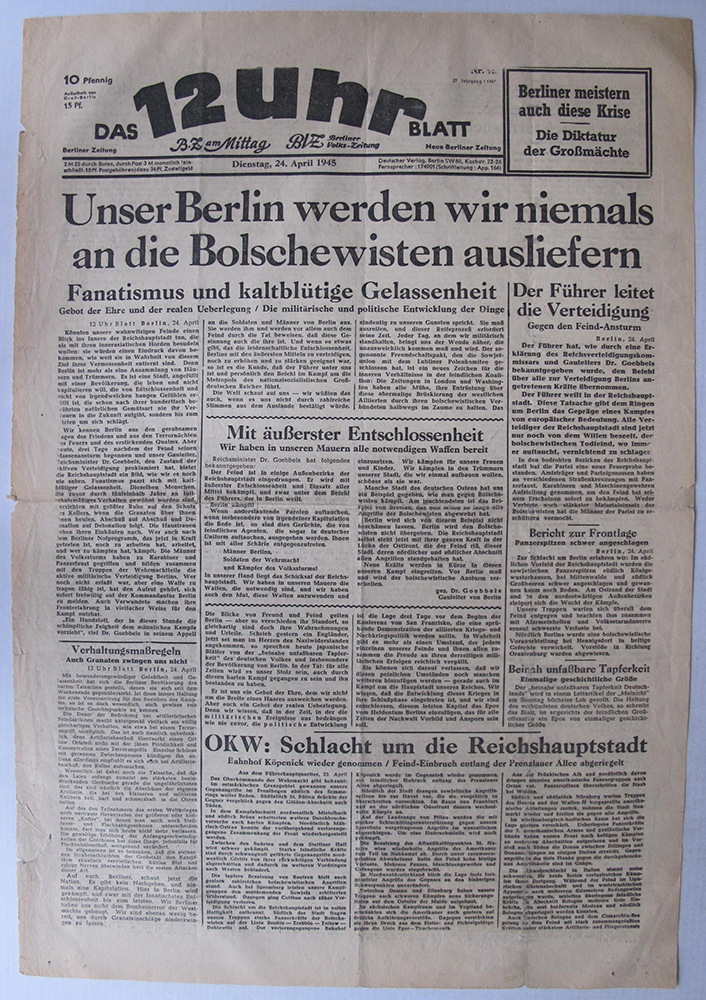

Transportation certificate for a wounded 16-year-old soldier, including note from medical officer for the amputation of his upper right arm, dated 7 April 1945 © DHM

Soldier of the Red Army leads captured Wehrmacht child soldiers through Berlin-Reinickendorf in May 1945 to be transported to a camp as prisoners of war © DHM

Dying

In contrast to the previous years of conflict, in 1945 the OKW stopped collating data on the precise numbers of fallen Wehrmacht soldiers. For this reason, historians now assume on the basis of retrospective calculations that over 1.1 million soldiers died in the months January to May 1945. In other words, the last 130 days of the Second World War in Europe accounted for a third of all German soldiers killed in action. For the Allies, the determined, desperate resistance meant they too incurred heavy losses. Especially in the Red Army, hundreds of thousands of soldiers fell in just the last year of conflict.

At the same time, in the last months of the war, the Allies intensified their air raids and it was notably not until 1945 that many German cities suffered the most devastating bombing raids of the entire war. Almost half a million tons of incendiaries were dropped on German territory in 1945. To put that in perspective: in a mere four and a half months, more bombs were dropped over Germany than in the whole of 1943 put together. No exact figure has ever been determined for the number of people who lost their lives in the carpet bombing. Estimates agree on a figure of 115,000, primarily civilian, deaths. In the end, one fifth of all homes in the German Reich were destroyed.

A young couple in front of their apartment in western Germany, destroyed in April 1945 © DHM

The greatest fear among Germans – soldiers and civilians alike – was of the approaching Red Army. And indeed, after three and a half years waged in a war of attrition (or rather ‘war of annihilation’ – Vernichtungskrieg) against the Soviet Union and specifically its Slavic people, the fear of revenge could hardly be called unfounded. However, the violence of the Soviet soldiers, which mainly targeted German women, was more a reflection of troop barbarity rather than a politically motivated act. Thus, as soon as the Soviet troops were known to be approaching, the civilian population fled en masse westwards. By early March 1945, almost 8.5 million people had fled from the eastern German regions. Nearly 1.5 million more internally displaced people came from the western cities that had since fallen to the Americans and British. And on top of that, there were almost 5 million elderly, women, and children who had escaped the aerial bombardment of their cities by fleeing to the surrounding countryside.

While the thunder of Soviet artillery and drone of overhead Allied bomber units filled most Germans with terror, for others the same sounds were signals of hope. Above all, those imprisoned in concentration camps and other Nazi camps for forced labourers or political prisoners longed for liberation and ultimately saw such Allied raids as a chance of survival.

In order to exploit prisoners to the very end, the SS had started, in the summer of 1944, to successively abandon those concentration camps located closer to the eastern and western borders. In so-called ‘death marches’, prisoners previously held at the large concentration camps and their broad surrounding network of outlying subcamps (numbering some 500 in all) were moved to the German interior. Due to their state of extreme physical weakness, tens of thousands of the prisoners died just from the transports alone, which they had to endure on foot or in open coal wagons. In addition to this, the SS guards murdered anyone too frail or too sick to march.

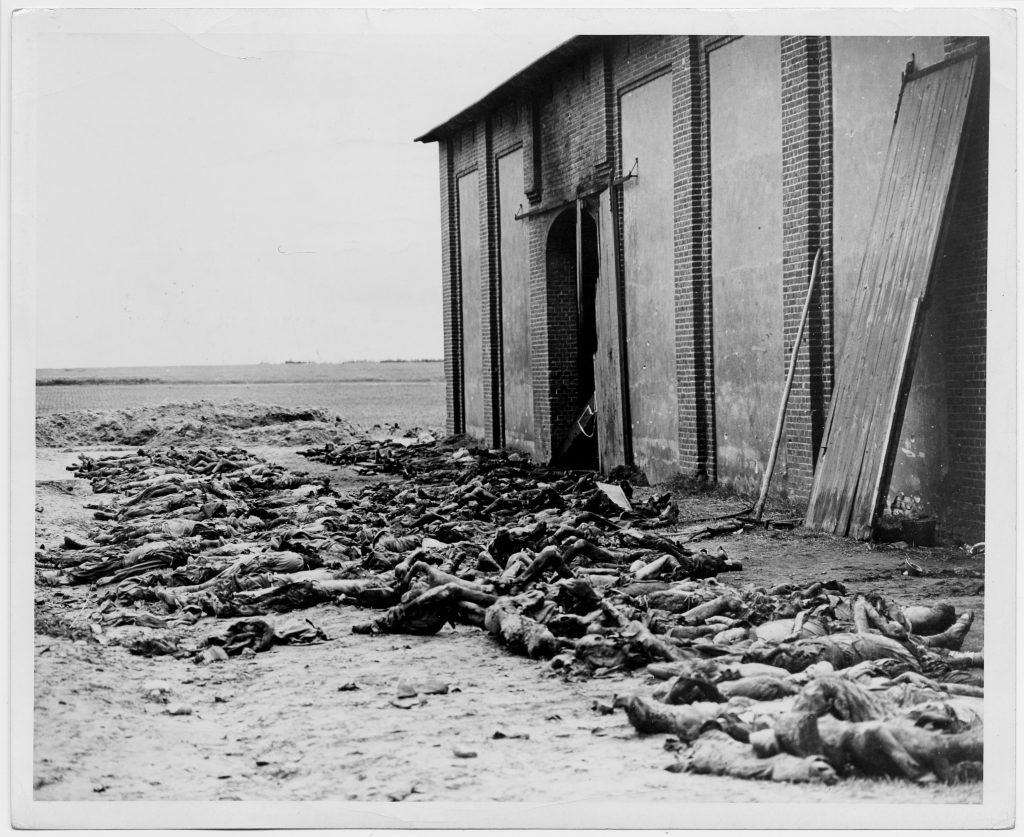

In the course of these evacuation movements and the breakdown of order in the Nazi regime in general, particularly cruel, sometimes apocalyptic, so-called ‘final phase crimes’ (Endphaseverbrechen) occurred throughout Germany between March and May 1945. Members of the SS, the Wehrmacht, the Volkssturm (the Nazis’ newly formed home-defence militia), and various Nazi Party organizations murdered not merely prisoners of concentration camps and prison camps, but also Allied POWs, forced labourers from occupied territories, and Wehrmacht deserters, often in the most sadistic circumstances. To this day, it remains impossible to determine the exact number of all ‘final phase’ victims. What we do know is that by the close of 1944 some 714,000 people were interned in German concentration camps. It is estimated that at least a quarter of a million of them – men, women, and children – died before the end of the war.

Prisoners of the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp murdered by SS men, Wehrmacht soldiers, and members of other Nazi organizations on 13 April 1945 in a field barn outside Isenschnibbe/Gardelegen © DHM

Bodies of prisoners evacuated from the Gross-Rosen concentration camp after the massacre of Abtnaundorf/Leipzig on 18 April 1945 © DHM

Survival

Concentration camp prisoners had especially low chances of coming out of the war alive: conservative estimates state that one in three prisoners (that figure is probably higher, however) in detention at the start of 1945 lost their lives before their camp’s liberation and before the armistice on 8 May 1945. The Jewish girl Sheindi Ehrenwald was not one of them – she lived. Until the afternoon of that day, she had been dismantling vital machinery at an armaments factory in Nuremberg, the Diehl GmbH plant, on the orders of the SS. The machinery was to be loaded onto wagons and transported away. But on the day of the armistice, the SS guards themselves climbed into the wagons and were driven away, and the prisoners found themselves, all of a sudden, free.

For the previous nine months Sheindi had feared for her life locked away in the Peterswaldau camp for women (in what is now Pieszyce in the Lower Silesian province of Poland), a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp. She was put to work as a forced labourer in the Diehl factory, working on the assembly line and in the testing department, manufacturing time fuses for grenades. In summer 1944, the management at Diehl had sent a request to the SS for slave labourers from Auschwitz-Birkenau. As a so-called ‘depot prisoner’, Sheindi was one of hundreds of (mostly Hungarian) women who were kept alive to satisfy German industry’s need for forced laborers in vital sectors of the war effort, and who were not – as their parents, grandparents, younger siblings, and other relatives – ‘exterminated’ in the gas chambers immediately upon arrival. It was in this role as a ‘depot prisoner’ that Sheindi was sent on to Peterswaldau.

And it was there, in Peterswaldau, at the start of 1945, that Sheindi decided to copy the badly damaged remains of her diary, which she had dared to smuggle out of the Jewish ghetto in Hungary and bring with her to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp and back out again. At this point in time, Auschwitz-Birkenau was being evacuated and long rows of prisoners could be seen on arduous death marches through Lower Silesia, including past Peterswaldau. From the Peterswaldau camp it was possible to see the bodies of those who had died along the way, cast into ditches along the side of the road. In early February, the SS also began to abandon the Gross-Rosen camp and about half of the 90,000 prisoners last accounted for there were deported to other concentration camps, mainly to Buchenwald.

But not all subcamps were dissolved and evacuated. In the end, some 35 smaller camps remained populated and were liberated by soldiers of the Red Army on 8–9 May. Peterswaldau was, as it turned out, one of them. By writing up her diary onto fresh paper, Sheindi put herself in mortal danger: had she been caught with the pages on her, she too would have been murdered. But preserving her diary impressions gave her one more reason to live her experiences through to the end and survive. These diary transcripts in the author’s own hand have been on show within the permanent exhibition at the Deutsches Historisches Museum since January 2020, where they are accompanied by a display on Sheindi Ehrenwald’s experiences. Some extracts are also featured in a blog story on this website. Today Sheindi lives in Jerusalem; she is a mother and grandmother. Her new life began on 8 May 1945.

For many survivors, May 8 did not put an end to the war. Nor does it mark what Germans refer to as ‘Hour Zero’ (Stunde Null), a term repeatedly used in the forties and fifties – in both East and West – to represent the turning of a page and start of an entirely new chapter in German history. Nevertheless, after many years of controversy surrounding its interpretation, this day has become a point of remembrance for the mass suffering, for the numerous acts of liberation and various new beginnings in Germany and in Europe as a whole. It symbolizes the epochal caesura in world history that was 1945.