The Stone Cross from Cape Cross – Three countries, three histories, one past

On 7 June, the symposium on the Stone Cross from Cape Cross is being held at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. Dr. Claudia Buchwald has been working on both the content development and organization of this conference. Writing for the DHM blog, she traces the history of the Stone Cross, outlines the different perspectives on the object, and explains why the DHM is hosting this symposium.

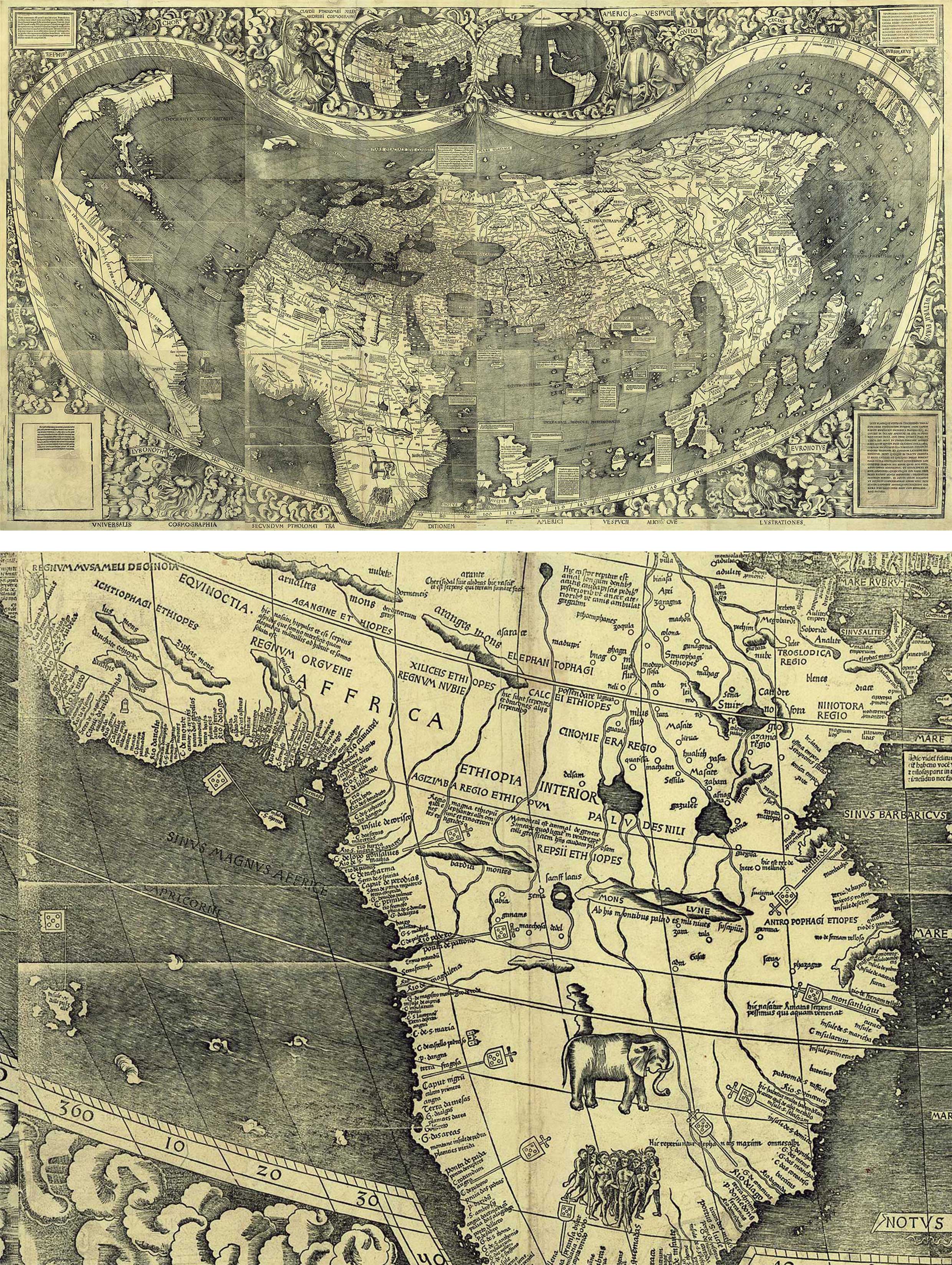

The Stone Cross of Cape Cross: once considered to be such an important landmark that it features on old maps of the world. Its history begins with the great voyages of discovery undertaken in the early modern period. Diogo Cão was sent by the Portuguese king to sail along the West African coastline in search of a sea route to India. For Europeans, India was synonymous with the promise of lucrative trade in spices, silks, and slaves; a sea route, meanwhile, opened up the prospect of “discovering” and colonizing faraway lands as part of a Christianizing mission.

World Map, Martin Waldseemüller, c. 1500

A number of limestone columns with cross attachments, adorned with the Portuguese coat of arms and inscriptions, were erected along the coast. This type of structure, known as a padrão, asserted Portuguese territorial claims while also serving as a navigational aid. In 1486, Cão had a padrão erected on the coast of present-day Namibia. The location was duly named Cabo de Padrão.

The stone grew weather-worn over the centuries, the cross fell into a tilted position and so was no longer easily visible from the ocean. It was occasionally sighted from passing ships. Gottlieb Becker, the German captain of the “Falke” cruiser, discovered the Stone Cross almost by chance while conducting a marine survey in 1893. He gave the order for the object to be brought on board, then had it shipped to Kiel (the naval base of the German Reich). Since 1884, the region had belonged to “German South West Africa” and therefore formed part of the German colonial empire.

For private companies, “German South West Africa” was a promised land of copper, diamonds, guano, and profits from seal-hunting, while for settlers it offered the prospect of land for cattle rearing. The territory was also an opportunity for Germany’s rulers to indulge in the Wilhelmine era’s great power fantasies. The Stone Cross was displayed at the Kaiser’s prestigious Institute and Museum for Oceanography in Berlin as part of the propaganda surrounding the German ruler’s beloved navy. During this period, Kaiser Wilhelm II also gave the order for a new stone cross to be erected on the site (since Germanized as “Kreuzkap”), with a design featuring the imperial eagle and a German-language inscription. The original Stone Cross was eventually moved to the Zeughaus on Unter den Linden, where it has been displayed as part of the permanent exhibition since 2006.

Stone Cross (Padrão) of Cape Cross , 1486 © DHM

Asymmetrical colonial encounters

This is the story so far – at least, from a Eurocentric perspective. Absent from this account are the native population’s side of the story and the significance of the history tied up with the Stone Cross, including the dramatic consequences of colonization. In today’s postcolonial era, African states are demanding that this past be reappraised, while simultaneously liberating themselves from Eurocentric powers of historical interpretation. In recent years, academics have worked towards revealing the asymmetries and complexity of colonial encounters, while also documenting the agency of local rulers – both in terms of the room for manoeuvre they had under German rule and their acts of rebellion against it. Museums have explored these themes, including very recently at the Deutsches Historisches Museum with the German Colonialism – Fragments Past and Present exhibition.

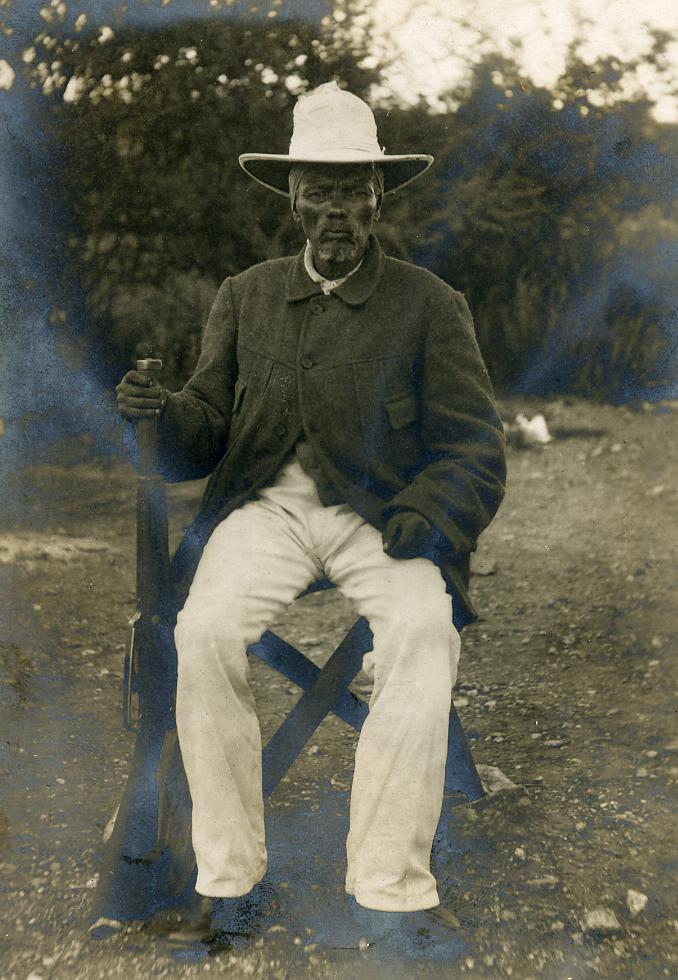

Nevertheless, there remain a great many open questions. It is hard for us to imagine the first encounters between the Herero people and European seafarers, when the two groups exchanged knives, calabash, and raw materials. In Germany, little is known about Samuel Maharero and Hendrik Witbooi, the respective leaders of the Herero and Nama, who originally formed alliances with the colonial rulers before rising up and waging war against German rule and land ownership. By contrast, Lothar von Trothas’ campaign of destruction against the Herero – the survivors of which then perished of thirst in the desert – and the internment of Herero and Nama people in concentration camps have attained widespread notoriety. Tens of thousands of men, women, and children died. This tragic climax of the rebellion has since been declared a genocide. UNESCO includes Hendrik Witbooi’s diaries, known as the Witbooi Papers, in its list of world documentary heritage. The public debate surrounding the politics of memory has gained momentum.

Nama-Leader Hendrik Witbooi in Rehoboth, c. 1900 © DHM

In parallel to these developments, European museums are having to respond to another discussion: the controversy surrounding the restitution of colonial objects. In 2017, the French President Emmanuel Macron announced in Burkina Faso his intention of surrendering all African objects held in French museums. The German Museum Association recently issued guidelines on how to deal with collections that originate from colonial contexts. Since 1 June 2017, the German government has been in receipt of a diplomatic note, in which Namibia demands the restitution of the Stone Cross – itself a sign of the shift that has taken place in dealing with the two countries’ shared history.

Historical justice

Colonial objects represent their history. The Stone Cross’s history is well known – but it is also necessary to examine the various perspectives it elicits. These different perspectives need to be put side by side, negotiated, and their significance for the Stone Cross established. Related to this are questions regarding presentation in exhibitions and an approach to these objects that encompasses different continents. Yet every object is different, each history special. The Stone Cross from Cape Cross is not an African artwork. This in turn raises the question of how descendants in Europe and Africa can engage in dialogue that does historical justice to the object. Even through the discussion is not intended to be based on the premises of international law, it will take into consideration the possibility of the Stone Cross being returned to Namibia. These questions will be the central themes explored at the Deutsche Historisches Museum’s symposium, which represents an opportunity for exchanging a wide variety of different perspectives.

Cape Cross, Namibia, 2018 © DHM