Lucky Pigs and Busy Bees

In the latest in our series “What’s That For?”, Christin Noll, a staff member in the Deutsches Historisches Museum`s education and outreach department, explores why animal and nature symbols have played such a key role in representations of saving, and how this has changed over the years.

Today, savings boxes come in all shapes and sizes. In Germany, the piggy bank is probably the best-known and most popular. But the relation between pigs and savings is not immediately clear. Pigs, it’s fair to say, are not particularly thrifty, and neither are they known to make interest payments. Maybe a pig can be regarded as a good investment – once upon a time, a well-fattened pig could feed an entire family for quite some time. There is also the fact that in Germany, the frugal pig is also regarded as a lucky charm.

Inklusive Kommunikationsstation in der Ausstellung “Sparen”, Berlin, 2018 © Deutsches Historisches Museum

However, it was only in the first half of the twentieth century that pigs became associated with saving your spare change. Previously, the squirrel was more popular as a way of teaching children to save their pennies. Take care of the pennies and bigger sums will come of their own accord, suggest several popular German sayings, for example: “slow and steady feeds the squirrel” (“Mühsam ernährt sich das Eichhörnchen”). Making careful provision for one’s future is another lesson that can be learned from the squirrel, which carefully stores food for the winter months ahead.

Think ahead and save – you’ll reap the rewards

But ultimately, neither pig nor squirrel have all that much to do with savings. Institutionalized saving, which seeks to generate returns by earning interest, does not really exist in nature. Advertisements and popular sayings may suggest the process is natural and logical, but in reality it is nothing of the sort. However, this kind of naturalization is precisely the reason why nature symbols were common in saving advertisements for so many years.

Spardose der Sparkasse des Plauenschen Grundes Freital mit Beschriftung »Mit Sparsamkeit und Bienenfleiss erringst Du Dir den höchsten Preis« Deutschland, 1920–1930 © Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband e.V., Sparkassenhistorisches Dokumentationszentrum Bonn

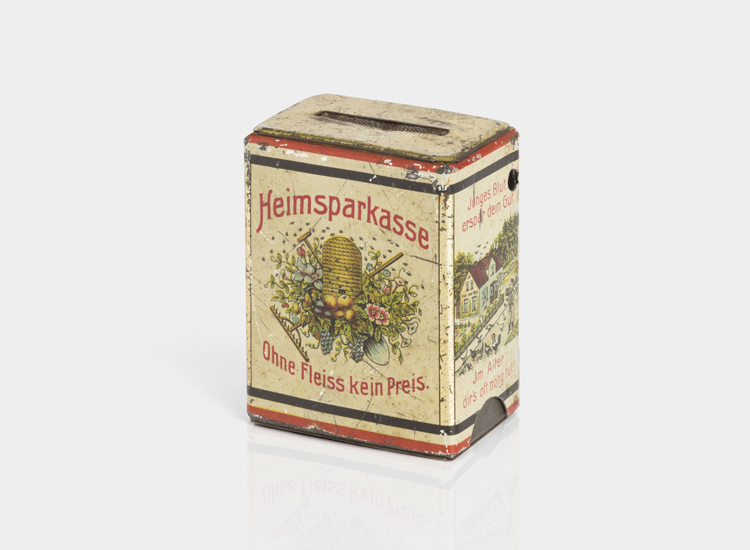

In addition to the squirrel, other images were also used for savings posters and tins in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These included numerous agricultural images, including many with bees, an animal regarded as particularly “busy” and industriousness. Images of harvesting imply that it is possible to plan one’s own financial situation, and hold out the prospect of reaping rewards through careful saving.

In reality, German savers have lost their nest eggs time and again. War bonds sold to finance the First World War turned out to be a very poor investment. In the early 1920s, hyperinflation and the subsequent currency reform wiped out the savings of large swathes of the population. Nonetheless, agricultural motifs used to advertise saving were even more popular under the Nazi regime, which ruled the country between 1933 and 1945. Under National Socialism, references to nature served an ideological function: advertisements equated interest payments with the hard-won harvest, thus making a clear distinction between ordinary interest payments and what was termed “Jewish finance capitalism”.

Heimsparbüchse mit Sprüchen und Bildmotiven, um 1900 © Historisches Archiv der Erzgebirgssparkasse Schwarzenberg, Foto: Thomas Bruns

Images of harvesting can be found on the posters of savings banks well into the 1950s. Only in the second half of the twentieth century does this kind of nature symbolism finally disappear. In its place, the pig increasingly makes an appearance, symbolizing good luck and happiness in saving.