The Savings Book of Anna Gleiss

Among the objects on display in the exhibition “Saving – The History of a German Virtue” is the apparently unremarkable savings book of Anna Sophia Henriette Gleiss. How can this be an important document of the early savings movement? Maike Schimanowski explains in our blog section “What’s That For”?

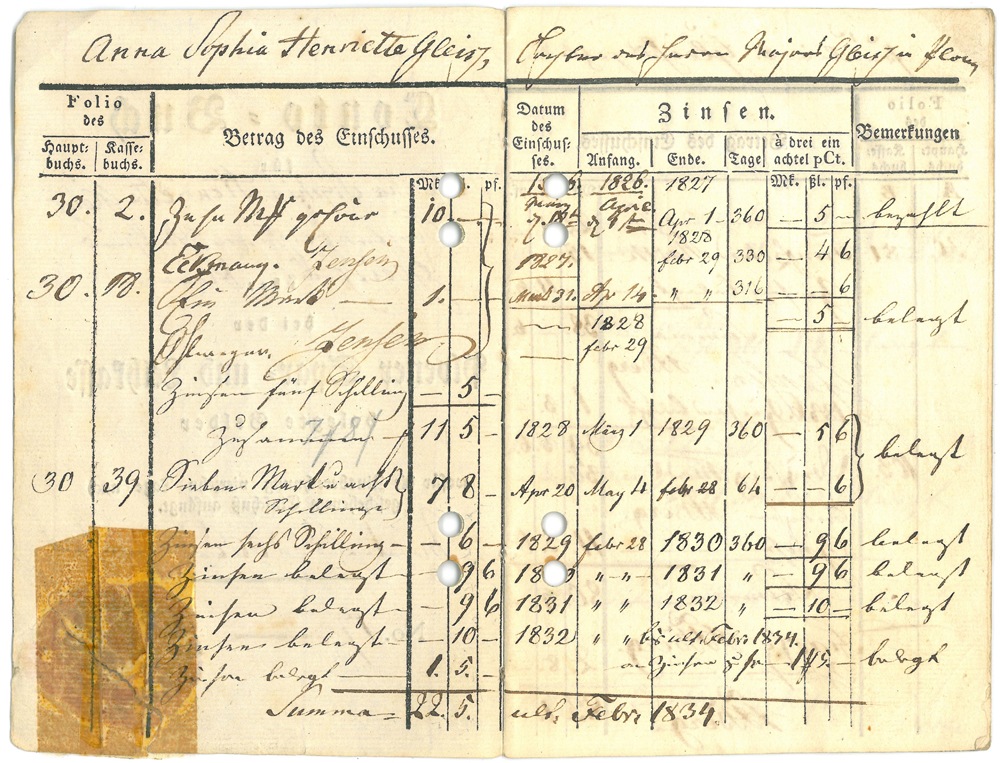

What can the little Anna Sophia Henriette von Gleiss have thought when she was given a savings book by her father at the age of ten? The sum of 10 marks was already entered in the book; imagine all the things she could have bought with that, back in 1826! Yet she saved it, and her father, one of the founding members of the Plön Savings Bank, paid money into her account every year.

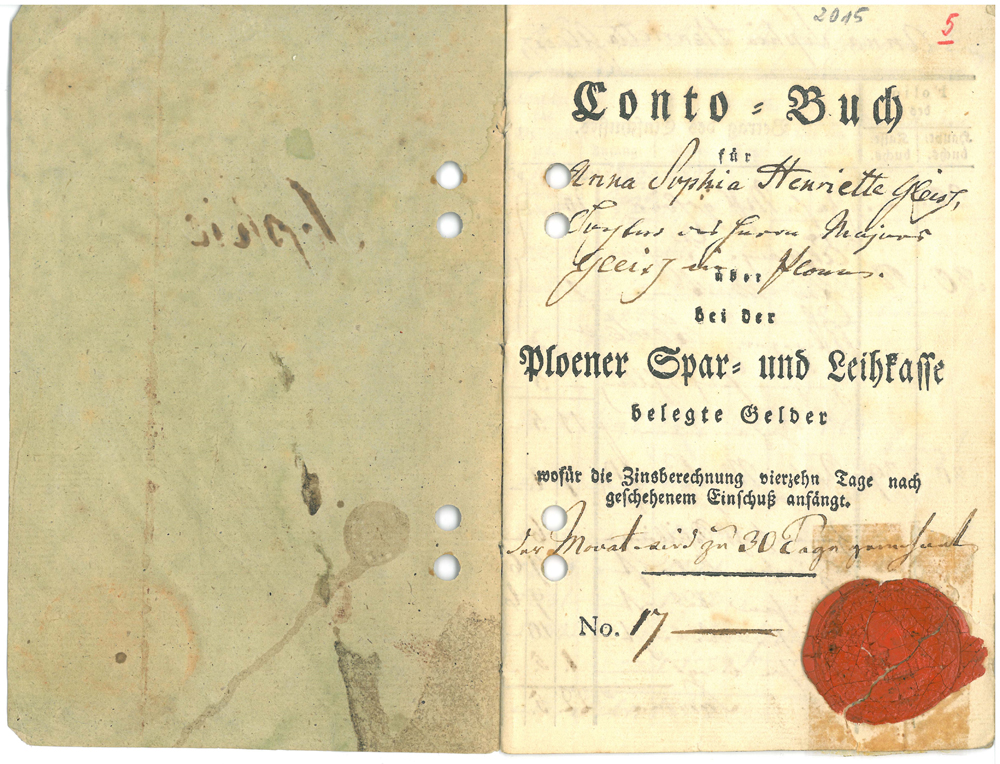

Savings book of the Savings and Lending Bank of Plön for Anna Sophia Henriette Gleiss, 1826–1847 © Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband e.V., Sparkassenhistorisches Dokumentationszentrum

When the Savings Bank was set up by private shareholders in 1826, in what was then the Danish Duchy of Schleswig-Holstein-Plön, the “Plan for the Foundation of a Savings and Lending Bank in the Town of Plön” stated that:

“The Savings Bank will give every inhabitant of the town of Ploen and the surrounding area, regardless of age and social status, the opportunity to deposit his savings, no matter how small.”[1]

Thus, the bank specifically welcomed low-earners, tradesmen, and other less-well-off people. Instead of hoarding their savings – in other words, simply putting them away and leaving them untouched – they were encouraged to deposit them with an institution. Opening a savings account with a bank had the great advantage of earning interest on one’s money.

Reading between the lines of the founding document, it is clear its authors were convinced that there were a great many low-wage workers – “poor people” – who earned a financial surplus, which, up to now, they had simply kept under the mattress. This assumption, seen in the founding constitutions of many early savings banks, shows that poverty was now no longer simply regarded as a God-given fate. Immanuel Kant had declared that man, being endowed with reason, was capable of taking responsibility for his own life and emancipating himself from misfortune through his own efforts; it followed, therefore, that he could make financial provision for himself. Furthermore, people increasingly now believed it should be possible to rise up the social ladder by practising the bourgeois virtues of hard work and thrift. Support for the poorer echelons of society was based on a fundamental expectation, “whereby it is hoped that they [the poorer classes] will benefit from the amenity thus afforded them to better their situation and become important and valuable assets to the state through hard work and thrift”.[2]

In 1836, when Anna was just 16, her mother died after a serious illness. From now on, Anna probably had to keep house for her father and siblings. Then, in March of the same year, her father died too. Caspar Diedrich von Gleiss, Inspector of Customs, was carried off by consumption – tuberculosis of the lungs – in just eight days. Anna and her siblings were now placed for two years under the guardianship of the town of Neustadt in Holstein, which provided them with financial support. At the time, the town was experiencing an economic boom, thanks to its shipping business and grain trade.

When the guardianship ended in 1838, the Gleiss children were left to stand on their own feet. Nevertheless, it was nearly 10 years before Anna Sophia Henriette von Gleiss was forced to call on her “emergency savings”, which on 7 July 1847 amounted to 98.90 marks. Fraulein Gleiss was 31 years old and had meanwhile probably been living as a spinster in the ever more prosperous Neustadt. In the ten years since the death of her father, she had not been able to deposit a single mark from her wages in the savings account. We can be sure that the almost one-hundred marks had to be carefully rationed.

Savings book of the Savings and Lending Bank of Plön for Anna Sophia Henriette Gleiss, 1826–1847 © Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband e.V., Sparkassenhistorisches Dokumentationszentrum

After the Paris February Revolution of 1848, political unrest swept the whole of Europe, with the March Revolution breaking out in many German cities. In the territories of the Danish state, too, events moved quickly: in July 1848 the First Schleswig War began in the states of Schleswig and Holstein, between Germany, under the sway of the Nationalist Movement, and the Kingdom of Denmark. Whether by necessity, luck, or caution, Anna Gleiss had withdrawn her money from the bank and closed the account one year before the three-year-long war began. She received interest of 35 marks and 10 schillings. Her small wages did not allow her to keep the account open. With its closure, all trace of Anna Henriette Sophie Gleiss disappeared.

References

[1] Stadtarchiv Plön, Akte 701: P.S. Schönfeldt (königl. privil. Buchdrucker): Plan zur Gründung einer Spar- und Leih-Kasse in der Stadt Ploen, Itzehoe 1825, S. 5 § 7.

[2] Zit. Nach Josef Wysocki: Untersuchungen zur Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte der deutschen Sparkassen im 19. Jahrhundert (Forschungsberichte der Gesellschaft zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung über das Spar- und Girowesen e.V., Bd. 11), Stuttgart 1980, S. 198.