The Kindertransporte, 1938–39

In response to reports of the Kristallnacht pogroms (the so-called ‘Night of the Broken Glass’) – the government-led attacks on Jews in November 1933 – many countries eased their strict entry requirements for Jewish refugees and announced their preparedness to accept children and teenagers up to the age of seventeen. The Leo Baeck Institute in New York is currently presenting an exhibition on the so-called Kindertransporte (Children’s Transports) which were carried out around that time. For the DHM Blog, Miriam Bistrovic, head of the Leo Baeck Institute’s Berlin office, writes about the largest action of this kind, the relocation of 10,000 children to England, where they survived the Holocaust.

My child has gone. At six in the morning we brought our boy to Schlesisches Tor to be taken on the Kindertransport to England. How horrifying it was! And the people I met there this morning! A colleague in deep mourning – her husband died three days after being released from the concentration camp. She is sending her boy away. A patient of mine brings her little four-year-old daughter.[1] —Hertha Nathorff, March 2, 1939

In response to international reports of the Kristallnacht pogroms of November 1938, many countries eased their strict immigration restrictions for Jewish refugees. Britain, along with Switzerland, Holland, Belgium, France and Sweden, said it was prepared to accept children and teenagers up to the age of seventeen from the German Reich and its annexed regions, as well as from countries threatened with conquest. Within a few days, the first Kindertransporte had been organized. The British-based Movement for the Care of Children from Germany (later renamed the Refugee Children’s Movement) worked closely with private individuals, the Reichsvertretung der Juden in Deutschland (National Representation of German Jews) and the Jewish Community in Vienna to compile names and raise funds. The British government insisted on a surety of fifty pounds per child,[2] to avoid excess costs and to pay for the accommodation and ultimate repatriation of the children taken into care.

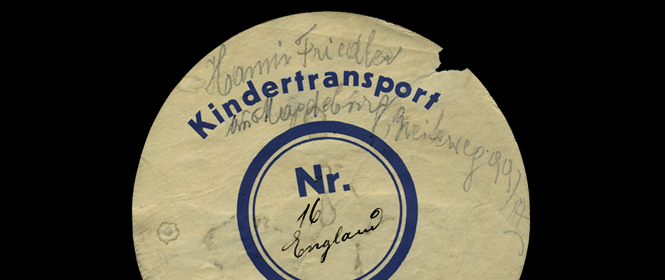

Kennungsmarke Hilfsverein der Deutschen Juden, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, AR

The Kindertransporte from Germany were organized centrally. Children from eastern, south-eastern and northern Germany were assembled in Berlin or joined the trains at railway stations en route. Children from south-western and southern Germany were assembled in Frankfurt am Main.

After highly emotional scenes at the departure of the first Kindertransporte, the authorities were keen to avoid further public emotional outbursts, and parents were forbidden from saying goodbye to their children on station platforms. In a diary entry for March 2, 1939, Hertha Nathorff describes the emotions that the parents experienced:

Soon we must say goodbye. The children are to be brought to the train in groups. Parents are forbidden to accompany them to the station. I kiss my son and whisper ‘At Zoo Station, look out the window’ – nothing more. […] I jump in the car, race to Zoo Station, buy a platform ticket, dash up the stairs and arrive before the train. […] The platform is quite empty and no-one stops me from approaching the train. And – my boy looks out the window and – sees his mother again – ‘I’ve got a great seat, Mummy’, he chirps in his childish voice. […] Once more I hold my son’s beloved hand, he leans out of the window – another kiss and the train snatches him away from me.[3]

The trains connected with the ferry to England at Hook of Holland, Hamburg or Bremen. Most of the boats arrived in Harwich, some in Southampton. The first Kindertransport, with almost 200 children from Berlin on board, arrived in Harwich on the morning of December 2, 1938.

At first, the children selected were mainly those judged to be in particular need of protection: orphans, children with parents under arrest, adolescents threatened with imprisonment, and stateless children at risk of deportation.

The bare minimum of personal belongings could be taken on the journey. Horst Rosenberg was thirteen years old when he left Frankfurt on a Kindertransport on February 7, 1939. He made a detailed, two-page list of his meagre luggage: clothes for little more than a week, some warm winter clothing, sports gear, writing materials and his camera. That was all he was allowed to take on his journey to a strange land. Even a gift from his godparents, a drinking cup, was removed.[4]

The time families were given to prepare was very limited. The passport belonging to Anneliese Erlanger, a fourteen-year-old girl, was issued on August 8, 1939. The stamp shows that she had to leave Germany by the end of that month. She arrived in Harwich on August 25, 1939. Her sister Inge, three years younger, could not obtain a place and was left behind in Germany, along with her widowed mother Emma Erlanger. Both were murdered in 1942.[5]

After reaching England, the newly arrived children and teenagers were distributed to care homes, foster parents and reception centres. Before leaving Germany, many had been told to adapt quickly, to be obedient and show good manners. What caused great anxiety to their parents was the question of how their children would be looked after by strangers. A steady stream of postcards and letters was the only way for families to learn of their children’s welfare and try to keep their spirits up. At sixteen, Heinz Ludwig Katscher was among the oldest children on the Kindertransport. Like many others, he found it hard to get used to the strange surroundings and the new language, despite great efforts. His parents Alfred and Leopoldine were aware of this when they answered his cards and letters on December 27, 1938, assuring him they would write daily from then on:

‘You have done terribly well so far, and your lovely letters paint us a picture of some of your present life. Little one, if you are overcome with homesickness again, please know that we think of you constantly, day and night.’[6]

Some months later, Heinz’s sister Liane was able to follow him to England. But the parents’ emigration plans came to nothing. Their hopes of seeing their children again would never be fulfilled. They were both murdered in Maly Trostinez, an extermination camp close to Minsk.

The last official Kindertransport reached England on September 2, 1939. The German attack on Poland the previous day marked the outbreak of the Second World War, and also ended the large-scale campaign which brought almost 10,000 children to England. They escaped the Holocaust, often as the only survivors of their entire families.

Sources

[1] Excerpt from Hertha Nathorff’s diary, March 2, 1939, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, Hertha Nathorff, Memoir, Reichstagsbrandt, ME 460.

[2] In 1938, this was the equivalent of around 600 Reichsmarks (see Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, based on currency equivalency tables from the German Central Bank, annex II).

[3] Excerpt from Hertha Nathorff’s diary, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, Hertha Nathorff, Memoir, Reichstagsbrandt [Reichstag Fire], ME 460.

[4] Luggage of Horst Rosenberg, February 6, 1939, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, Horst Rosenberg Collection AR 25506 box 1, folder 2; exit permit for Horst Rosenberg, February 3, 1939, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, Horst Rosenberg Collection, AR 25506 box 1, folder 2.

[5] Anneliese Erlanger passport, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, Anna Erlanger Rotenberg Collection AR 25576, box 1, folder 4; photograph of Anneliese and Inge Erlanger, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, Anna Erlanger Rotenberg Collection AR 25576, box 1, folder 3.

[6] Letter from Alfred and Leopoldine Katscher to Heinz Ludwig Katscher, December 27, 1938, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, Ludwig Katscher Collection, AR 6336, box 1, folder A.

[2] Paul Steiner’s diary, Paul Steiner Collection AR 25208, Box 1, Folder 7, http://www.lbi.org/digibaeck/results/?qtype=pid&term=476154 (last downloaded 12 February 2018).

Dr. Miriam BistrovicDr. Miriam Bistrovic is a historian and art historian. Since late 2013, she has headed the Berlin branch of the Leo-Baeck-Institute New York|Berlin, coordinating the organization’s activities in Germany. Her most recent project is the online calendar and the related touring exhibition, “1938Projekt – Posts from the Past”. |