The ‘Maximilian Crossbow’

Felix Jaeger | 28 October 2019

The DHM’s collection of crossbows is one of the most important in the world. There is little doubt that two of its especially valuable pieces originate from the private collection of Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519). January of this year marked the 500th anniversary of the emperor’s death – reason enough for Felix Jaeger, academic researcher and curator of the exhibition The Crossbow – Terror and Beauty, to take a closer look at the objects.

Kaiser Maximilian I. im Privatornat, Bernhard Strigel, Memmingen, 1496 © DHM

Known for his overhaul of the Holy Roman Empire, Maximilian I was at least as passionate about hunting as he was about administrative reform. His hunting weapon of choice was the crossbow.The weapon’s advantages over the traditional bow of yew or ash are obvious: once the crossbow was drawn, the hunter could take as long as he needed to take aim at his quarry. The crossbow also has a number of advantages over the sort of early firearms available in Maximilian’s day. Since it fired near-noiselessly and produced neither smoke nor odours, the crossbow could be operated without scaring off other game.

Who on Earth’s Going to Eat All This?!

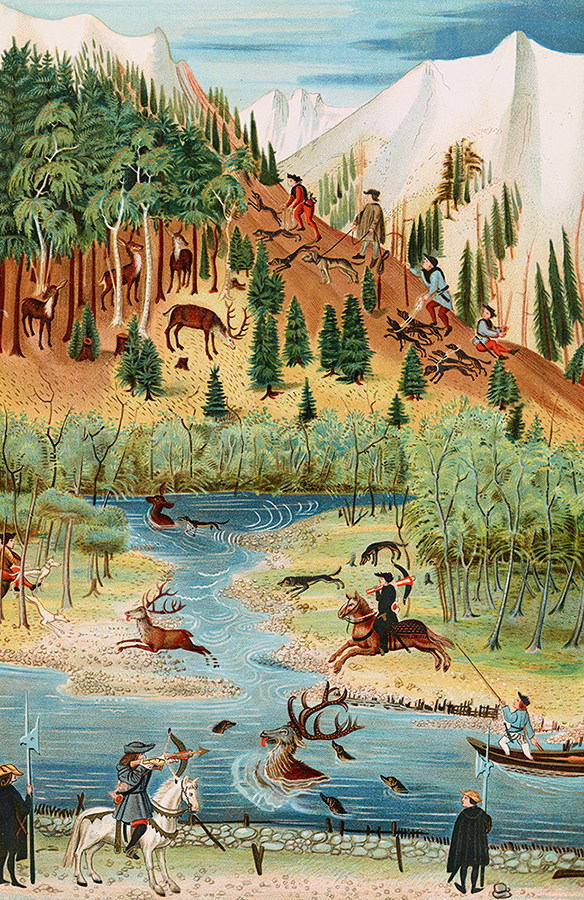

Courtly hunting was an important status symbol for the aristocracy in the early modern era. Nobles found it a useful way to distinguish themselves further from the commoners. However, courtly ‘chases’ were also used by rulers to entertain visiting dignitaries as part of the programme of events accompanying diplomatic negotiations. When an important visitor was at court, it was not uncommon for hundreds of animals to meet their end in a single day (some having been released into the wild in preparation for the hunt). Maximilian was no exception: he is said to have shot ten stags in half a day, downed 100 ducks with just 105 bolts on another occasion, and felled 26 hares in quick succession without missing a single one. A true master huntsman, in other words?

Jörg Kölderer, Hirschjagd auf der Langenwiese bei Innsbruck. Abb. aus der Faksimileausgabe des Jagdbuchs Kaiser Maximilians I. von Michael Mayr, Innsbruck 1901 © DHM

Media for Political Ends

Whether these numbers are accurate, or more a reflection of the emperor’s wishful thinking, is of secondary importance. What is important – not least for Maximilian himself – is that these are the figures recorded for posterity. A masterful promoter of his own self-image, Maximilian was one of the first monarchs to grasp the importance of the new printing technology, and proved adept at constructing a legacy around his own person. In a sense, therefore, the chivalric epics Theuerdank and the Weisskunig – glorified retellings of episodes from Maximilian’s life – can be regarded as autobiographical works. This artistic articulation of Maximilian’s status as emperor culminated in 1517 with the creation of a monumental woodcut print, the Ehrenpforte (Triumphal Arch). By having his conception of imperial authority lent visual form, and the image disseminated throughout the Holy Roman Empire, Maximilian was able to reach beyond the literate minority in a manner accessible to each and every one of his subjects.

Der Weißkunig zu Pferd auf der Jagd mit Gabelbolzen. Abbildung Nr. 40 aus dem Weißkunig © DHM

A visual legacy of a similar kind, albeit intended for a purely private audience, is the depiction of a hunter on one of the two crossbows (seen on the front of the bow limbs). On the right, the hunter takes aim at a stag with his crossbow, while on the left, he brandishes a pike in front of a charging wild boar. The figures in these two scenes bear a striking similarity to contemporary portrayals of Maximilian in hunting garb. Since it is likely that the depictions were personally commissioned by the emperor, it seems reasonable to assume that he wanted to be immortalized this way as well.

Jagddarstellung auf dem Bogenrücken einer „Maximiliansarmbrust“, Aragón und Innsbruck, 1508–1515 © DHM

More Than Just a Weapon

The limbs of each bow of the ‘Maximilian crossbows’ are richly decorated, not just with engravings of the kind described above, but also with etched inscriptions on the face side (rear). The inscriptions are in Latin and capture the profound religiosity of early 16th-century society. Even a mighty ruler with as lofty a title as the Holy Roman Emperor remained beholden to the deeply entrenched piety of the age. ‘O MATER DEI MEMENTO MEI’ – Mother of God, remember me – is an expression of the monarch’s humble desire for divine grace. ‘SPERO LVCEM’ – I hope for light (Job 17:12) – also serves to convey this deep faith in God’s favour. ‘SI DEVS PRO NOBIS QVIS CONT[RA] NOS’ – If God be for us, who can be against us? – is a biblical quotation (Romans 8:31) that, seen in the context of the Habsburgs’ significance during this period, could be interpreted as a statement of dynastic self-confidence intended for transmission to subsequent generations. Incidentally, similar inscriptions also appear on the five other surviving ‘Maximilian crossbows’ held at the Musée de l’Armée in Paris and the Imperial Armoury in Vienna.

![„SI DEVS PRO NOBIS QVIS CONT[RA] NOS“ – Geätzte Inschrift auf dem Bogenbauch einer „Maximiliansarmbrust“, Aragón und Innsbruck, 1508–1515 © DHM](/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/W82_1_Bogen_innen.jpg)

„SI DEVS PRO NOBIS QVIS CONT[RA] NOS“ – Geätzte Inschrift auf dem Bogenbauch einer „Maximiliansarmbrust“, Aragón und Innsbruck, 1508–1515 © DHM

High-Tech, 16th Century-Style

Using a reproduction of one of the two crossbows, it was possible to put the operational performance of these early-modern hunting weapons to the test. The crossbow’s tensile weight is around 415 kg, so drawing the weapon would theoretically require five adults to hang with their full bodyweight from the bowstring. The task was simplified somewhat by using highly efficient rack-and-pinion cranequins. Fired at a 45° angle, the weapon was able to achieve an average range of approximately 250 metres – more than twice the length of a football pitch. However, it was only possible to strike targets with lethal precision from a maximum distance of about 50 metres.

Eine der „Maximiliansarmbruste“, Aragón und Innsbruck, 1508–1515 © DHM

The experiment demonstrated that the ‘Maximilian crossbows’ were both highly efficient and effective, although the weapons’ real significance derives from their aesthetic form. Above and beyond their function as a hunting weapons, the crossbows served more as expressions of Emperor Maximilian I’s personal desire for artistic representation. Most of all, however, the weapons bear witness to the deep-rooted piety common to all social classes as the late Middle Ages gave way to the early modern era.

Felix JaegerFelix Jaeger is a historian specializing in early-modern military history. Most recently, he has worked as a researcher and curator for the exhibition The Crossbow – Terror and Beauty. |