Hannah Arendt: Only within the Limits of Nature is Freedom Possible

Maike Weisspflug | 14 May 2020

Hannah Arendt is the thinker of the modern age and of political freedom. Which is why she is often quoted in times of turmoil – be they crises or revolutions. In the current corona crisis, Arendt’s reflections on totalitarianism seem vitally relevant once again, in pointing out the political and social dangers of a continuing state of emergency. But this is only a one-sided view of political freedom, as demonstrated by, among other things, the current appropriation of the term among the populist far-right and conspiracy theorists. We are at risk of suffering a much greater loss of freedom, as, in the planetary order of things we are overstepping the limits of nature and thus endangering the very conditions for life between peoples and species.

One of Arendt’s quotes currently much-shared on social media is the ‘dream of the totalitarian police’, which Arendt describes in her book The Origins of Totalitarianism, of ‘a gigantic map’ which one could merely glace at to ‘establish who is related to whom and in what degree of intimacy’. About this ‘modern dream’, Arendt writes: ‘its technical execution is bound to be somewhat difficult’ but ‘not unrealizable’ (p. 434)

By choosing this quote from Arendt’s writings, commentators are of course alluding to the planned use of tracking apps to help contain the pandemic while maintaining citizens’ freedom of movement as far as possible. In an open letter entitled the Contact Tracing Joint Statement, more than 100 scientists and researchers from all over the world warn of ‘large-scale data collection on the population’ and ‘the unprecedented surveillance of society at large’. Yuval Noah Harari also recently pointed out in The Financial Times that finding the way out of a state of emergency is always harder than finding the way into it. He therefore suggests that state surveillance should be countered by empowering well-informed citizens to act in global solidarity.

Is Freedom at Risk?

However, the political attempts to overcome the crisis by no means pose the greatest threat to freedom that this present crisis forebodes. And, more to the point, the threat in question is one we may well face within a reasonably short period of time, with profound political and social ramifications. For Arendt, the desire for total control and domination is not really the main characteristic of totalitarianism. Rather, for her, the core of totalitarian ideology can be distilled in the maxim ‘everything is possible’, the idea that ‘everything that exists is merely a temporary obstacle that superior organization will certainly destroy’ (p. 355), even human nature.

Origins of totalitarianism: installation view from current exhibition. Photo © Gregor Baron

Against this totalitarian fantasy of boundless omnipotence, Arendt sets a concept of freedom that takes into account the limits of action. These limits can vary considerably: the inviolability of others, the recognition of facts or the ‘human condition’, specifically in terms of our concrete actions (our vita active), not merely our thoughts, as creatures adapted to life on planet Earth. Arendt emphasizes again and again that political freedom is only conceivable within these limits set by our fellow human beings and by nature. In view of the corona pandemic and its deeper underlying causes, this may indeed even be a liberating thought.

The Unprecedented Crisis?

If anything, the crisis has shown us with great urgency how vulnerable our societies are and how quickly citizens’ freedoms can hang in the balance. In one respect, the corona pandemic is quite unlike epidemics such as cholera or the plague that have routinely afflicted humans: We know that it was most likely caused by our overreach in the natural world, our encroachment on natural habitats, the expansion of industrial agriculture and, last but not least, man-made climate change. The corona crisis should therefore be seen as a chapter in the unfolding history of a much larger ecological crisis for which unsustainable economic and political practices are responsible. In short: ‘We did it to ourselves.’

Applying Thought against Doomsday

Just as Arendt read Kant and Kafka, but also Homer and Conrad to understand total domination, we ourselves can read Arendt to make sense of our present. Not because writers and philosophers always have eternal truths on demand or can deliver a list of guiding principles for us to follow in our current times. Rather, because they provide the ‘ferment of knowledge’, the fermenta cognitionis as Lessing so beautifully put it, with which we can nourish ourselves. Arendt’s important impulse seems to me to be that she wasn’t so much concerned with doomsday scenarios, even when she was in fact thinking about one form of crisis in modernity after another. She preferred to look for stories that spoke of freedom, of the wonders of acting together and attempting bold new beginnings. Without these stories and without remembering history, Arendt believed, freedom is just as surely lost as under totalitarian oppression. What it all comes down to is how we choose to frame the story.

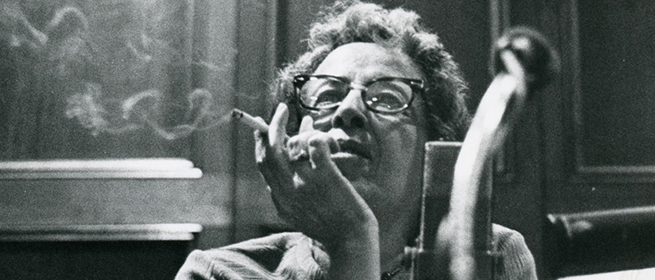

Hannah Arendt at the University of Chicago 1966 © Art Resource, New York, Hannah Arendt Bluecher Literary Trust

Nature and Freedom

The virus makes us sense our limitations. As painful as it is to live with the current government restrictions, the situation also has the potential to make us more sensitive to the limits of what is feasible: socially, politically, and, most importantly, ecologically. For Arendt, all these limits were not limitations on freedom, which we have to accept, for better or worse, but their very precondition. In her eyes, we always act under a certain set of constraints, for we always lack the absolute power to shape nature or other people. Believing otherwise is a dangerous and above all unnecessary illusion. In fact, the current calls for unlimited freedom and the obsessive idea that the coronavirus is just a conspiracy dreamt up by a cabal of elites to control ‘the people’ clearly bear the hallmarks of totalitarian thinking.

Plundering the planet’s resources is not an expression of freedom. We might instead change our dealings with each other so they remain within this planet’s natural limits. Stopping the wanton destruction of nature would, in fact, mean preserving a life of freedom for future generations: not the freedom of unfettered consumerism, but the freedom to act together in shaping the world. Framing the story in this way stresses the truly conservative (as in conservationist) nature of Arendt’s line of thinking – and follows the revolutionary call that lies therein.

Sources

Hannah Arendt: The Origins of Totalitarianism, San Diego/New York/London, 1st printed 1951, reprinted 2016.

Maike Weisspflug: Hannah Arendt. Die Kunst, politisch zu denken, Berlin 2019.

© Privat |

Maike WeißpflugMaike Weisspflug is a political theorist and works as a research fellow at the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin’s natural-history museum. Her book Hannah Arendt. Die Kunst, politisch zu denken was published in 2019 by Matthes & Seitz. |