Fred Stein’s Portraits of Emigrants in Paris

Ulrike Kuschel | 28 April 2021

The exhibition “Report from Exile – Photographs by Fred Stein” shows 40 portraits taken by the photographer in Paris between 1934 and 1939. The curator Ulrike Kuschel describes the circles he moved in and the people of renown he photographed.

In June 1935, around 250 writers from 38 countries gathered in Paris for the First International Writers’ Congress for the Defence of Culture. The autodidact Fred Stein was also there. Today we can no longer establish whether he had a commission or, like so often, he came on his own to photograph the event. Alongside Stein, another photographer who had fled Germany in 1933 was also there to photograph the writers’ congress, Gisèle Freund. Both of them used a Leica camera, which they had each brought with them from Germany. The world’s first 35mm camera – compact and handy – was popular not only with amateurs, but also allowed professional photographers to take inconspicuous snapshots. In this way, Stein was able to work unobtrusively on the periphery of the event and shoot, for example, his iconic photo of Boris Pasternak, surrounded by Ilya Ehrenburg, Gustav Regler and André Malraux, with the used Leica I he had bought in Germany.[i]

Boris Pasternak (seated) at the International Writers’ Congress, behind him Ilya Ehrenburg, Gustav Regler and André Malraux (with his back to the camera), Paris, June 1935 © Stanfordville, NY, Fred Stein Archive

Fred Stein, who had actually studied law and fled Germany in autumn 1933, when, “due to the wholesale arrests of like-minded people it was to be feared that [he] would be caught up in the impending trials”,[ii] began to work as a portrait and press photographer in Paris in February 1934. Here he photographed numerous well-known intellectuals and opponents of the Nazi regime. Of the 33 particularly prominent regime antagonists whose names were on the German Reich’s first list of citizens to be expatriated, published in August 1933,[iii] he photographed at least nine, some of them, however, only later in New York. How was it possible that a young self-taught photographer – Stein was 24 years old when he fled Germany – was able to capture the image of all these luminaries in Paris?

A closer look at the political and social activities of the men and women photographed by Stein shows that many of them belonged to two different exile organisations that were founded in Paris in 1933: the communist-dominated Schutzverband deutscher Schriftsteller im Ausland (Association of German Writers in Exile) and the Verband deutscher Journalisten in der Emigration (Association of German Journalists in Exile). Stein, who had become of member of the journalists’ association in 1935, was elected to its board in 1937. Later, in 1965, he explained to Werner Berthold, director of the German Exile Archive, that the reason he was able to make the “probably […] largest collection of photos of such [emigrant] authors that a photographer himself had ever made”[iv] was that as treasurer of the association, he had had “personal contact with the authors”.[v]

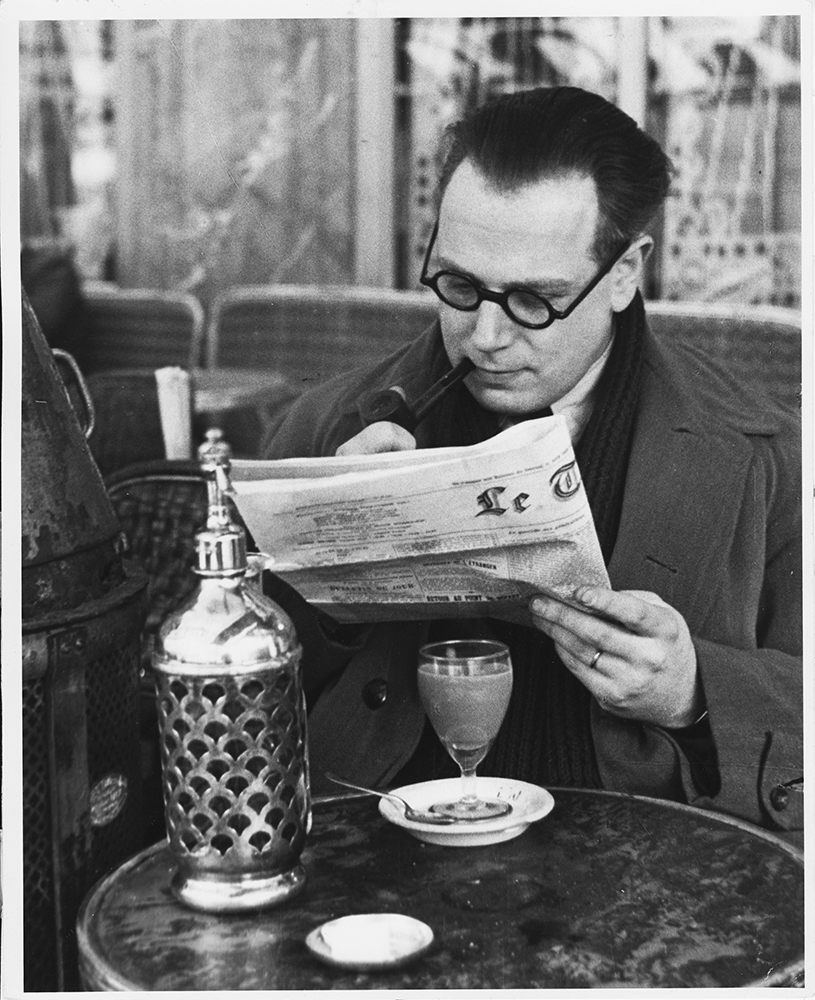

Wolf Franck in the Café du Dôme, Paris, around 1935. Frankfurt am Main, Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, EB autograph 1036 © Stanfordville, NY, Fred Stein Archive

Some of these authors were also active in the writers’ Schutzverband. Such was the case with the journalist Wolf Franck, whom Stein photographed in 1935 – reading a newspaper and smoking his pipe – in the famous Café du Dôme, the regular gathering place of many artists and intellectuals. In the Café du Dôme, a thorn in the side of the French police as the “meeting place of the leftist extremists”,[vi] Stein also took the only picture showing the famous photographer couple Robert Capa and Gerda Taro together. For a while Gerda Taro had rented a room from Stein and his wife Lilo, who had moved from Montmartre into a larger flat in the Rue Abel-Ferry in the 16th arrondissement. Stein’s photo of his lodger at the typewriter appeared in the communist journal “Regards” in 1938.[vii] The photograph was published on the occasion of the first anniversary of the death of the young photographer, who had been crushed by a tank during the Spanish Civil War.

Gerda Taro, Paris, 1936 © Stanfordville, NY, Fred Stein Archive

In 1934, Stein photographed the poet and writer Rudolf Leonhard, who “had a determining influence on the activities of the political-literary exile scene in France for over a decade, indeed […] he virtually [embodied] it in both its diversity and its failure”.[viii] Stein photographed Leonhard in a garret wearing a mottled grey woollen sweater vest. Perhaps the sweater suggests the lack of heating in the attic rooms that many cash-strapped emigrants had to rent – the poor insulation and countless stairs were the drawback of the cheap flats.

Rudolf Leonhard, Paris, around 1934, Frankfurt am Main, Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, EB autograph 1078 © Stanfordville, NY, Fred Stein Archive

Alfred Kantorowicz, who, with Rudolf Leonhard and David Luschnat, was in charge of the unsalaried organisational work of the Schutzverband,[ix] also lived in such a garret. In 1935 Stein very likely photographed him the “tiny attic room in Hotel Helvetia”,[x] which Kantorowicz shared with his partner. Daylight falls into the room – “2.40 x 3.50 metres square”[xi] – from the left, where sessions with friends and members of the German writers’ association were held, as Kantorowicz related in his autobiographical article “Alltag in der Emigration” (Everyday life in exile).[xii] In a photo that Fred Stein evidently found particularly successful – he toned the print in a warm brown – Kantorowicz, who was also head of the German Freedom Library, which aimed to collect all the works that had been “forbidden, burned, censored or hushed up” in Germany,[xiii] sits in front of a mirror with his back to the camera. Here, too, the thoughtful expression on the face of the emigrant dressed in a collarless leather jacket is memorable.

Alfred Kantorowicz, Paris, 1935 © Stanfordville, NY, Fred Stein Archive

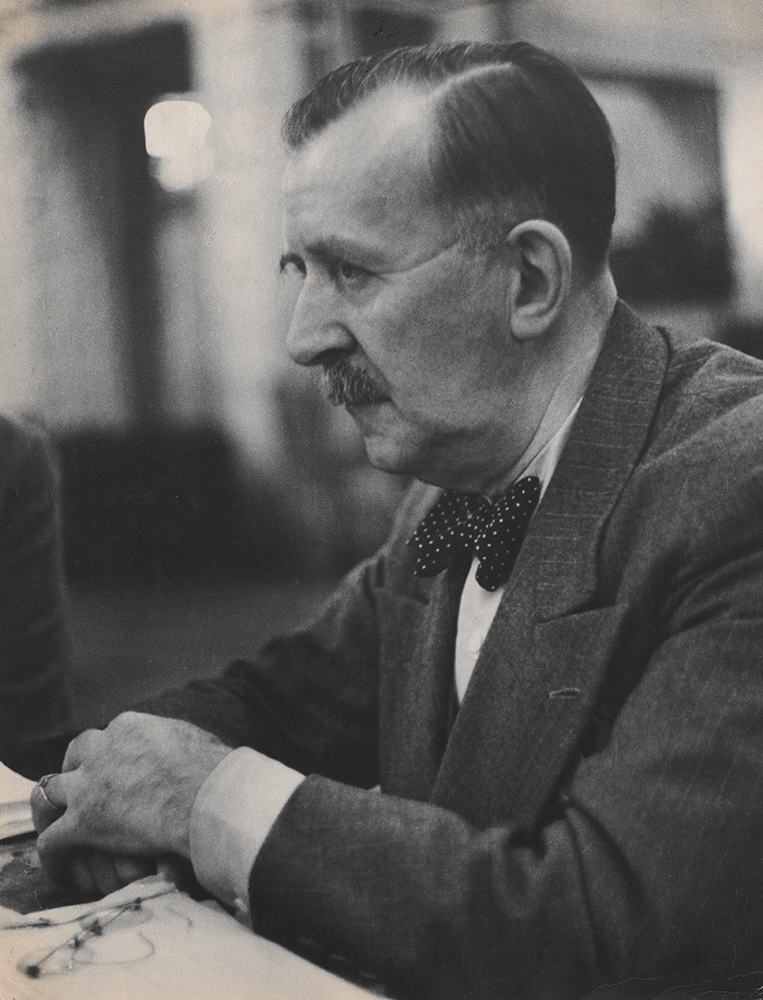

Heinrich Mann, the honorary chairman of the Schutzverband deutscher Schriftsteller and president of the German Freedom Library, lived in Nice from 1933 to 1940. On a visit to Paris, he resided in the stately Hotel Lutetia in the quartier Saint-Germain-des-Près, the gathering place of the international elite. “You can reach me by letter or telegraph until the 25th in Paris (7.) Hotel Lutetia, Bd. Raspail”, he informed his brother Thomas Mann in November 1935.[xiv] Since September of that year, the so-called Lutetia Circle had been meeting there, a group of communists, social democrats, representatives of other socialist groups, so-called Catholics and Bourgeois, predominantly writers who shared an anti-fascist position. In February 1936, a committee met in the hotel to prepare the founding of a German popular front. After the front’s founding conference in 1936 – as was written on the back of the photographs – Stein photographed the chairman of the Lutetia Comité, Heinrich Mann, as well as Ernst Toller, who also fought tirelessly against National Socialism. These portraits, taken by Fred Stein, are among the extremely rare photographic documents of the German movement for a popular front, which failed in the end due to the ideological differences of the various exile groups.

Heinrich Mann after the meeting in Hotel Lutetia in Paris to establish a German popular front, 1936 © Stanfordville, NY, Fred Stein Archive, Photo: Herling/Herling/Werner, Sprengel Museum Hannover

Sources

[i] Letter from Fred Stein to Dr Otto Croy, 25 June 1954 (Fred Stein Archive, Stanfordville, NY).

[ii] Questionnaire from the application to be recognized as a refugee, “Conditions of emigration”, 30 December 1936, Archives de la Préfecture de Police de Paris. Stein, active from a young age in socialist youth organisations, had been a member of the Socialist Workers’ Party SAP since 1931.

[iii] By April 1945, the newspaper Preussischer Staatsanzeiger had published 358 further lists of people to be expatriated, with a total of 39,006 names.

[iv] Letter from Fred Stein to Dr Werner Berthold, director of the German Exile Archive Frankfurt, 10 August 1965, Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt a. M.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Anne-Marie Corbin: Die Bedeutung der Pariser Cafés für die geflohenen deutschsprachigen Literaten. In: Fluchtziel Paris. Die deutschsprachige Emigration 1933-1940, Anne Saint Sauveur-Henn (ed.), Berlin 2002, p. 93.

[vii] Regards, vol. 7, no. 236 from 21 July 1938.

[viii] https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/gnd118727559.html#ndbcontent, retrieved on 1 March 2021.

[ix] Alfred Kantorowicz: Politik und Literatur im Exil. Deutschsprachige Schriftsteller im Kampf gegen den Nationalsozialismus, Christians, Hamburg 1978, p. 163.

[x] Ibid., p. 300.

[xi] Alfred Kantorowicz: Alltag in der Emigration. In: A. Kantorowicz: In unserem Lager ist Deutschland. Reden und Aufsätze. Paris, Éditions du Phénix, 1936. Reprinted in: Report from Exile – Fotografien von Fred Stein, ed. by Raphael Gross and Ulrike Kuschel for the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin 2020, p. 94.

[xii] Ibid., p. 96.

[xiii] A. Kantorowicz: Politik und Literatur im Exil, p. 257.

[xiv] Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann: Briefwechsel 1900-1949, Frankfurt am Main 1984, p. 225.