Fan with the Slogan “Je désire voter”

Paulina Szoltysik | 2 November 2022

Equal voting rights for women were hardly imaginable at the start of the 20th century. What could a fan have had to do with French women’s fight for enfranchisement? Research assistant Paulina Szoltysik explains everything in this blog post for the exhibition “Citizenships: France, Poland, Germany since 1789”.

“Ce qu’il faut aux femmes pour s’affranchir de la tyrannie masculine – fait loi, – c’est la possession de leur part de souveraineté; c’est le titre de Citoyenne française, c’est le bulletin de vote.”1 Hubertine Auclert

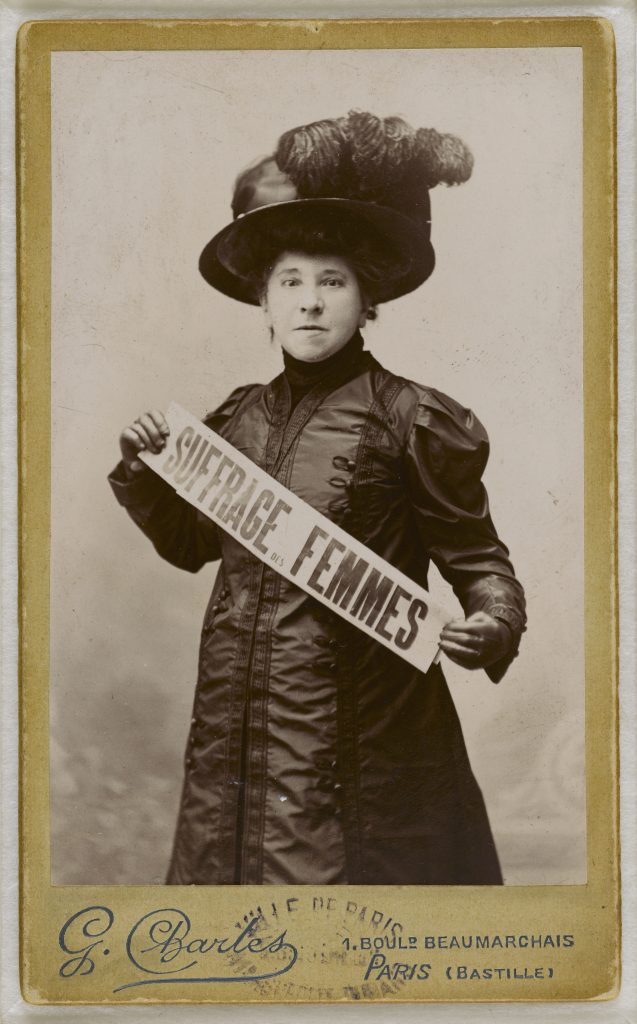

These are the words of Hubertine Auclert, the first French woman to call herself a feminist, who demanded that women should have the right to vote as early as the mid-1870s. Only by going to the ballot box, she argued, would women become responsible citizens. In 1880 she scandalized the nation: she demanded to be registered as a voter, and when her demand was rejected, she refused to pay her taxes. Her argument? No rights meant no responsibilities! Almost 35 years and many demonstrations, petitions, and articles later, female suffrage had still not been introduced in France. Despite growing support, the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate continued to reject it.

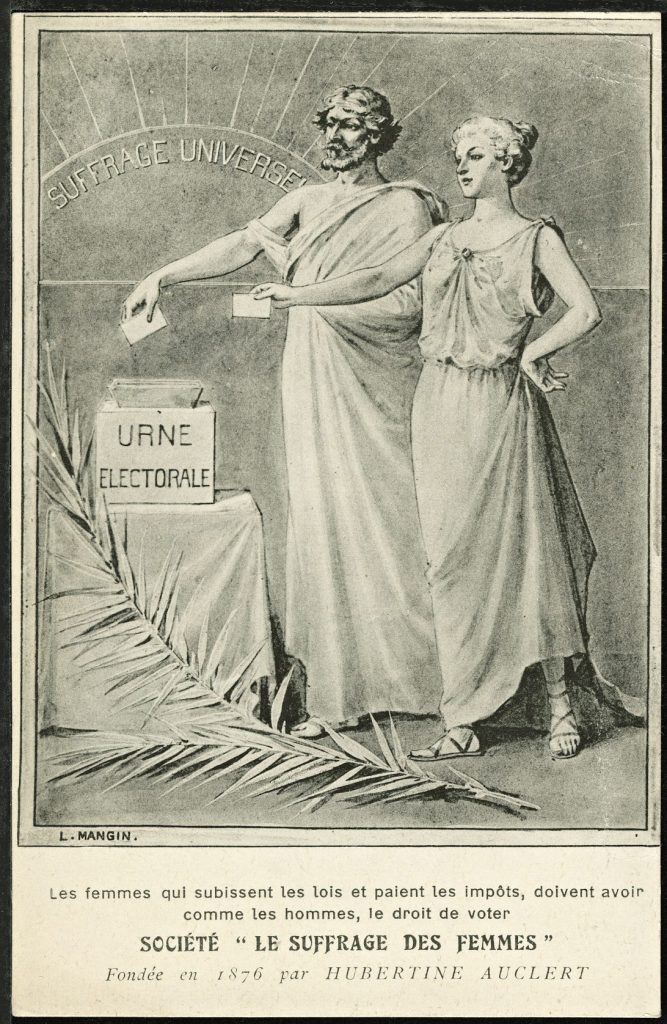

Auclert founded the association in 1876 as Le droit des femmes; the name was changed in 1883 to Le Suffrage des femmes, Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand

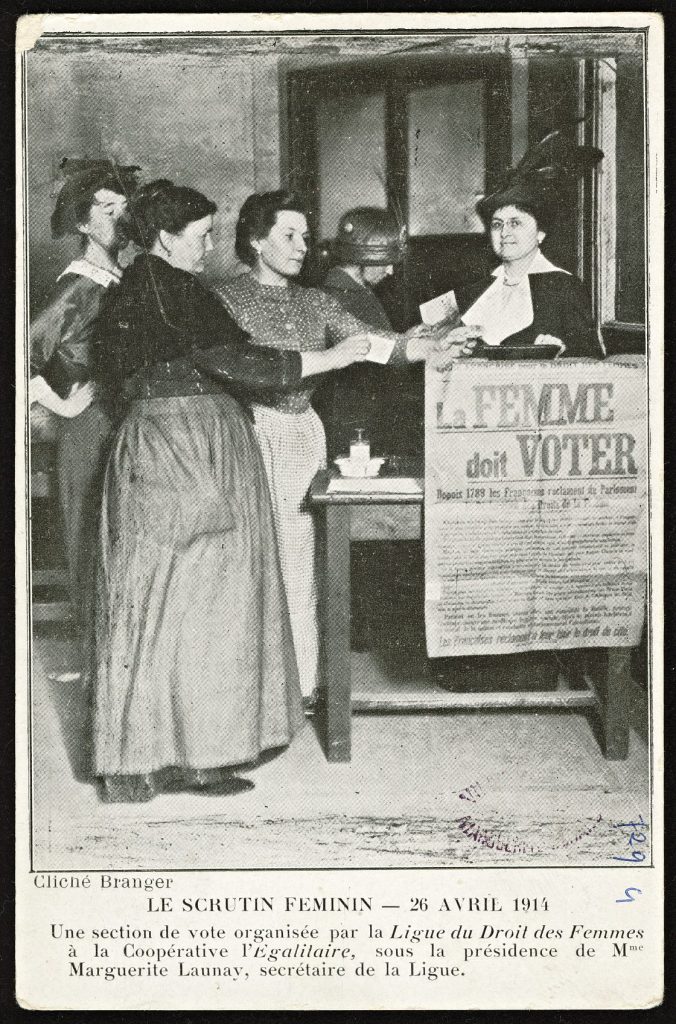

Photograph of a temporary polling station printed on a postcard, Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand

Fan proclaiming “Je désire voter”, celebrating the symbolic referendum in Paris, 1914, Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand

Hubertine Auclert, Frankreich, c. 1880/90, Photo: G. Charles, Paris, Bibliothèque Marguerite-Durand

The campaigners for women’s suffrage and their supporters were not short of creative ideas for drawing attention to their struggle, however. In his editorial of 9th March 1914, Gustave Téry, editor of the newspaper “Le Journal”, called on all French women to go to the ballot box. He and his paper organized a symbolic referendum, distributing ballot papers that invited participants to vote on the question “Mesdames, Mesdemoiselles, désirez-vous voter un jour?” The campaign received wide support, with many women’s associations and private individuals joining the cause and organizing temporary polling stations. These included the association founded by Hubertine Auclert Le Suffrage des femmes (Women’s Suffrage) and other groups that supported votes for women, including La Ligue du droit des femmes (The League for Women’s Rights), La Ligue nationale pour le vote des femmes (The National League for Women’s Suffrage) and L’Union francaise du suffrage des femmes (French Union of Women’s Suffrage).

Voting opened on 26th April 1914, the same day that elections to the French Chamber of Deputies were being held. Ballot papers were accepted up to 3rd May 1914 at the improvised polling stations and could also be handed in at any outlet selling Le Journal all over France.

In total, 505,972 French women voted in favour of the proposition, placing their cross next to the response “Je désire voter”. Only 144 voted against. To publicize the unequivocal result of the referendum, postcards were printed bearing photographs of the temporary polling stations and a statement of the resulting vote count. A particularly beautiful, and at the same time practical means of advertising the cause was a paper fan bearing, in large letters, the slogan “Je désire voter”. It’s green and white colours echoed those often seen at demonstrations by British suffragettes. On 5th July 1914, the fans were distributed to participants in one of the largest street demonstrations ever held in Paris, along with primroses and olive branches. Between 5,000 and 6,000 people marched from the Jardin des Tuileries along the Seine to the statue of Nicolas de Condorcet, the Enlightenment philosopher who had spoken out as early as 1790 in favour of equal citizenship for women.

The outbreak of the First World War in July 1914 put an abrupt end to the momentum of the women’s movement. The international crisis prompted many activists to put their demands for equal rights on hold.

Women’s desire to take part in politics survived the war, however, as proven by the vote on female suffrage that took place in the Chamber of Deputies in 1919. The majority of deputies voted in favour. The Senate, however, blocked the bill, and so prevented any change in the law. It was not until 21st April 1944 – 26 years later than in Germany and Poland – that women in France received the right to vote and stand in elections.

[1] What women need in order to free themselves from the tyranny of men is to have their share of sovereignty, the title “French citizen”, the vote.

Literature

Auclert, Hubertine: La Citoyenne, in: La Citoyenne. Journal Hebdomadaire, 13.2.1881.

Bard, Christine: Histoire des Femmes dans la France des XIXe et XXe siècles, Paris 2013.

Bock, Gisela: Frauen in der europäischen Geschichte. Vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, 1. durchges. Aufl., München 2005.

Condorcet: On the emancipation of women. On giving women the right of citizenship (1790), in: Steven Lukes/ Nadia Urbinati (Hrsg.): Cordorcet. Political Writings, Cambridge 2012 , S. 156-162.

Hause, Steven C.: Hubertine Auclert. The French Suffraguette, New Haven/London 1987.

Kedward, Rod: La Vie en Bleu. France and the French since 1900, London 2006.

McMillan, James F.: France and Women 1789 – 1914. Gender, Society and Politics, London/New York 2000.

Metz, Annie: Éventail suffragiste, 1914, in: Histoire par l’image (März 2017). URL : histoire-image.org/etudes/eventail-suffragiste-1914 (16.6.2022).

Ou les femmes pourront voter dimanche à Paris, in: Le Journal, 25.4.1914.

Sumpf, Alexandre, Le vote des femmes en France : le „référendum“ du 26 avril 1914, in: Histoire par l’image (März 2017). URL: histoire-image.org/etudes/vote-femmes-france-referendum-26-avril-1914 (23.6.2022). Téry, Gustave: Aux Urnes, Citoyennes! Le “Journal“ organize une experience decisive, in: Le Journal, 9.3.1914.

|

Foto: Privat |

Paulina SzoltysikPaulina Szoltysik worked as a research assistant on the exhibition “Citizenships: France, Poland, Germany since 1789” at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. She studied contemporary history at the University of Potsdam and the Nikolaus Kopernikus University in Toruń. |