Embroidery as a Medium for the Representation and Ordering of the World

Julia Franke | 15 November 2023

A glance at the collections of the Deutsches Historisches Museum reveals the immense variety of objects that are related to different epochs and topics of German history. They tell stories of our past or current lives, of famous or often unknown persons and events. In our new blog series #Umweltsammeln (#Environmentcollecting) we present various objects that have to do with the topic of “environment”. Unexpected questions raised by the heads of the different collection sections open new perspectives on historical objects and often reveal startling parallels to questions that deal with our current world.

Julia Franke, head of the DHM collection that includes civil textiles, takes a look at an embroidery picture that depicts nature according to the Enlightenment’s principles of order – thereby combining delicate flower garlands with a volcanic eruption.

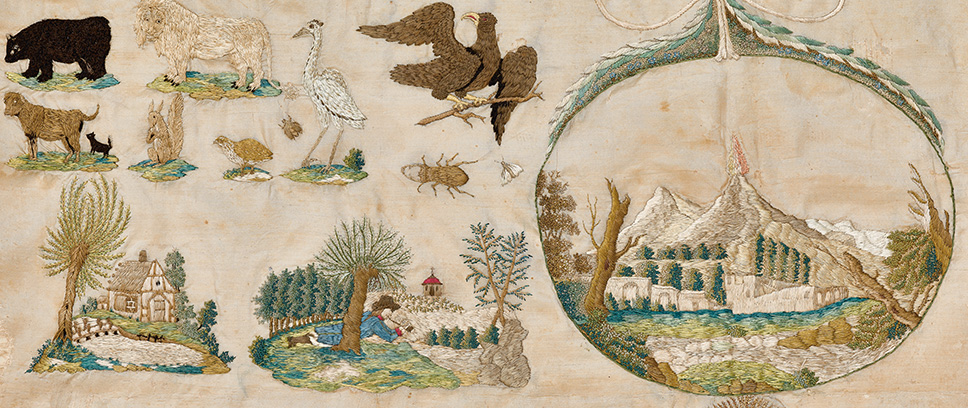

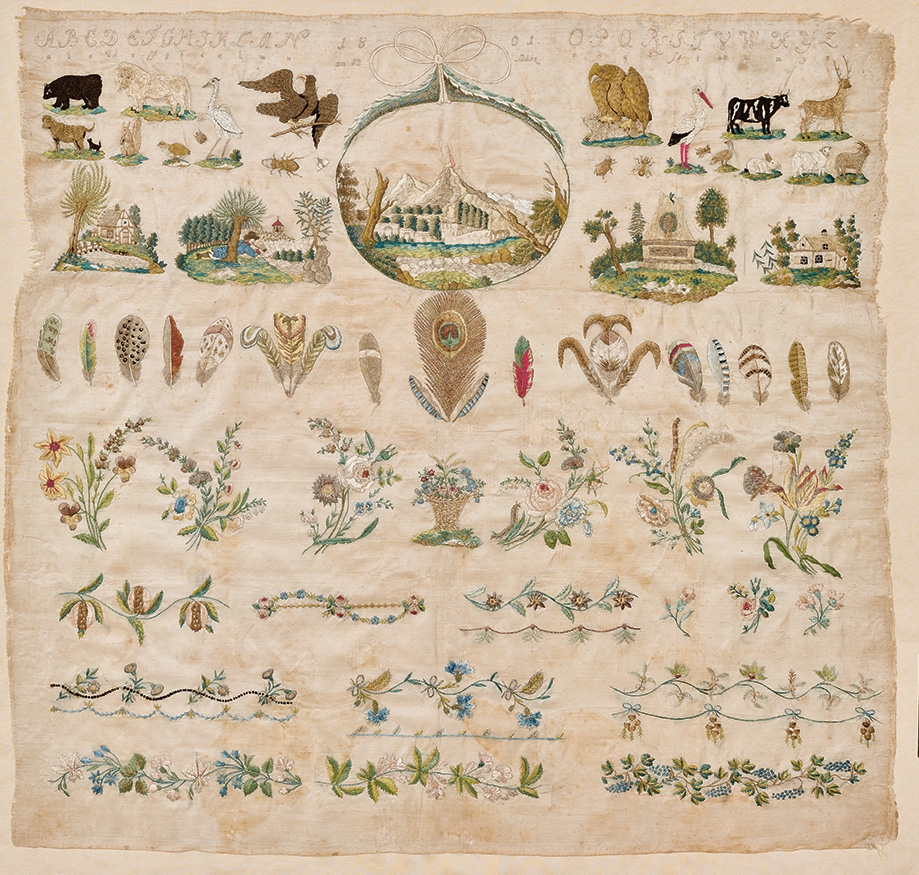

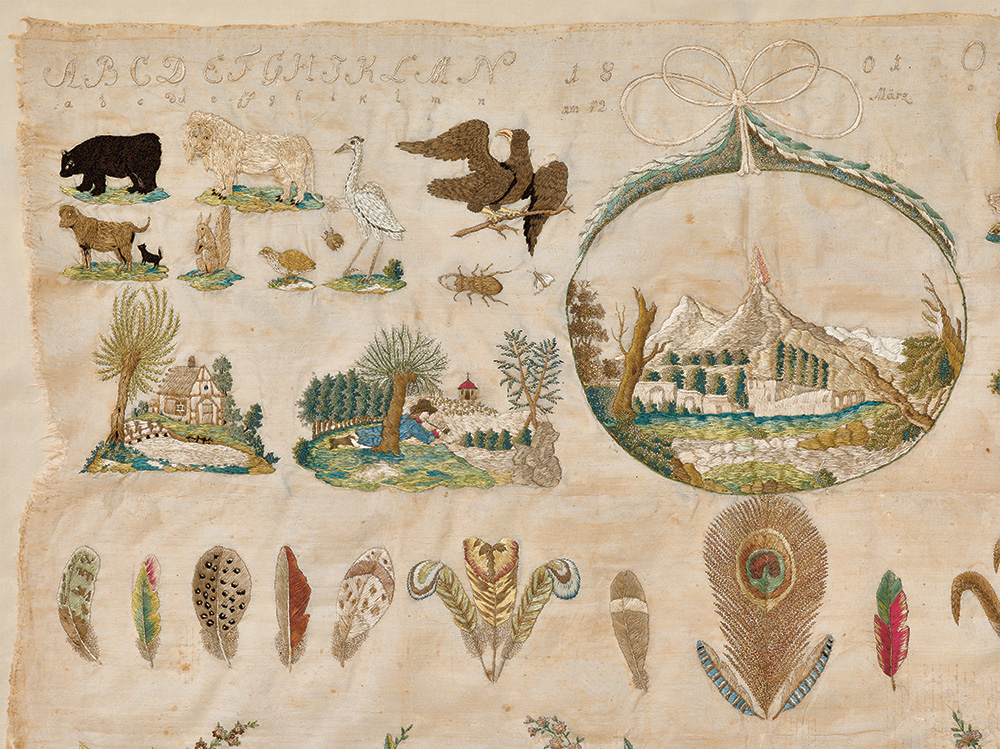

At first glance, the embroidery picture appears graceful and gay with its miniature animals and colourful flowers and feathers, and yet an ordering, perhaps even systematising hand has set bounds to the multifarious manifestations of nature depicted there. The embroidery presents a mostly domestic variety of flora and fauna in a naturalistic and appreciative manner. Beneath a row of embroidered letters of the alphabet and the probable date of origin of the embroidery (12 March 1801) are groups of animals of different species – mammals, birds, insects – and various scenes of typical, idyllic landscaped gardens. The centrally positioned motif, adorned with a delicate ribbon, is the depiction of a smoking volcano, probably Vesuvius. Thus, an ominous natural phenomenon such as a volcano eruption finds a place in the iconography of the embroidery. This is followed by a row of around 20 pictures of feathers. The lower half of the embroidery consists of depictions of plants – floral motifs in the form of bouquets and garlands. The bouquet on the right is even “visited” by caterpillars or a butterfly.

Representative needle painting

These ornate needlework designs were created in the 19th century to embellish interior decoration as well as clothing and accessories. The elaborate adornments were meant to give additional representative value to the respective objects. Embroidered on silk, the picture is distinguished by the subtle nuances of colour that took hold in the 18th century. The satin stitch pattern gives the colour gradients or shading of the yarn a softer touch. The depictions of the feathers and plants in particular help to explain why this needlework technique is also called needle painting.

These embroideries were made not only in commercial workshops and cloisters, but also in private households. In bourgeois and aristocratic circles, silk embroidery in particular was considered an acceptable pursuit for women and girls. As a rule, the individual motifs and patterns were handed down to the next generations through traditional cloths. But in Germany, so-called pattern books had been in existence since the 16th century. They included patterns in the form of woodcuts. In the 18th century, regular pattern books containing copperplate engravings came onto the market, providing the embroiderers with inspiration for decorations of cloths and covers, aprons, bordering of dresses, and bonnets.[i] In the late 18th and especially in the 19th century, such embroidery pictures were often framed and hung on the wall.

Knowledge of natural history

The topic and contents of this embroidery are not based on Christian iconography, which was often found in the context of such pictures with embroidery patterns. Instead, this precise and carefully designed embroidery points in its nearly zoological perfection to a knowledge of nature and a desire to be able to recreate it in all its details. Among the depictions of animals are birds, such as golden and white-tailed sea eagles, herons, black grouse and storks, as well as bears, cows, stags, dogs, cats, squirrels, sheep and goats, but also insects, such as maybugs and stag beetles, cabbage butterflies and ants. Underlying the choice of the different motifs are intellectual and historical principles of the 18th century as axioms of the Enlightenment: Methodological procedures founded on rationality, empirical evidence and universalism are linked together with an ordering of the world.

Ordering of the world is a fundamental practice of scientists: living beings are differentiated according to certain traits, forming kinds, species, classes, and other categories. Written by Carl Linnaeus, Europe’s leading classifier of plants, the book Species Plantarum, already published in 1753, was still the standard work at the beginning of the 19th century for the nomenclature of plants. This concept of classification is also found in our silk embroidery picture. The arrangement of the motifs follows a systematisation that yields a differentiation of animals, plants, and human ideas and influences. Knowledge of “Nature” is and was rendered here – on the basis of the cultural technique of embroidering.

A picture of nature

On the one hand, the unknown embroiderer of this picture presented here an empirical and, indeed, meticulous work about “Nature” and thus stood in the tradition of the Enlightenment. At the same time, the selection of the motifs – especially those in the four scenes that were inspired by landscaped gardens or cultivated pastoral landscapes – follows the cult of sensitivity of the Romantic Era. The animals and plants, floral garlands and idyllic scenes, were appreciated directly due to their aesthetic and symbolic qualities. Among the embroidered flowers are, for instance, violets and roses, symbols of modesty, humility, or love. The forms, colours and delicacy of their blossoms were to be enjoyed as truthful and beautiful. The landscaped garden scenes also comprised a political dimension: as opposed to the strictly geometrically structured gardens of the Baroque, they were freer, supposedly “more natural” depictions of nature – seen as an expression of a more liberal and harmonious social order. Nature here is still divided into structured classifications, but at the same time it is meant to evolve in a less restricted way than in earlier times. The aesthetic enjoyment of natural history motifs was thus combined with feelings of romance and freedom.

The depiction of the volcano eruption only seemingly sets itself apart from the other motifs. For in the course of the 19th century, a change in the understanding of natural disasters came about. As new research was undertaken, the destructive forces of nature could be more closely examined and their origin better understood. From this time on, the forces were no longer interpreted as reactions of an angry God and they therefore became less frightening.[ii] Now even beauty and grandeur could be divined in this force and violence – and in this way a volcano eruption became a motif in an embroidery. The aspiration of the time to study and understand “Nature” is combined in this object with an aesthetic representation and communication of nature and naturalness. Nature as a cherished value of the Enlightenment and the emerging bourgeois society could thus be found hanging on the wall – embroidered on silk.

[i] Cf. Nina Gockerell: Gestrickt, gestickt, gedruckt. Mustertücher aus vier Jahrhunderten. Weilheim 1978.

[ii] Cf. Christoph Daniel Weber: Vom Gottesgericht zur verhängnisvollen Natur. Darstellung und Bewältigung von Naturkatastrophen im 18. Jahrhundert. Hamburg 2015.

|

|

Julia FrankeJulia Franke is a historian and head of the collection for everyday culture that includes civil textiles in the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |