Only on 8 May? Days of Liberation in Europe

Martin Borkowski-Saruhan | 7 May 2025

Ever since Richard von Weizsäcker’s famous speech in 1985, 8 May is usually celebrated as the Day of Liberation. What was liberated – over a much longer period that began in 1943 and did not end on 8 May 1945 – were the European countries occupied by Germany, the first concentration and extermination camps, and the victims of the Nazi regime. Images of the liberation emerged in Europe’s cities that provide insight into the contradictions inherent in the end of the war. A miniseries.

Part 1: Warsaw

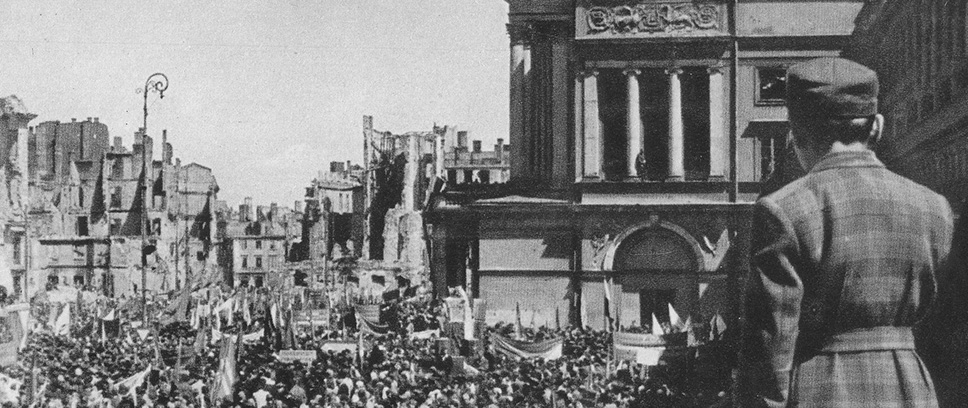

To claim that 8 May 1945 had played no role at all in Warsaw would be an exaggeration. For the end of the war in Europe was of course also celebrated in the capital of the country which was the first to be invaded by Germany. Photographs record the masses of people gathered at plac Teatralny (Theatre Square) on the day after the unconditional surrender of Germany, holding banners high in the sky and waving flags. Also seen there is a delegation of the Biuro Odbudowy Stolicy (BOS, Office for the Reconstruction of the Capital), with whose participation only a few days earlier, on 3 May 1945, the city’s first postwar exhibition had been opened in the National Museum in Warsaw under the telling title Warszawa oskarża (Warsaw Accuses). To set the date of the exhibition opening on 3 May, the national holiday of the constitution of 1791, and thus to stress the historical significance of Polish culture and statehood, fit into the strategy of the show, which was to illustrate the years of barbaric German rule over Poland by means of displaying, of all things, the remnants of the Polish cultural goods that the Germans had destroyed. Broken artworks, fragments of blown-up statues and remains of the extensive theft of art were piled up together in a grotesque aesthetic assemblage.[1] It blurred the boundary between inside and outside. The unmistakably visible history of violence wrought upon the city was carried over into the hastily arranged rooms in the heavily damaged museum. The last room arranged by the BOS opened a view to the future. The possibility of a reconstruction of the city, which many people had doubted at first, was not only emphatically affirmed, but also backed up by entirely tangible visions.

In face of the bleakness of the present, such strong visions were needed. This conclusion is underscored in the memoirs of Lech Tulicki, who experienced the happenings as a 15-year-old youth: “I stood at Theatre Square, because we were called to go there […] There was a rally […] and on the balcony of the Opera House […] were all these bonzes, and many thousands of people stood below. Nobody wanted to go there willingly, but people were picked up at the workplaces and fetched from the schools. Was that a rally of joy? No. […] It wasn’t so, nobody danced at Theatre Square. The people were shabby, tattered, and were earning starvation wages.”[2]

Material hardship, hunger, ruins, coercion, lack of freedom – this is what Tulicki pinpoints as central aspects of what “liberation” by the Red Army brought for many people in Warsaw. Precisely because the Germans had overlaid the country for years with unprecedented terror and created the scene of the Holocaust and other mass crimes, the expectations placed on the end of the occupation and the regaining of freedom and independence were all the greater. For the Jewish population of the city – before the war the second largest Jewish community in the world – the liberation, with very few exceptions, came too late. The systematic mass murder in the Treblinka extermination camp from 1942 on was followed by the crushing of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and its obliteration in May 1943.

Shortly before the end of July 1944, the Red Army stood before the suburbs of Warsaw, where the Germans had brought them to a halt. But instead of carrying on the offensive and supporting the Warsaw Uprising, which began on 1 August 1944 under the leadership of the Armia Krajowa (AK, Home Army), the Soviets did nothing for a month. In September 1944, after heavy fighting, they finally occupied the right bank of the Vistula with the Warsaw municipal district of Praga – and once again went into waiting. This allowed the Germans to crush the uprising with brutal force, to raze the rest of the city in retribution, and to deport the remaining survivors to camps. The demolition and conflagration of buildings was preceded by an organised plundering of gigantic magnitude.

Immediately after taking over Praga, the Soviet authorities began installing a terror apparatus. In September 1944, the Stalinist secret service NKWD set itself up in a tenement in Strzelecka Street, which included a prison and an execution site.

When on 17 January 1945, after brief skirmishes with the retreating German army, the troops of the 1st Army of the Polish Military and the 1st Belorussian Front of the Red Army finally advanced into the Warsaw’s left bank, they found the city centre almost deserted. Amidst the rubble, the few remaining citizens of Warsaw emerged from the ruins, where they had hidden for several months. Despite the inglorious failure to attack, the Soviet-led troops celebrated their putative victory on 19 January 1945 with a parade and thus created an important topos for the official communist view of history, which held until 1989. NKWD units subsequently expanded their terror apparatus into the centre of Warsaw.

Despite the destruction and disastrous living conditions, more and more Warsaw citizens returned to the city and found provisional solutions for the reorganisation of the city. It is estimated that in the second half of January 1945, there were already 12,000, later in the year 20,000, and finally in 1946 290,000 people living on the left bank of the Vistula.[3]

[1] See the complete list of objects in the exhibition in: Kazcmarczyk, Dariusz: Pamiętnik wystawy „Warszawa oskarża”: 3 maja 1945 – 28 stycznia 1946 w Muzeum Narodowym w Warszawie. In: Rocznik Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie 20 (1976), pp. 599–642.

[2] Interview with Lech Tulicki (2012). In: Archiwum Historii Mówionej Domu Spotkań z Historią i Ośrodka KARTA, Sign. AHM_2714.

[3] Przywara, Adam: Nachleben oder Wiedergeburt? Warschau in den 1940er Jahren. In: Raphael Gross, Agata Pietrasik (Hg.): Gewalt ausstellen: Erste Ausstellungen zur NS-Besatzung in Europa, 1945–1948, Berlin 2025, p. 125.

|

|

Martin Borkowski-SaruhanMartin Borkowski-Saruhan is scientific curator for Eastern Europe at the documentation centre “German Occupation of Europe in the Second World War” (ZWBE) at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |