Only on 8 May? Days of liberation in Europe

Axel Bangert | 25 June 2025

Since Richard von Weizsäcker’s famous speech in 1985, the 8th of May is primarily celebrated in Germany as the day of liberation. What was liberated, however – over a much longer period that began in 1943 and did not end on 8 May 1945 – were the European countries occupied by Germany, the first concentration and extermination camps, and the victims of the Nazi regime. In European cities, images of the liberation emerged which provide insight into the contradictions of the end of the war. A miniseries.

Part III: Paris

On 7 May 1945, the unconditional surrender of Germany was signed in Reims, the headquarters of the Western Allies in France. It came into effect at 11:01 pm on the following day. Since 1981, the 8th of May has been a national holiday in France commemorating the end of the Second World War in Europe. But what marked the end of the war to an even greater degree in the remembrance of the French people was another event: the liberation of Paris on 25 August 1944 and the triumphal procession through the city on the following day. Amidst the cheers and jubilation of tens of thousands of Parisians marched General de Gaulle, head of the Free French Forces and the Provisional Government of the French Republic, along the Champs-Élysées, accompanied by members of the Résistance. De Gaulle laid a wreath beneath the Arc de Triomphe at the grave of the Unknown Soldier – a ritual that has since been carried out by French heads of state every year on 8 Mai. It was a highly symbolical staging that solidified not only de Gaulle’s claim to leadership, but also the myth of the Résistance.

The fact that the liberation of Paris had such a radiant effect had not least of all to do with the images that were soon shown round the world: street skirmishes of the Résistance with the German occupiers, the advance into the city by the French 2nd division under General Leclerc side by side with the American troops, and pictures of the inhabitants joyfully greeting their liberators – all this was recorded in numerous photographs and films. French civilians and members of the Résistance, allied military photographers and various war correspondents – including such prominent names as Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Ralph Morse and Lee Miller – created pictures that were disseminated far beyond France and became icons of the end of the war.

In the meantime, pictures of the liberation of Paris have been increasingly called into question as to whether they might have inflated the importance of the historical events or recorded them incompletely. This applies above all to the narratives that made such a strong, long-lasting contribution to the heroisation of the liberation and the remembrance of the Second Worl War in postwar France.

What has been queried most of all is the idea of an autonomous French liberation from the German occupation, which de Gaulle formulated in the famous speech he delivered at City Hall, Paris, on 25 August 1944: “Paris! […] Liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies, with the support and the help of all France […]!” But, in fact, the liberation of Paris came about largely through the support of the Western Allies, who had originally planned to bypass Paris in order to advance to the German border as quickly as possible. After a general strike and an armed revolt had been launched in Paris, de Gaulle convinced Eisenhower to take Paris first and to let French troops march in at the head of the procession. Against this backdrop, the pictures of the parade on the Champs-Élysées appear to be an expression of de Gaulle’s political calculation to stage France as the victorious power.

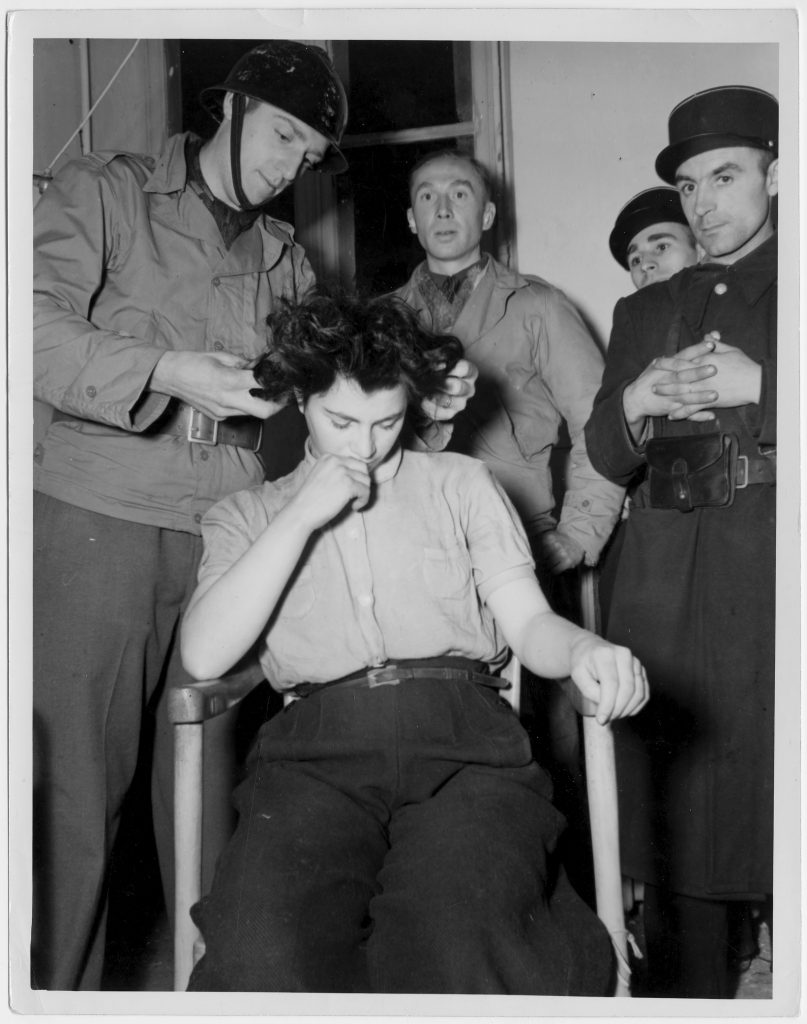

The pictures of the liberation of Paris also contributed to establishing the central role of the Résistance in the postwar French view of history. Almost indiscernible in this view was the fact that the country had not only liberated itself from the German occupation, but also from its own collaborative regime. In liberated parts of the country, spontaneous acts of revenge against collaborators erupted in 1944/45, the so-called “épuration sauvage” (“wild purge”). Women accused of so-called “horizontal collaboration” – intimate relations with German occupiers – were often publicly humiliated by having their hair shaved off and being exposed in the streets to the rage of the population. Pictures of such actions stand in sharp contrast to the celebration of national unity in the images of the liberation of Paris. The wave of anger was quickly followed by a swell of forgetting and repression. The controversy about collaboration then focused on the leaders of the Vichy regime; many of the people who had been interned for suspected collaboration were freed after the war. The amnesty law of 1953 showed that France now had to devote itself to reconstruction.

While the people in Paris celebrated, violence and war long continued in other parts of the country. On the same day the capital was liberated, German soldiers murdered 124 civilians in the town of Maillé near Tours. Before the Germans finally capitulated in Reims, the battles in Metz, in the Vosges and in Alsace claimed the lives of tens of thousands of allied and German soldiers. Thousands more French soldiers were killed in the battles of Colmar at the beginning of 1945. It was only after 8 May 1945 that the German submarine bases at La Rochelle and Saint-Nazaire on the Atlantic coast surrendered.

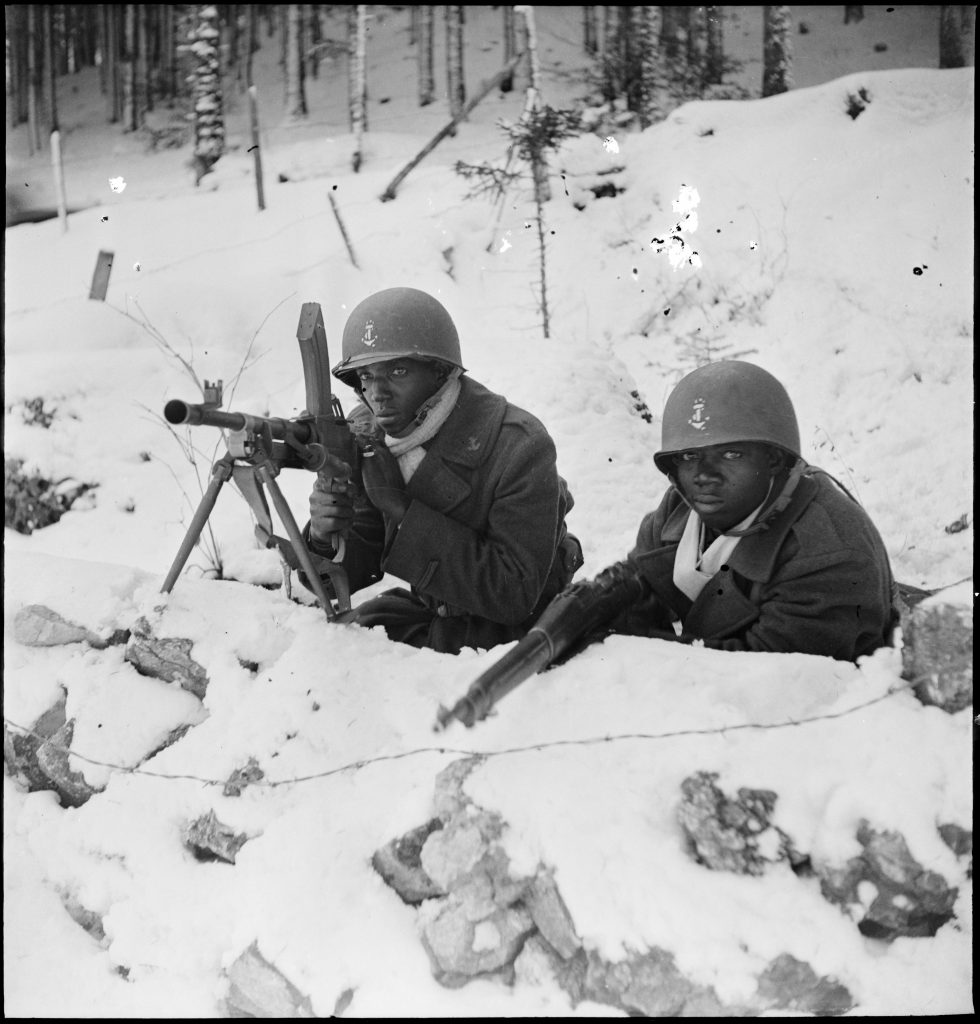

As in the First World War, many colonial soldiers from West, Central and North Africa fought for France in the war. They even formed the majority in some units of the Free French Forces. After the allied and French troops landed in southern France in autumn 1944, the so-called “blanchiment” (“whitening”) began: some 20,000 African soldiers were removed from the front divisions and replaced by resistance fighters of the French Forces of the Interior and French volunteers. Eisenhower first accepted de Gaulle’s call to allow French soldiers to march at the liberation of Paris if the troops would consist only of white soldiers. This is why there are hardly any Black colonial soldiers to be seen in the pictures of the parade, although they made an important contribution to the recapture of France.

The stylisation of France as the victorious power, the concentration on the Résistance instead of the painful chapter of the collaboration, the suppression of the merit and sacrifice of the colonial soldiers – all this shows that the pictures of the liberation of Paris highlight, on the one hand, but also hide key aspects of the end of the war in France. There was apparently no room in the heroic narrative of the self-liberation from German occupation for the fact that the end of the Second World War brought with it the destabilisation of the French colonial empire. Soon after the capitulation of Japan on 2 September 1945 had brought the Second World War to a final conclusion, France became emerged in a new phase of military conflict – this time in a struggle to maintain its colonial empire, particularly in Indochina and Algeria.

|

|

Axel BangertDr. Axel Bangert is research curator for Western Europe in the Documentation Centre “German Occupation of Europe in the Second World War” (ZWBE) at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |