Argula von Grumbach – A Reformist Protest

Sophie Potente | 17 March 2021

“I send you not a woman’s ranting, but the Word of God as a member of the Church of Christ.”

It was Argula von Grumbach who wrote these words in 1523 at the end of a heated letter to the faculty of the University of Ingolstadt. Sophie Potente, research volunteer for the exhibition “From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere” explores in this DHM blog why a woman of the people raises her voice and challenges the professors to a discussion – and that in public. Virtually unthinkable in the year 1523.

Compared with most women of the 16th century, a great deal of documentation has come down to us about Argula von Grumbach. Pamphlets, letters and documents tell of the life she led around the years 1492 to 1557.

Born Baroness of the Empire Argula von Stauff, she was privileged to learn reading, writing and arithmetic. On her tenth birthday her father, Bernhardin von Stauff, gave her a Bible in German translation. A rare birthday gift, because the Catholic Church was suspicious of laypeople being allowed to read the Holy Scriptures. Since the Latin editions could only be read by scholars, the Church was thus assured of the prerogative of interpreting the Bible. Argula could not read Latin.

To own a German Bible cannot be seen as an act of rebellion. The family was devoutly religious. A prayer book that belonged to Argula reflects her piety: the importance of good works, the worship of the “Blessed Sacrament”, confession, and prayer for the salvation of deceased members were all part of her Christian life.

The Bible, her prayer book, and her deep faith accompanied her throughout her life, even through the loss of two husbands and three of her four children. But also through the turbulent years of the Reformation. Her faith, her Bible reading, and Martin Luther’s writings allowed her to understand herself as a good Christian without the control of the Catholic Church, from which she had turned away at an early age.

Medal with the portrait of Argula von Grumbach, Hans Schwarz, Nürnberg, around 1520 © Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg

This self-understanding is documented in eight printed pamphlets. Argula von Grumbach’s medial presence began in the year 1523. One of her letters appeared in print that year. It was reprinted 16 times within 12 months. Only the writings of the reformers Martin Luther and Andreas Bodenstein, known as Karlstadt, met with such resonance. The conditions under which the letter was written and its explosive nature account for its success.

The case of Arsacius Seehofer

While Martin Luther’s thoughts on the Reformation had been spreading like wildfire since 1517, the Bavarian dukes meanwhile undertook stringent measures to stop the reform activities and thus to secure their own existence. The power of the nobility and that of the Church were closely interlinked. They reinforced each other. In 1522 the nobles decreed the Bavarian Mandate on Religion, which introduced censorship and banned the books and pamphlets of Luther’s adherents as well as the spread and discussion of the Lutheran teachings. There were even spies in the taverns to monitor conversations.

Stronghold of the anti-Lutheran movement was Ingolstadt. Gabriel von Eyb, Prince-Bishop of Eichstätt and Chancellor of the University, was the first German bishop to have the papal bull of excommunication published against Luther. Johann Eck, Luther’s bitterest adversary who was substantially involved in formulating the bull, also taught there.

In 1522 the young Arsacius Seehofer returned from his studies in Wittenberg to this climate of censorship and persecution. Intoxicated with the new ideas and fervently supporting the cause of the reformers, he called Wittenberg the New Bethlehem where Christ was born a second time. He was soon denounced and arrested. Threatened with torture, he was forced to recant 17 teachings of the reformers and was supposed agree to be punished as heretic, but in the end was banned to Ettal Abbey.

Do not hold your tongue when others are silent

Argula von Grumbach had followed the situation in Ingolstadt and could no longer put up with it. The silence of the others made it impossible for her not to react. She sharply condemned the behaviour of the Ingolstadt theologians, saying that they were acting tyrannically against people with different ideas and confusing human and divine reason.

She was ready to dispute with them and to weigh her understanding of the Bible against the erudition of the theologians. They no doubt perceived the challenge of a woman and layperson to be particularly impertinent because she wanted to debate with them in German and not in Latin.

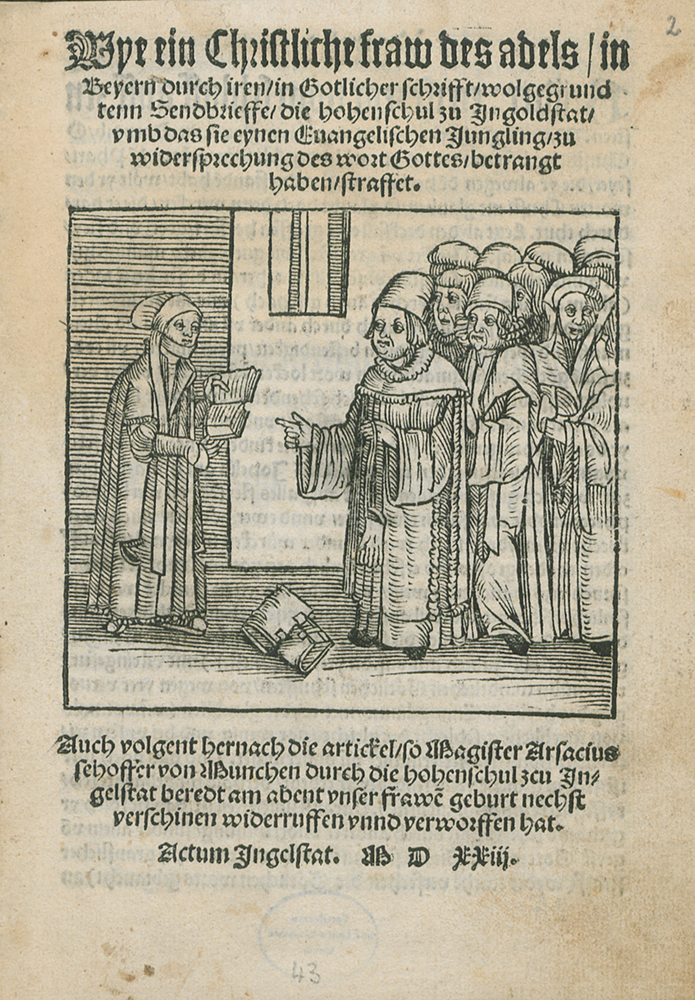

Like a Christian Woman, Argula von Grumbach, Erfurt, 1523 © Forschungsbibliothek Gotha der Universität Erfurt

The university declined to respond. But Argula’s letter was published as a pamphlet, and furnished with an unequivocal woodcut on the cover, which demonstrated approval from the other side. It was followed by seven other published letters of protest that Grumbach sent to dukes, scholars and clergymen. Around 30,000 copies of her writings were quickly circulated. Her success with the broad public cannot be explained merely by the reformist content. Argula von Grumbach wrote openly and easily understandable for all. Her theological argumentations in the language of the people created a bridge between her fellow laypeople and her concerns.

The sentence that has come down to us – “I send you not a woman’s ranting, but the Word of God as a member of the Church of Christ” – captures the core of Grumbach’s theological stance and medial effect: it encompasses the power of the reformed ideas and stands for a new self-consciousness of the faithful to raise their voice in reference to the Word of God. And its transmission in the form of a pamphlet speaks of a medial dissemination that creates publicity and generates excitement – thus capturing the spirit of the time.

An early feminist?

Argula’s engagement did not stop with her writings on the teachings of the Reformation. She also publicly criticized the rampant violence of men against women, their rudeness and perfidy, and took a stand for other women who suffered from abuse by their male relatives. It is not known whether she had to experience such behaviour herself. It is certain, however, that at the latest after Argula’s husband had been dismissed from his service under Catholic nobles due to her reformist activities the relationship between them was deeply shaken. Friedrich von Grumbach, an unwavering Catholic, was disgraced and humiliated: he was told he was unable to silence his wife and should have had her walled in.

While Argula von Grumbach has often been seen as an early feminist due to her support for other women and her vilification of male brutality, the Grumbach biographer and researcher Peter Matheson sees her actions and thoughts entirely as an outgrowth of her reformist convictions.

“For Argula it was not about her rights, but about the glory of God, the freedom of the Word,” writes Matheson.

“She saw the baptismal vows as authorization to resist evil publicly and to denounce every form of injustice. In her eyes, silence in the face of injustice is a sin, even if one is a peasant or a woman.”[1]

Sources

Grumbach, Argula von: Schriften. Bearbeitet und herausgegeben von Peter Matheson. Heildeberg 2010.

Matheson, Peter: Argula von Grumbach. Eine Biographie. Göttingen 2014.

Matheson, Peter: Argula von Grumbach und die Anfänge der Reformation. In: Greiter, Susanne/Zengerle, Christine (Hg.): Ingolstadt in Bewegung. Grenzgänge am Beginn der Reformation. Göttingen 2015, p. 17 – 34.

[1] Matheson 2015, p. 28.