Coco de Mer – A Nut in the Museum’s Collection

Wolfgang Cortjaens | 18 October 2023

A glance at the collections of the Deutsches Historisches Museum reveals the immense variety of objects that are related to different epochs and topics of German history. They tell stories of our past or current lives, of famous or often unknown persons and events. In our new blog series #Umweltsammeln (#Environmentcollecting) we present various objects that have to do with the topic of “environment”. Unexpected questions raised by the heads of the different collection sections open new perspectives on historical objects and often reveal startling parallels to questions that deal with our current world.

Dr Wolfgang Cortjaens, head of the Applied Arts collection, highlights the change in perspectives on a curious, intriguing object in the collection: The sea coconut, or Coco de mer, was and still is not only a coveted trading commodity, but has taken on many different meanings over time. As a museum object it opens several different perspectives on a natural product and its historical contextualisation.

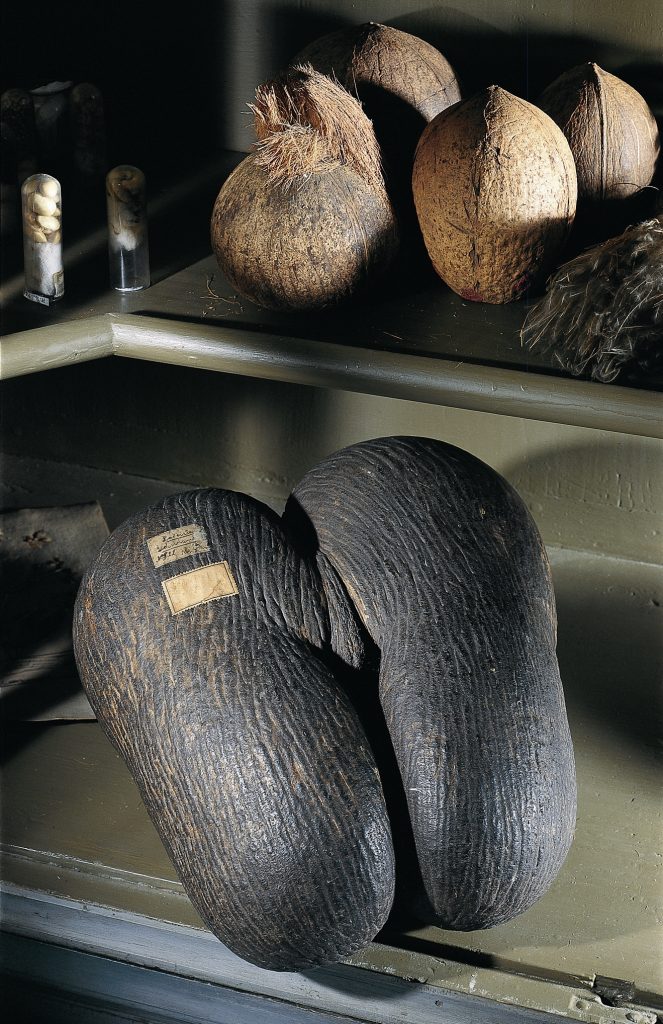

In the Applied Arts collection there is a seedcase of considerable size that has been sawed in half along the seam, emptied, and glued back together again.

Sea coconut (Coco de mer), Berlin, Deutsches Historisches Museum / Photo: Sebastian Ahlers

In the gap between the two halves is a bushel of fibres resembling a coconut husk. This at first glance perhaps slightly disconcerting object is a so-called sea coconut, or Coco de mer. More precisely, it is the bilobed housing of the fruit of a Seychelle palm tree with the botanical name Lodoicea maldivica. It can sometimes reach a size of up to 50 cm in diameter and is the largest coconut in the world. It grows only on the islands Praslin, Curieuse and Silhouette of the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean. The first written mention of the plant came from the Italian explorer Antonio Pigafetta (ca. 1480–1534), the chronicler of the first circumnavigation of the earth by the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan, in 1519-1522. Pigafetta reported on floating nuts from huge trees that were apparently growing on the bottom of the sea.[i] In fact, the specimens that he and other voyagers later observed had been washed away from their native land and drifted in the currents to the faraway coasts of India, Sri Lanka, South Africa and the Maldives. In 1563, the Portuguese medic Garcia de Orta was the first to assign a botanical name to the plant, which he called Coco das Maldivas, but it wasn’t until the 18th century that the actual place of origin of the fruit became known, which only added to its myth.

From the beginning of trade in the Indies the Coco de mer was a highly coveted and costly commodity. Its unusual size and the erotic associations engendered by the form of the seedcase – the two halves call to mind, depending on growth, viewpoint, and not least the mindset of the observer, male testicles, a vulva, or a shapely derrière – soon earned it the reputation of an aphrodisiac, and it was also believed to cure various ailments. In early modern Europe the sea coconut was a popular addition to princely art and natural science cabinets. These displays, which were normally limited to an exclusive circle of illustrious guests, were the result of a passion for collecting native or exotic plants, seeds, roots and fossils and compiling metals, gemstones and artistically decorated artefacts made of precious and rare materials, combined with an interest in depictions of the world as it was then known. All of the objects were subject to a idealistic principle of order which aspired to represent as comprehensive a system of the visual world as possible.[ii] This thought was carried over into the Age of Enlightenment, which adopted the form and concept of the natural history cabinet, but used it purposefully as an instrument of education and (religious) instruction. Pious contemporaries saw the cabinets as “treasure chambers of the wonders of God almighty.” [iii] The most important and only extant, in situ example of such a thematically arranged study collection is the Kunst- und Naturalienkammer der Franckeschen Stiftungen, the art and natural science cabinet in Halle, Germany.

View of the cabinet of curiosities of the Francke Foundations in the former sheep room of the orphanage, general view: Thomas Meinicke, Leipzig

Here they presented school students with models, preserved specimens, minerals and curiosa as teaching tools; the cabinet was also open to the general public. The collection continued to grow through new finds, sent, for example, by Pietist missionaries who had founded the first Protestant mission ever in the South Indian town Tharangambadi (formerly Tranquebar) within the scope of the Hallesch-Danish Mission. In 1741 the collection comprised 4,700 objects, including a good-sized Coco de mer.[iv]

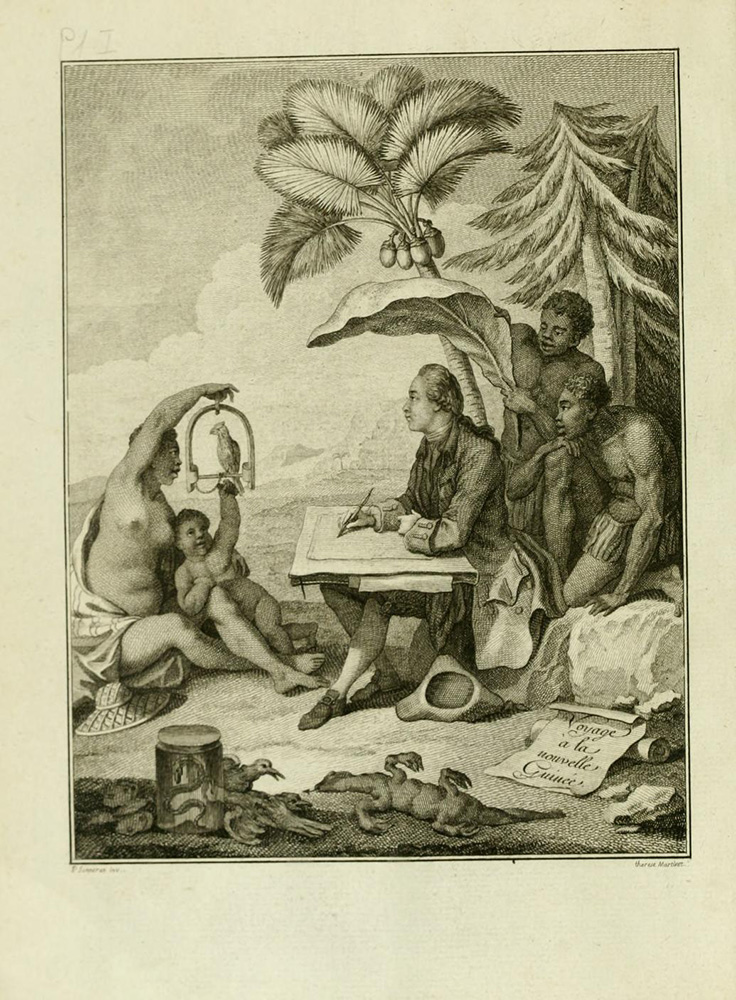

When the French seafarer Marc-Joseph Dufresne (1724–1772) discovered the true native land of the Coco de mer in the Indian Ocean in the 18th century and a few years later the botanist and explorer Pierre Sonnerat (1748–1814) devoted the first chapter of his book Voyage à la Nouvelle Guinée (1776)[v] to the fruit, a wave of exploitation set in, at the end of which the plant just barely escaped extinction. Today it is classed as one of the highly endangered plant species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). One reason for this is its slow growth: the maturation period of the tree averages 30 years. Export is therefore strictly regulated by the government of the Republic of Seychelles.

Older examples of the sea coconut can still be found in art galleries and antique shops, sometimes as splendidly boxed curios or acting as luxury goods. Usually they are decorative craft pieces stemming from the 18th to the early 20th century, e.g., hinged caskets with silver clasps. In natural science or botanical collections the fruits are often mounted on stands or equipped with fixtures for easier handling or exhibiting. A case in point is the specimen in the National Museum of World Cultures (formerly Tropenmuseum) in Amsterdam.[vi]

It has not yet been possible to determine the age and origin of the Coco de mer in the Deutsches Historisches Museum, which was purchased in 2001 at a varia auction together with other applied art objects, probably with a view to the installation of a “cabinet of art and curiosities” in the DHM’s former Permanent Exhibition. Its presentation in future exhibitions will no doubt have to be seen in the context of current debates about how to deal with natural resources and with a view to the inherent colonial implications, taking account in particular of the aspects of global history even without knowledge of the individual history of the object itself.

[i] An abridged print version of Pigafetta’s manuscript first appeared in French around 1525. [https://archive.org/details/levoyageetnauiga00piga, 2023-09-25]. The Italian translation from 1536 was first printed in Volume One of Giovan Battista Ramusio’s collection of travel reports (Della navigationi et viaggi, Venice, 1550).

[ii] Cf. Horst Bredekamp, Antikensehnsucht und Maschinenglauben, Die Geschichte der Wunderkammer und die Zukunft der Kunstgeschichte, (Kleine Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek, 41), Berlin 1993. For an overview cf. Gabriele Beßler, Kunst- und Wunderkammern, in: Europäische Geschichte Online (EGO), ed. by Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte (IEG), Mainz 2015-07-09. URL: http://www.ieg-ego.eu/besslerg-2015-de URN: urn:nbn:de:0159-2015070810 [2023-09-25].

[iii] Johann David Köhler, Anleitung für reisende Gelehrte, Bibliothecken, Münz-Cabinette, Antiquitäten-Zimmer, Bilder-Säle, Naturalien- und Kunst-Cammern u.d.m. mit Nutzen zu besehen, Frankfurt/Leipzig 1762, p. 216 https://germanhistory-intersections.org/de/wissen-und-bildung/ghis:document-138 [2023-09-25].

[iv] Responsible for the conception of the cabinet of curiosities was the universal scholar, painter and copper engraver Gottfried August Gründler (1710–1775), who also penned the handwritten catalogue of the Art and Natural Science Cabinet in Halle (1741). Cf. Thomas Müller-Bahlke, Die Wunderkammer: Die Kunst- und Naturalienkammer der Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle (Saale), Halle: Verlag der Franckeschen Stiftungen, 1998.

[v] Cf. Pierre Sonnerat, Voyage à la Nouvelle Guinée, dans lequel on trouve la description des lieux, des observations physiques & morales, & des détails relatifs à l’histoire naturelle dans le regne animal & le regne végétal. Enrichi de cent vingt figures en taille douce, Paris 1776. Only a year later the first German translation appeared in Leipzig: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb10469721?page=7 [2023-09-25].

[vi] Afrikaans, before 1927, Inv.-Nr. TM-400-189. Permalink: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/126960

|

|

Dr. Wolfgang CortjaensWolfgang Cortjaens is head of the Collection of Applied Art and Graphics of the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |