Only on 8 May? Days of liberation in Europe

Alfons Adam | 28 May 2025

Since Richard von Weizsäcker’s famous speech in 1985, the 8th of May is primarily celebrated in Germany as the day of liberation. What was liberated, however – over a much longer period that began in 1943 and did not end on 8 May 1945 – were the European countries occupied by Germany, the first concentration and extermination camps, and the victims of the Nazi regime. In European cities, images of the liberation emerged which provide insight into the contradictions of the end of the war. A miniseries.

Part 2: The ends of the war by Yevgeny Khaldei

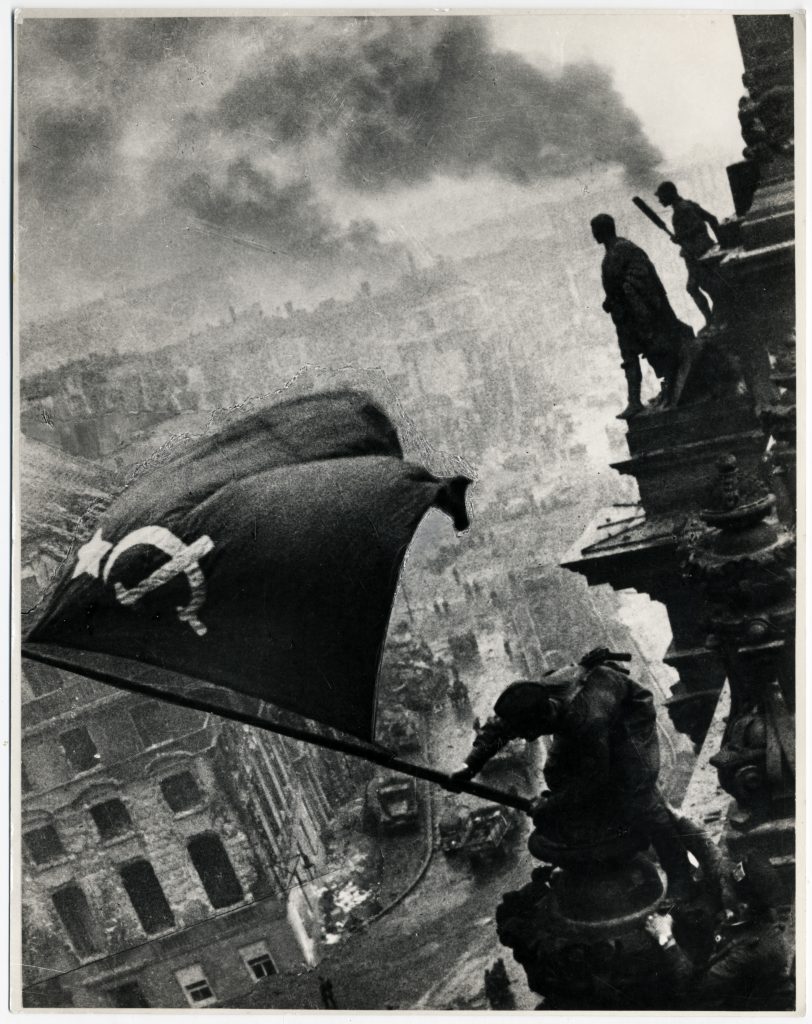

After almost six years of war that cost the lives of more than 40 million people, the majority of them civilians, the Second World War in Europe came to an end with the unconditional surrender of the German forces on 8 May 1945. The most famous photograph of the end of the war shows two Red Army soldiers raising a Soviet flag on the Reichstag above the smoking ruins of Berlin on 2 May 1945.

The pictorial icon stems from Yevgeny Khaldei (1917–1997), who had been working as a war correspondent for the Soviet news agency TASS since the German invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941. Khaldei had the scene at the Reichstag re-enacted, which had already taken place on 30 April 1945. He also retouched the photo in several places: one of the two soldiers was wearing a watch on both wrists, which would have exposed him as a plunderer. Khaldei also mounted the dramatic clouds of smoke into the background and borrowed the elegantly waving flag from another shot from his photo series.

Khaldei came from a Jewish-Ukrainian family and grew up in East Ukrainian Donetsk. His mother was murdered in a pogrom during the Russian civil war in 1918; his father and three of his sisters were shot by Germans in 1941/1942. Khaldei’s first assignment as a war photographer was in the Russian port city Murmansk, which the Red Army successfully defended in 1941. From 1942 on he photographed the fighting in southern Russia, in the Ukraine and on the Crimean Peninsula. With the Red Army, Khaldei liberated the European capitals Belgrade, Budapest, Vienna and Berlin in 1944/45. Khaldei became the chronicler of the day-after-day endings of the war in the different countries after years of German occupation.

A year before the end of the war, the Red Army freed Sevastopol. From an airplane Khaldei photographed the ruins of the most important Soviet naval base on Crimea, which had been completely destroyed in the 1941/42 battles. A few weeks earlier, Khaldei had witnessed the exhumation of Jewish mass graves in Kerch, some 300 km east of Sevastopol, where he took no photographs or was not allowed to. After the liberation of Crimea, the Soviet government deported 200,000 Crimean Tartars and members of other ethnic minorities (Bulgarians, Armenians and Greeks) to the eastern regions of the Soviet Union because of their alleged or actual collaboration with the German occupiers. They and their descendants were only able to return to Crimea after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Belgrade was the first European capital in which Khaldei photographed the liberation. On 20 October 1944, Soviet troops celebrated together with Yugoslavian partisan units the end of more than three and a half years of German occupation. The scene of brothers-in-arms between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia staged in the photograph fell apart soon thereafter. As capital of Yugoslavia, Belgrade had been heavily bombed in April 1941 by the German Luftwaffe. The country was occupied and then divided. The German Reich exploited the so-called “Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia” economically, which was under its direct control. The population sank into poverty and food became unaffordable due to rampant inflation. The Germans introduced the Nazi racial laws against Jews and Romany. Members of both groups were the preferred victims of lethal “sanctions” in retaliation for partisan attacks. The switch-over of Romania to the side of the Allies in August 1944 caused the German front to collapse in Southeast Europe. It took until May 1944 before all of Yugoslavia was liberated.

At the end of January 1945, Khaldei came upon a married couple in the eastern section of Budapest, the capital of Hungary, which had been liberated by the Red Army a few days earlier. The couple on the wintery Ráday Street, whose names are not known, were still wearing the “Yellow Star” on their clothing, like many other Jewish Holocaust survivors in the city. In this way they hoped to protect themselves against harassment, theft, rape and forced labour under the new Soviet military administration. Khaldei’s claim that the photo was made on the day of the liberation of the Budapest Ghetto and that he subsequently tore the discriminating badges off the couple’s coats satisfies our expectations but has meanwhile been disproven.[1]

Since the German occupation of Hungary in 1944, Jews were required to wear the “Yellow Star”. Only a few days later began the deportation of almost half a million Hungarian Jews to the Auschwitz extermination camp. When the Red Army reached the suburbs of Budapest at the beginning of November 1944, the Nazi terror continued. The Germans forced tens of thousands of Jewish citizens of Budapest to build the “Southeast Wall” at the border between Hungary and Austria. Some 3,000 who remained in the besieged city were shot dead by units of the Hungarian “Arrow Cross” movement and their corpses dumped into the Danube.

At first Khaldei, who lived in Moscow after the war, was largely forgotten. But after the collapse of the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1990s, the world discovered Khaldei’s works beyond the iconic photos of the Soviet flag on the Berlin Reichstag.[2] The German capitulation on 8 May 1945 left the everyday life of the people in Sevastopol, Belgrade and Budapest largely unchanged. The postwar time had begun there earlier, although it was followed by new experiences of violence precisely in the parts liberated by the Soviet Union.

[1] Peter Pastor: Misled by Evgenii Khaldei: “Budapest Ghetto”. Photos Staged outside the Ghetto and Their False Narratives, in: Holocaust and Genocide Studies 36, 1/2022, pp. 89–98.

[2] The photography collection of the Deutsches Historisches Museum contains many photographic works by Yevgeny Khaldai: https://objekt.db.dhm.de/

|

|

Alfons AdamDr Alfons Adam is research curator for Eastern Europe of the Documentation Centre “German Occupation of Europe in the Second World War” (ZWBE) at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |