On the Transformation and Usage of the German Language since the 9th Century

Matthias Miller | 8 September 2022

10 September 2022 is the Day of the German Language. Against this backdrop, Matthias Miller, director of the DHM’s library and the manuscript collection / old and valuable books, presents six selected works that bear witness to the development of the German language.

Like every year, the Verein Deutsche Sprache e.V. (German Language Association) has declared the second Saturday in September to be the Day of the German Language. More or less parallel to this, the publishing house Langenscheidt Verlag recently selected ten candidates for the Youth Word of the Year 2022, which is always a gauge of the changeability of language and its function and usage. It is interesting that two words made it onto the list that come from the field of computer games: “smash” as an expression of feeling attracted to someone, from the game “Smash or Pass?”, and “sus” for suspicious or suspect, from the game “Among Us”. The favourite words among teenagers are still strongly influenced by English-language expressions, including “slay” for someone who is very self-assured, or the no longer new “Bro” for brother or pal. That “Macher” (mover and shaker) was on the list was to be expected, but “bodenlos” (literally bottomless, but meaning unbelievable or bad) was a surprise.

The library and the manuscript collection / old and valuable prints of the Deutsches Historisches Museum are full of examples that either transmit the German language themselves or attest to its transformation and the attempts to standardise it. By means of a chronological tour from the 9th to the 20th century, I would like to present a few examples of such works, but also show that two historical components are relevant for taking objects into this collection of the Deutsches Historisches Museum: to be German and to speak German.

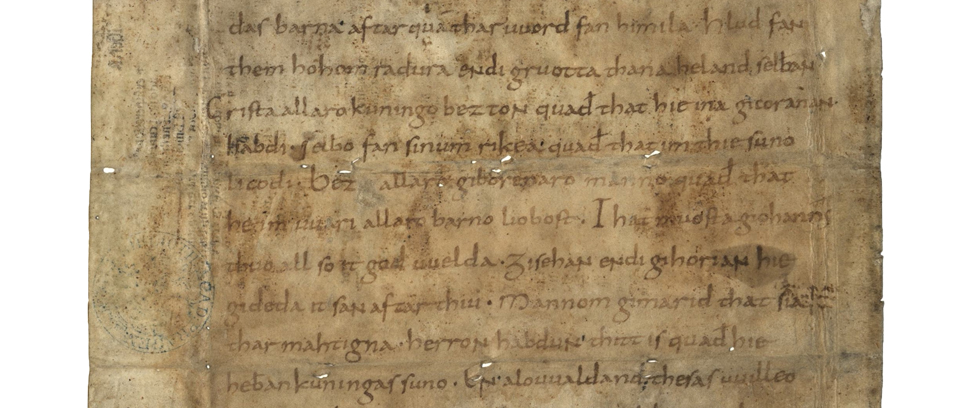

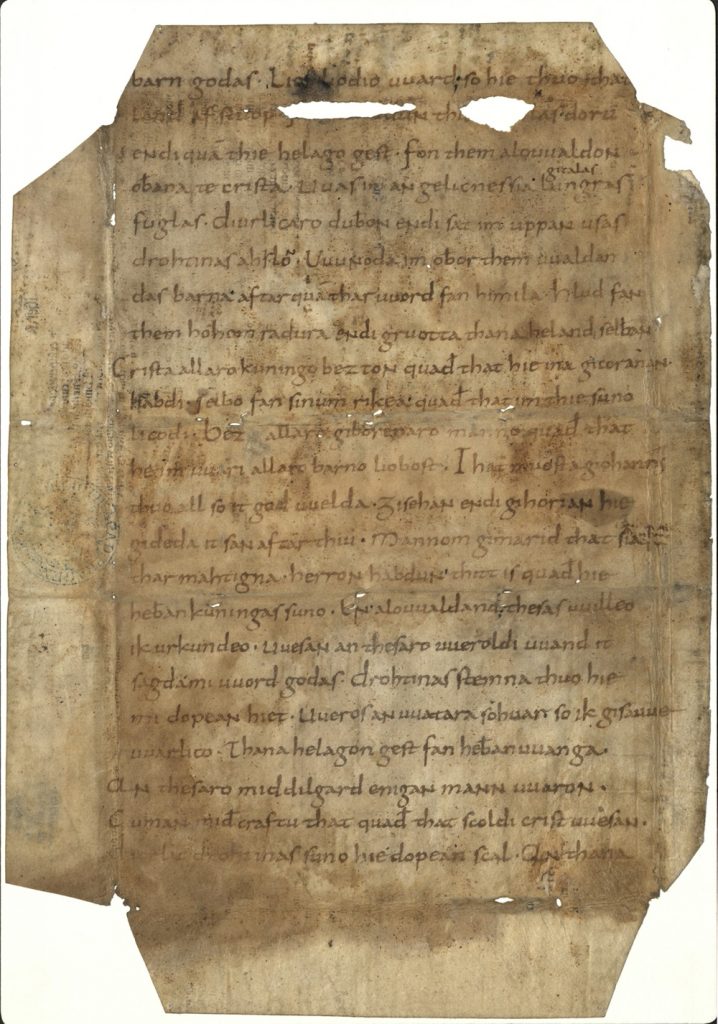

The Heliand Fragment

One of the greatest treasures of the DHM is the so-called Heliand Fragment. It is a parchment sheet on which a monk around the year 830 AD, wrote in Carolinian minuscule and in Old Saxon the biblical story of the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan by John the Baptist. It is a fragment of a manuscript of which a further sheet is preserved in the library of the University of Leipzig. In the late 16th century, the manuscript was taken apart and the individual sheets were used as book covers, which meant that wear and tear caused the outer side of the sheet to be barely legible. Old Saxon is an obsolete dialect from which only two texts have survived, the Old Saxon Genesis and the Heliand. Heliand means “Heiland” in German or “Saviour” in English, and the text brings together episodes from the biblical Gospels in a story called a Gospel harmony. In the Capitulary of the Frankfurt Council of 794, Charlemagne had proclaimed that one can pray in any language and will be heard by God if one only prays properly. After his coronation on Christmas Day in the year 800, Charlemagne introduced extensive reforms that aimed, on the one hand, to standardise the language and on the other, to establish uniform liturgical texts in the empire. The idea that it was possible to pray in the vernacular had the result that the most important liturgical texts such as the Baptismal Vow, the Apostles’ Creed and the Lord’s Prayer were translated into Old High German. The Freising Pater Noster from the beginning of the 9th century, which has survived in a manuscript now found in the Bavarian State Library in Munich (Clm 6330), is alongside other concurrent texts an impressive example of this practice: “fater unser du pist in himilum …” (“Our Father who art in Heaven”). Longer texts were also soon translated into German or originally written in German. These include the rhymed poem Heliand by an anonymous author. The Berlin fragment combines two of Charlemagne’s central reform ideas: the standardised Carolinian minuscule script and the biblical text in the vernacular. The Old Saxon text can easily be read in the minuscule, but is far more difficult to understand it. However, with some effort much of it can be translated into current High German, such as the 7th line from the top: “aftar quam thas uuord fan himila” (und das Wort kam vom Himmel / and the Word came from on high).

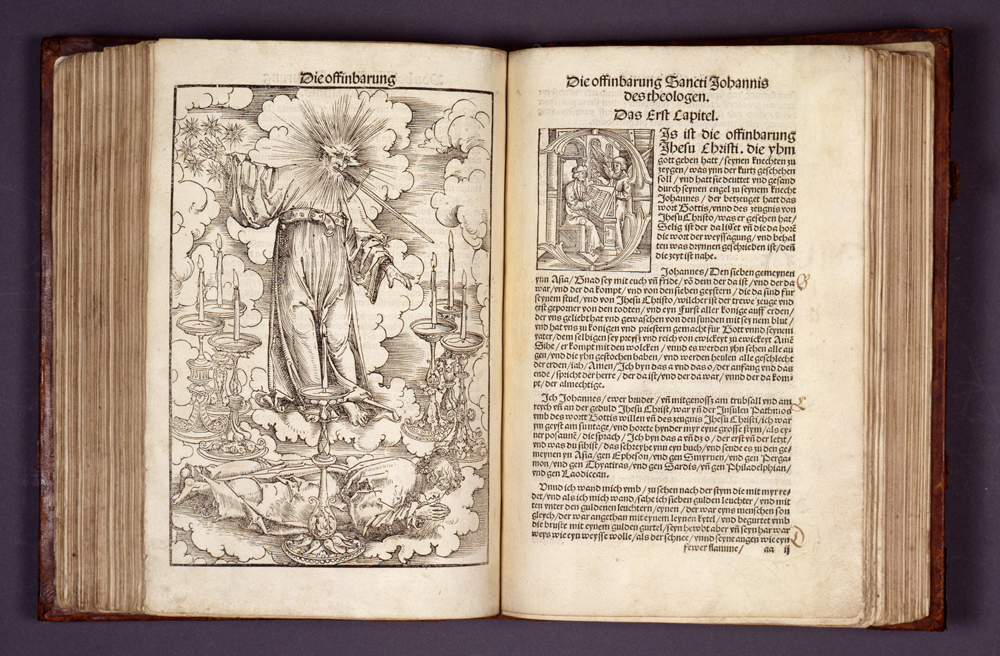

Martin Luther’s September Testament

The Day of the German Language on 10 September 2022 coincides almost exactly with the 500th anniversary of the appearance of the so-called September Testament of 21 September 1522. Luther, who since 1520 had been excommunicated by the pope and condemned as an outlaw by the emperor and had taken refuge in the Wartburg Castle above Eisenach, had translated the New Testament into German in only 73 days, using the reprint of a Greek edition published by Erasmus of Rotterdam in 1519 and the Latin Vulgate as his sources. Although Luther did not know Greek very well, he broke new ground by using the original Greek text to verify the Latin version. With his biblical prose he created a monument that left an indelible mark on the German language and, with its alliterations, still influences the rhythm with which the Bible is read: “Vnnd es waren hirtten ynn der selben gegend auff dem feld, bey den hurtten, vnnd hutteten des nachts, yhrer herde … / And there were in the same country shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night …”

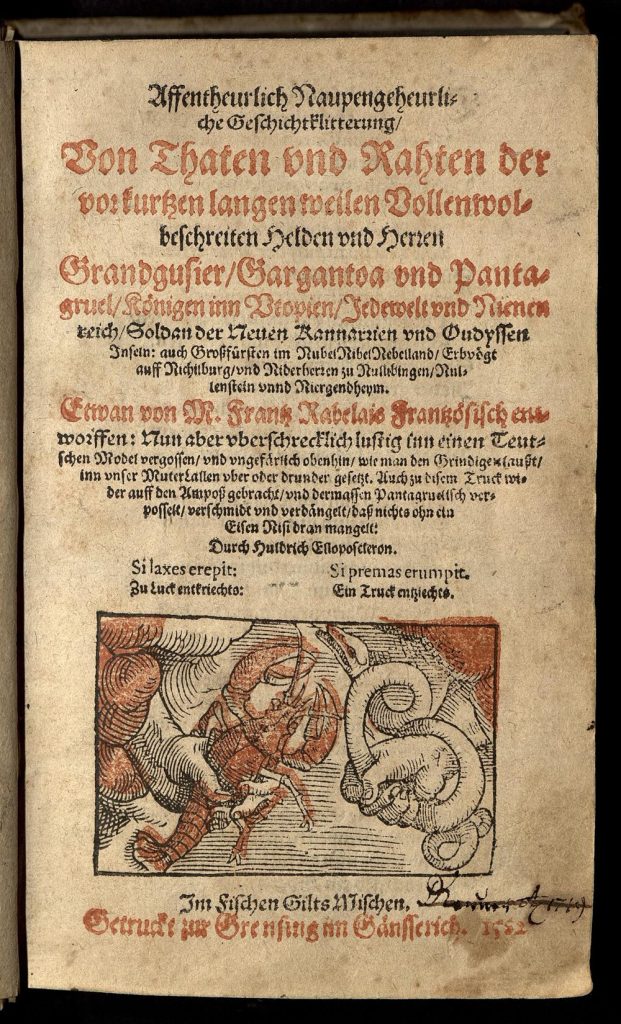

Johann Fischart and the so-called Geschichtsklitterung

The attempt to translate François Rabelais’ novel “Garantua and Pantagruel” (1533) into German culminated in a magnificent language experiment in 1575: the “Abenteuerliche und Ungeheuerliche Geschichtschrift” by the Early New High German author Johann Fischart (1546/47–1591). Never before had a translator attempted such a feat in the German language, whereby the word “Geschichtklitterung” (story conglomeration) appeared in print in this edition for the first time. Due to its experimental language, the work has sometimes been called the “Finnegans Wake” of the 16th century. The DHM copy contains the names of several German philologists who once owned the work and who evidently used it for their studies of the German language. The entries by the writer and lyricist Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter (1746–1797) and the philologist and author Carl August Böttinger (1760–1835) show that German philology of the Enlightenment and Romanticism dealt extensively with this work.

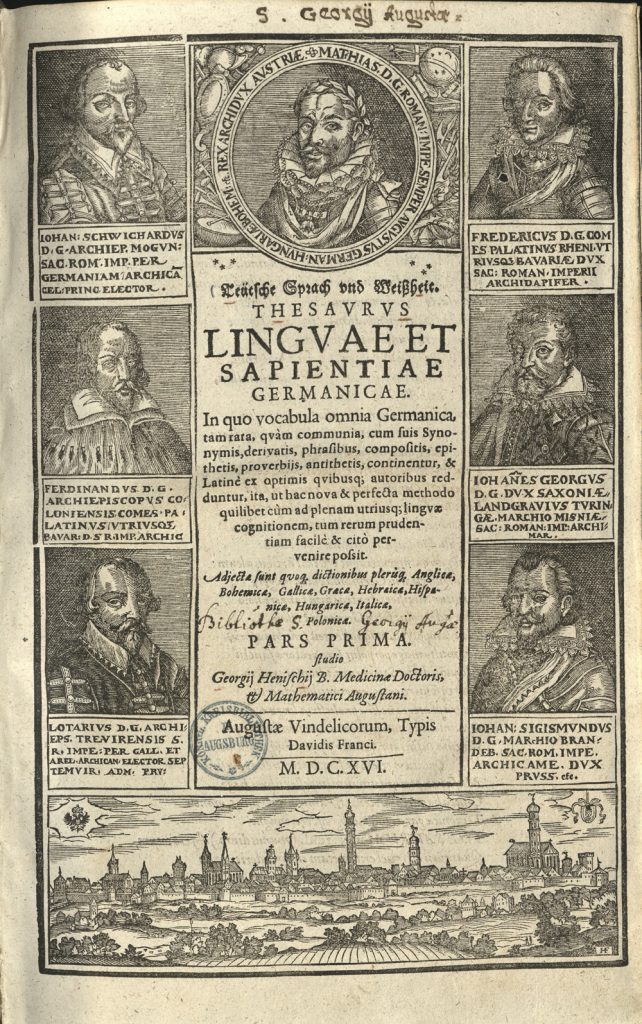

Georg Henisch and the first German dictionary

In 1616 the first volume of the first German dictionary was published in Augsburg under the title “Teütsche Sprach und Weißheit. Thesaurus Linguae Et Sapientiae Germanicae” (German Language and Wisdom), which the author Georg Henisch had compiled over several decades. The first volume treats only the letters A to G and compares the German with nine other languages (English, Bohemian, French, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Polish, Spanish, and Hungarian). Published two years before the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War, the work was unfortunately never completed. The title page shows alongside Emperor Matthias the six prince-electors, including, right next to the emperor, the elector Friedrich V of the Palatinate, who two years later was to become his bitterest enemy. The juxtaposition of the German language with the other European linguae francae shows how disparate the Holy Roman Empire was at the time, and was to remain so for the next thirty years. As the first German dictionary, this volume was of elementary importance for the consolidation of the German language and as an account of the vocabulary used at the time. In the extensive lemma “Deutsch” (German), Henisch derives the term “deutsch” from Teutates, the god of Celtic mythology, which is not entirely wrong, because Testates means “father of the people” and “deutsch” today is normally derived from the Germanic term þeuðō (folk, people) and the Old High German term thiota (belonging to the people).

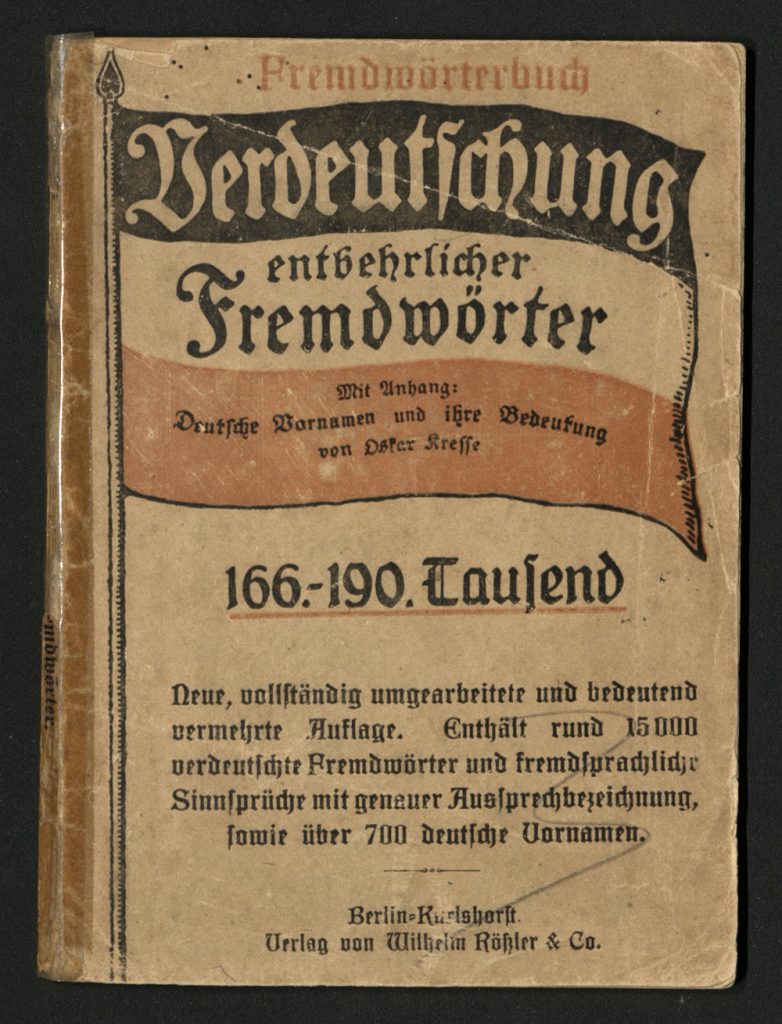

Avoid foreign terms, speak German!

Since the 17th century, due in particular to the powerful radiance of the French court in Versailles, but also the dynastic connections with France and also Russia, French was considered the “genteel” language, not only among the nobility. In the Age of Enlightenment, numerous foreign and loan words found their way into German, many of which stemmed from ancient Greek and Latin writings and quickly spread above all among the upper classes. According to the law established by the Russian linguist Raymund Piotrovsky, new language forms or words pass into a language until they have either replaced the old forms or words or have come up against the tolerance limit defined by the language community. Some forms or words disappear again, others take hold and remain. The tendency to tolerate more and more foreign words in the German language met with resistance at the latest at the end of the 19th century by a group of language researchers who wanted to promote all that was pure, true and good in the German language. This movement gained significant support during the First World War, when the Germans fought not only on the battlefields, but also for their language. Albert Tesch justified this tendency in the foreword to his book on foreign words and Germanisation “Fremdwort und Verdeutschung. Ein Wörterbuch für den täglichen Gebrauch” (Leipzig 1915) as follows: “Our people have made great sacrifices in our linguistic heritage to foreignism, and for this loss of German essence they now desire a fully valid compensation. With the outbreak of the world war, it has therefore come to a general struggle against the dreadful proliferation of foreign words.” The movement culminated in publications like the booklet by Oskar Kresse, also from 1915, about the Germanisation of superfluous foreign words and first names in Germany “Verdeutschung entbehrlicher Fremdwörter mit Anhang: Deutsche Vornamen und ihre Bedeutung”. It lists around 15,000 Germanised foreign words and epigraphs as well as more than 700 German forenames. Kresse, like his colleague Tesch, suggested replacing Aeroplan, Perron and Trottoir with Flugzeug, Bahnsteig and Bürgersteig. And that actually worked!

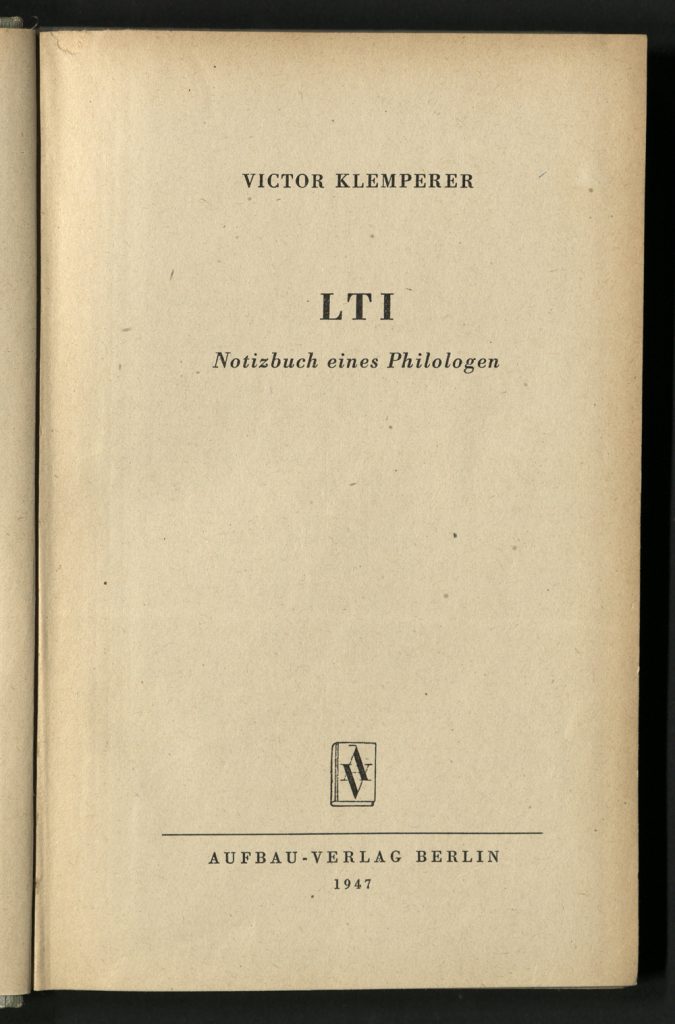

LTI – Viktor Klemperer and his analysis of the language of the National Socialists

The low inventory number 51/633 gives it away: “LTI. Notizbuch eines Philologen”, the notebook of a philologist, was one of the first books acquired and taken into the library collection of the Museum für Deutsche Geschichte, the East German history museum, which opened in January 1952. The letters LTI stand for Lingua Tertii Imperii, the language of the so-called Third Reich. The author of the book, first published in 1947, was the Romanist and German literary scholar Victor Klemperer, a Protestant convert of Jewish background who had been banned from working in his profession during the Third Reich and subjected to anti-Semitic persecution by the Nazi regime. As early as 1934, Klemperer had formulated thoughts on an analysis not only of the language of National Socialism, but also of its visual appearance, thus partly anticipating Andreas Koop’s book from 2008, “NSCI. Das visuelle Erscheinungsbild der Nationalsozialisten 1920-1945”. After the war, when Klemperer’s professional prospects were still uncertain, he continued his examination of the language of the Third Reich. The short title LTI is already an ironic play on the excessive use of abbreviations by the National Socialists: BDM, DAF, KdF, NSDAP, NSKK, SS, etc. In the first chapter, Klemperer criticises the use of “foreign expressions” in the language of the Nazis: “‘Garant’ [guarantor] sounds more important than ‘Bürge’ [bondsman] and ‘diffamieren’ [to defame] more imposing than ‘schlechtmachen’ [to speak ill]. (Perhaps not all people understand it, and that has an even greater effect on them).” (p. 15). Klemperer meticulously analyses the Lingua Tertii Imperii, dissects it, as it were, and discloses numerous linguistic stereotypes that necessarily led to a brutalisation of society. He shows this with particular effect in Hitler’s and Goebbels’ preference for sport metaphors, which often came from boxing.

Perhaps reading Klemperer’s LTI could provide an occasion, in the face of Russia’s unlawful war of aggression against Ukraine, to reconsider our own speaking patterns. How often do we stand in the frontline, go underground, take cover, or carry on turf wars with one another? Or are we having a blast, about to retrench, firing a salute, fighting our own battles, or rolling out the heavy artillery to impress someone? Language is powerful. And it does things to us.

|

© DHM/Thomas Bruns |

Matthias MillerMatthias Miller is director of the DHM’s library and the manuscript collection / old and valuable books at German Historical Museum. |