Glück auf!

Mining in German Film

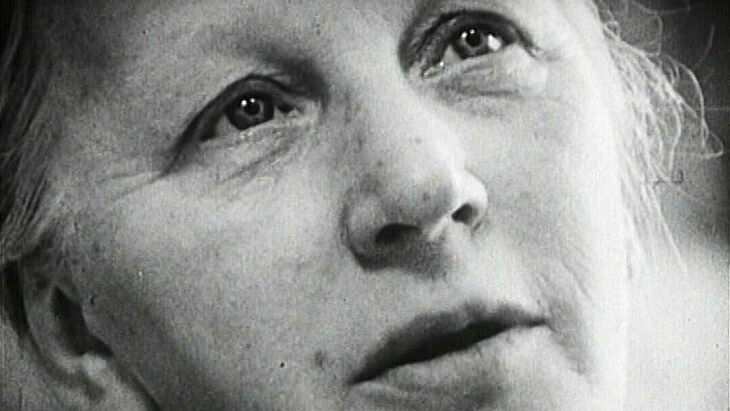

One of the earliest films ever made shows workers leaving a factory. If the medium were not so dependent on light, from a socio-historical perspective these workers could just as easily have gone down a coal shaft at the end of the 19th century. What is important for cinema are the workers, on whose side the German mining films in this series unconditionally take. With their helmets and filthy hands, the rough tone and the hidden melancholy and fear in their eyes flashing out of the darkness, the protagonists transform every gesture into a humanist revolt. But to whom do these bodies, maltreated by the state and the economy, belong, who have been subjected to the harshest conditions for decades in order to dig underground for the prosperity that never materialised for them?

The film series Glück auf! Mining in German Film shimmies along some of the highlights of German miners' film from the 1920s to the present to address issues of occupational identity and social injustice. The protagonists come from different countries and regions and belong to different genders, but are united by a "miner is miner" mentality that places solidarity above diversity. This resonates with a conflict that transcends the individual. It is the conflict between society's striving for progress and the nature destroyed by it. Nothing less than the future of our planet hangs on this conflict, which is usually depicted from a bird's eye view.

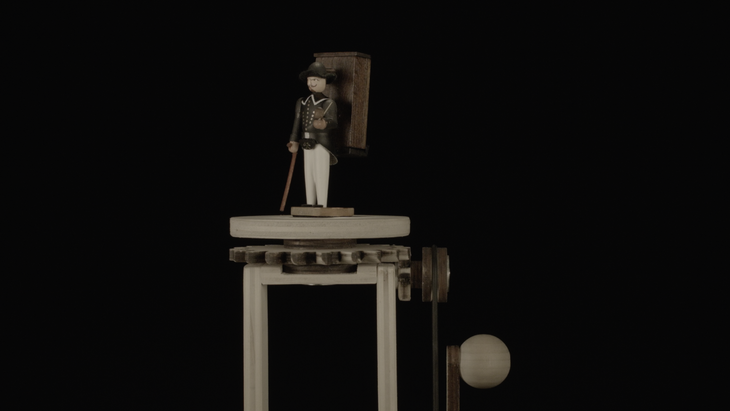

Mining has sparked political debates that have always gone far beyond the closure of individual plants or the end of certain forms of energy production. Mining has also created narratives that shape cultural memory. This can be seen, for example, in the miners' own vocabulary, in songs that have been passed down through generations, and in the long-term damage that mining has done to people and the environment. Many films therefore work with antipoles to do justice to the complexity of the conflicts associated with mining: Collective and individual, socialism and capitalism, industrialisation and nature, machine and man, calculation and catastrophe.

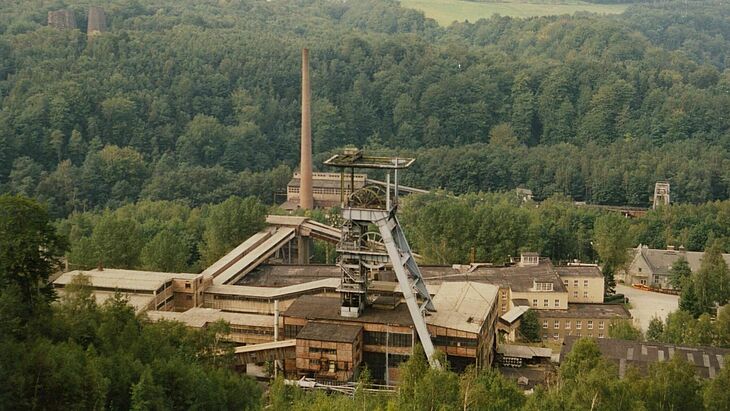

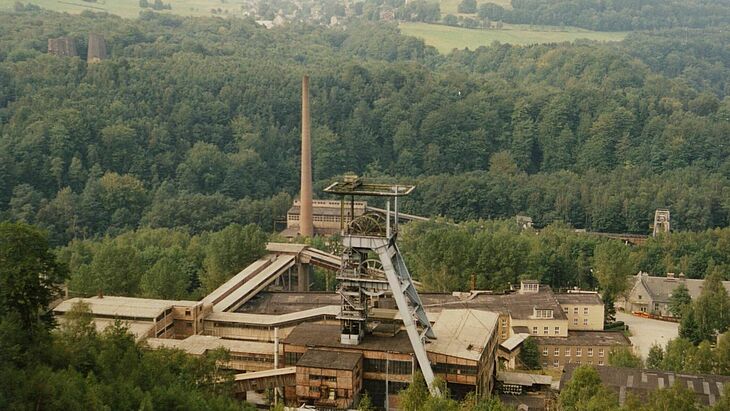

The two centres of German mining are on the edges of the country: the Erzgebirge in the east and the Ruhr in the west, ore and coal, dull promises of a future that never materialised. Two parallel lines of mining film in Germany grow out of this historical reality: the first ties the construction of the GDR closely to the productivity of the mines and understands collective labour as the necessity of a larger historical process. In the Federal Republic, a second line of development is recognisable: it focuses more on the economic conditions in which the workers have to survive. Beyond these contradictions, great similarities are revealed in the images of work and recreation, longings and mental abysses from East and West.

The sombre underlying tone is not meant to hide the fact that the films and their protagonists are constantly resisting forms of oppression and exploitation. In this sense, the film series also asks whether the Marxist and humanist lessons of the past can be transferred to the present with its only seemingly more abstract conflicts.

"Glück auf!" to all those who, with cinema, enter that darkness in which a light always flickers.

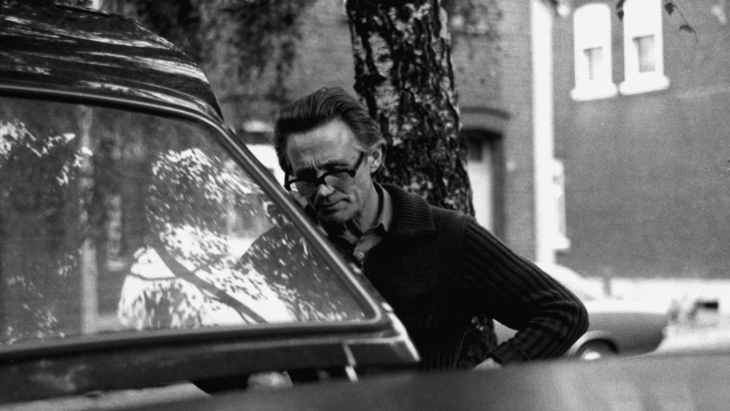

The curator of the film series is the writer and film critic Patrick Holzapfel. Among other things, he works as editor-in-chief of the blog and print magazine Jugend ohne Film, which he founded.