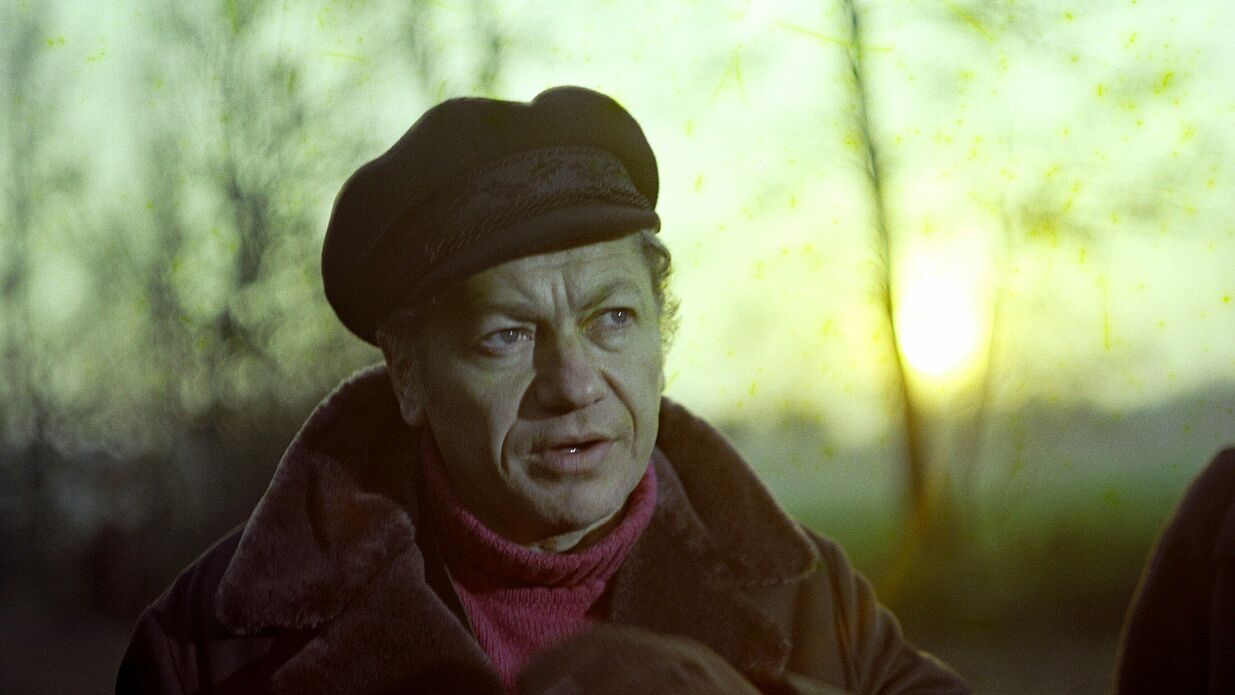

Wojciech Jerzy Has

The somnambulistic opus Sanatorium pod klepsydrą (The Hourglass Sanatorium), conceived after the student riots of March 1968, when a wave of anti-Semitic purges swept Poland, looks like a phantasmagoria between memory and evocation. Wojciech Jerzy Has was able to realize the project only after Kazimierz Kutz took over as director of the Silesia Film Studio in 1972 and pushed it through against fierce opposition from party elites. Despite festival successes in the West, the solitaire was eventually banished to the shelves of the censors. Even if Has was not directly banned from the profession, he was not allowed to make another film for nine years.

Born in Krakow in 1925, Has first made impressionist documentaries during the Stalinist era and made his feature film directorial debut in 1956 during the "Thaw" period. Although he is counted among the representatives of the Polish Film School along with Andrzej Wajda, Jerzy Kawalerowicz and Kazimierz Kutz, Has had little to do with its history-fixated mainstream. Passing time, undefined fatalism, and a sense of hopelessness characterize his early work, which is strongly influenced by Marcel Carné's existentialism and "magic realism." His inwardly broken heroes go through existential dramas, loneliness and powerlessness. In Jak być kochaną (How to Be Loved), Has used the subtle introspection of an actress hiding a resistance fighter during the war to question national mythology and legend-making. Flashback dramaturgy and the topos of farewell determine the detached tone of his literary adaptations based on models by well-known postwar authors such as Marek Hłasko, Stanisław Dygat and Kazimierz Brandys. Their basic motifs, journey and escape, prove to be illusions in the film plots; they offer no relief from the shadows of an ambivalent past.

When the New York Film Festival planned a Has retrospective in 1997, Martin Scorsese had its opus magnum Rękopis znaleziony w Saragossie (The Saragossa Manuscript) restored. "Cinema full of magic, cinema like a dream" (TIP 3/2000), from the spirit of literature and painting - located somewhere between Chirico's somnambulistic landscapes, Max Ernst's collages, Dutch still lifes, between surrealist subversion and baroque splendor. Has' aesthetic credo, "to translate into pictures what appears in literature to be unfilmable" (Kino, No. 9, 1996), also applies to his late work, produced after the enforced creative break, which, however, only rudimentarily achieves the polished elegance and ironic ambiguity of his early works. (Margarete Wach)

The exhibition Schillernder Solitär: Wojciech Jerzy Has, presented by the Zeughauskino in cooperation with the Polish Institute Berlin, is part of the festival filmPOLSKA.