Zbigniew Cybulski - The Man Who Never Arrived

Salto (PL 1965)

Zbigniew Cybulski was not a man of fast sports cars, he drove the Polish state railway. Like his fellow citizens, he used the rickety wagons that ran over the tracks that had been makeshiftly patched up after the war. And which therefore almost never arrived and departed on time. That's why you could take your time on the way to the station, because you could always jump on if necessary. Strangely enough, there are several films in which Cybulski jumps on or off moving trains. The railway was his destiny. In Salto (1965) by Tadeusz Konwicki, he hits the cross before throwing himself into the embankment next to the railway embankment, only to plunge the small town next to it into chaos. As a rejected lover, he rides the running board of Jerzy Kawalerowicz's Pociąg (1959) for a long time without ever getting closer to his bride. In Andrzej Wajda's Pokolenie (1954) he is already a supporting actor in a group of coal thieves who hijack a freight wagon. In the end, even the beating of the cross did not help him. On 8 January 1967, a good 55 years ago, a film crew waited in vain in Warsaw for its leading actor. The rest is history, Zbigniew Cybulski died in an accident.

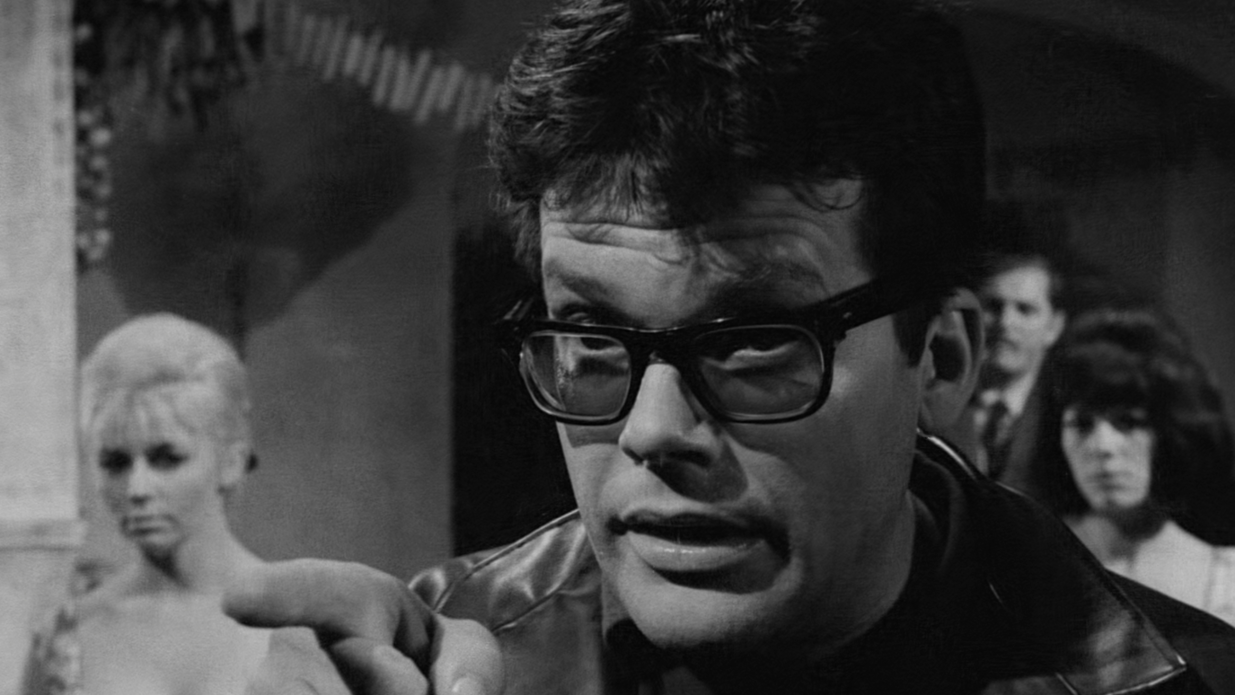

Zbigniew Cybulski appeared in 46 films between 1954 and 1967. The current retrospective presents ten selected examples, plus two posthumous works. Both his famous works have been taken into account, as well as some marginal productions that at first glance might not necessarily fit into the pantheon of cinematography. But it is precisely in these curiosities that the range of his play becomes apparent. Perhaps, after all, he took on these roles not only to try his hand at all kinds of genres, but also to escape the overpowering cliché formed by his portrayal of Maciek in Wajda's Popiół i diament (1958). In the key film Salto, he once again flaunts his typical outfit: tinted glasses, black leather jacket, sturdy shoes. But something has changed. By now, this uniform seems like a parody of Maciek, an empty shell that slinks around the figure of the ominous Mr. Kowalski-Malinowski, hiding the vacuum lurking behind it.

Cybulski's entertainment films can also be seen as attempts at liberation. In Zbrodniarz i panna (1963) he plays a captain in the criminal investigation department, in Giuseppe w Warszawie (1964) a slightly goofy painter and in Cała naprzód (1966) a swaggering merchant navy sailor. These performances are as bizarre as the films themselves, but no less worth seeing. For they not only reveal unknown sides of the otherwise cool star, they also open up surprising views of Polish cultural and social history. When, in the love drama Ósmy dzień tygodnia (1958), locked away for 25 years, landscapes of ruins stand right next to glittering department stores' worlds and the two lovers simply cannot find a place for love, this tells quite directly of the contradictions of Polish post-war history. And this happens more sensually than long historical treatises can. Thus, the retrospective Zbigniew Cybulski, the Man Who Never Arrived invites us to rediscover a legendary actor. Cybulski, who was called "Zbyszek" by his friends, was a child of the "tragic generation" shaped by war, occupation and totalitarianism, and the films are mostly about that: "Everything Zbigniew Cybulski played also told about himself." (Kazimierz Kutz)