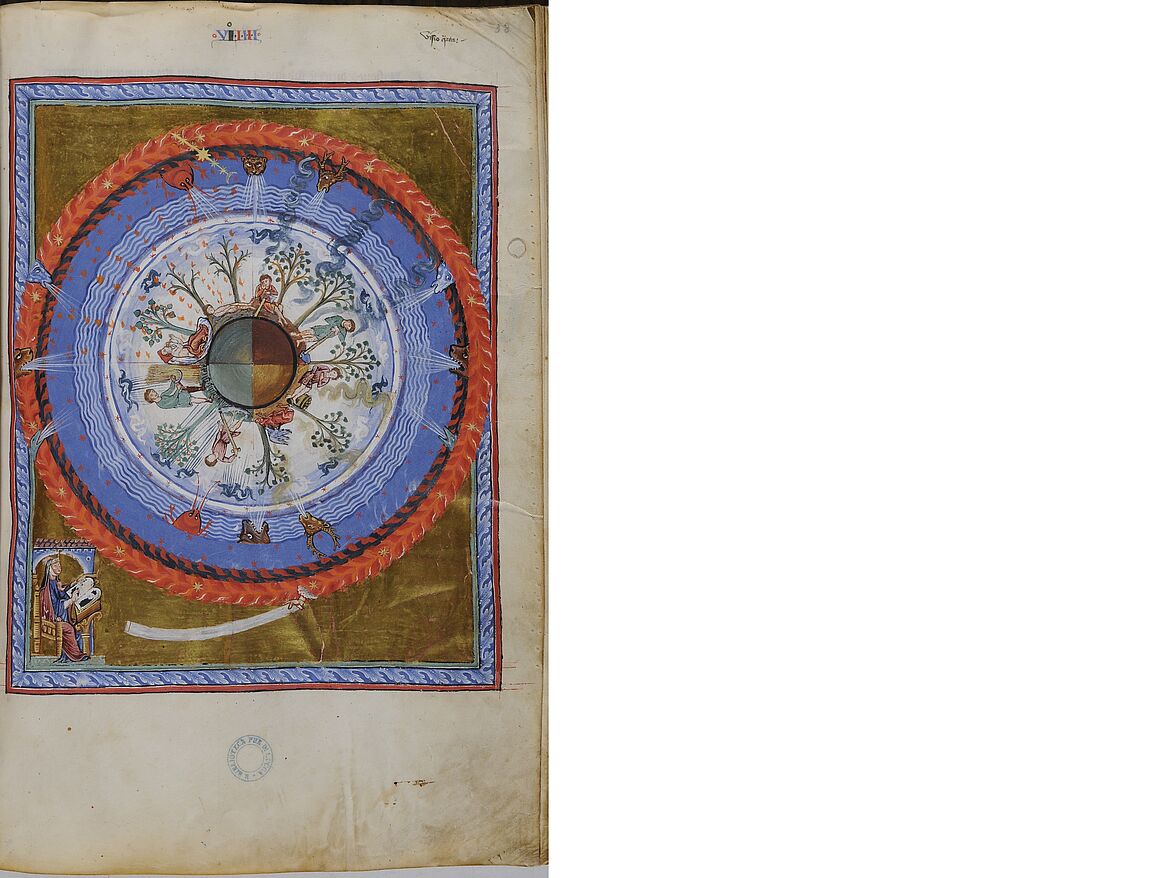

Nature is a radiant, politically charged concept. But what does it mean? How has this understanding changed in the context of faith, biology and power? The exhibition focuses on the question of how and why ideas about nature have changed. It covers examples from 800 years of German history, stretching from the writings of Abbess Hildegard of Bingen in the 12th century to the emergence of environmental policy in the 1970s.

Miniature on the blooming and wilting “greening power” from “Liber divinorum operum” by Hildegard of Bingen, fourth vision, Rhine scriptorium, 2nd or 3rd decade of the 13th century

© Biblioteca Statale di Lucca