Facing Nazi Crimes: European Perspectives after 1945

European Event Series on the exhibition “On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945–1948” to be resumed on 4 September

24 May to 23 November 2025

European Event Series on the exhibition “On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945–1948” to be resumed on 4 September

In cooperation with the Documentation Centre “German Occupation of Europe in the Second World War”

Od 24. května 2025 v Německém historickém muzeum. Ve spolupráci s Dokumentačním centrem „Druhá světová válka a německá okupace v Evropě“

Od 24 maja 2025 roku w Niemieckim Muzeum Historycznym (Deutsches Historisches Museum) w Berlinie. We współpracy z Centrum Dokumentacji „Druga wojna światowa i…

À partir du 24 mai 2025 au Musée d’histoire allemande. En coopération avec le Centre de documentation « Seconde Guerre mondiale et occupation allemande en…

“On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945–1948”

From 24 May 2025 in the Deutsches Historisches Museum In cooperation with the Documentation Centre “German Occupation of Europe in the Second World War”

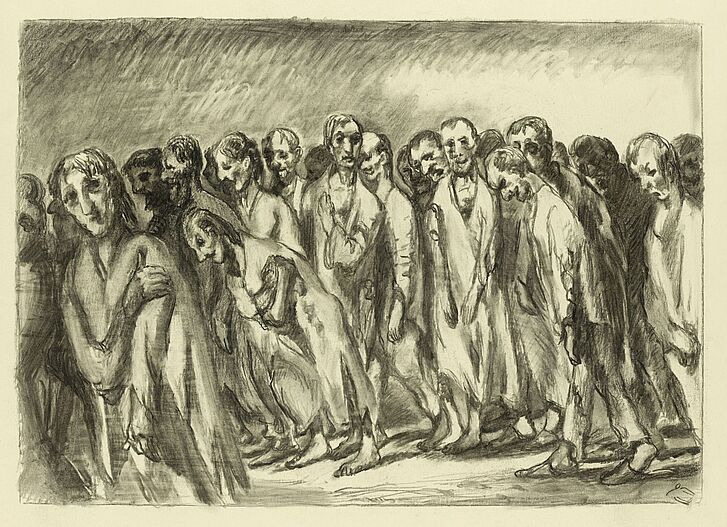

Ludwig Meidner, Trek of People, from the cycle Massacres in Poland, 1942-45, charcoal drawing, Jewish Museum Frankfurt © Ludwig Meidner-Archiv, Jewish Museum of the city of Frankfurt, photo: Herbert Fischer

The German-Jewish artist Ludwig Meidner, who lived as an emigrant in England, based his depiction of the Holocaust on reports and on his own personal imagination. It was his visit to “The Horror Camps” that showed him the true character of the genocide.

Visitors at the entrance of the exhibition “Crimes hitlériens” (Hitlerian Crimes) in the Grand Palais, Paris, 1945 © Service historique de la Défense

In June 1945, only a month after the war ended, National Socialist symbols could again be seen in Paris. In front of the Grand Palais, where the exhibition “Crimes hitlérien” took place, and on posters throughout the city, swastikas and SS symbols were depicted. They no longer stood for the rule of the German occupiers, but for their crimes, which were displayed in the exhibition.

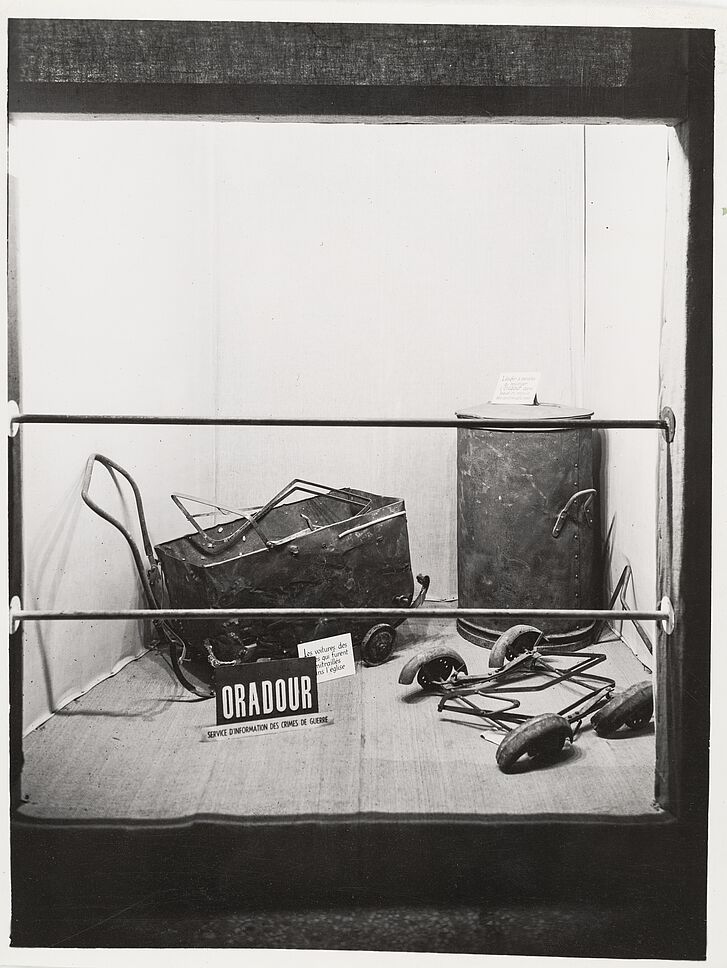

Objects from victims of the Oradour-sur-Glane massacre in the exhibition “Crimes hitlériens”, Grand Palais, Paris, 1945 © Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, Centre des Archives diplomatiques, La Courneuve

Numerous objects that were found in the ruins of the decimated village of Oradour-sur-Glane after the SS massacre were displayed in the showcases of the exhibition “Crimes hitlériens”, including a baby carriage riddled with bullets and a kitchen steamer in which a person had been murdered. Oradour-sur-Glane became a key national memorial site in France.

Pocket watch of a victim of the Oradour-sur-Glane Massacre, Association Nationale des Familles des Martyrs d’Oradour-sur-Glane © Association Nationale des Familles des Martyrs d’Oradour-sur-Glane, photo: Benoît Sadry

The exhibition “Crimes hitlériens” displayed personal belongings such as pocket watches – similar to the one shown here –, razors, toys, etc., that were found in the ruins of the village of Oradour-sur-Glane, which had been decimated during the SS massacre. Oradour-sur-Glane became a central national memorial site in France.

Museum director Stanisław Lorentz (4th from right) accompanies General Dwight D. Eisenhower (3rd from right), supreme commander of the US occupation troops in Germany, through the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża” (Warsaw Accuses), Warsaw, 21 Sep. 1945

© Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie ___ The new Polish government, now backed by the Soviet Union, saw “Warszawa oskarża” as a means to raise international awareness of the German war crimes. Museum director Stanisław Lorentz accompanied both American and Soviet delegations through the exhibition. Such visits were remarkable in the light of the increasingly aggressive geopolitical division between West and East.

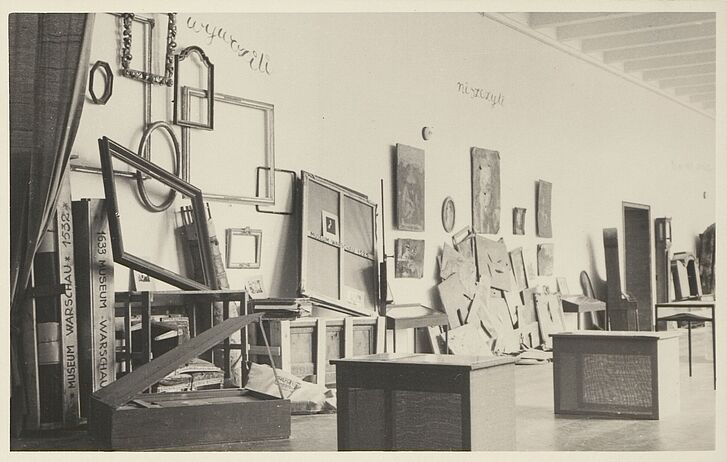

Artworks in the National Museum in Warsaw that were damaged during the German occupation, 1945 © Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie

Photographs from the years 1939 to 1945 show the destruction of the museum, which was later staged in the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża”. Throughout the entire period of occupation, the Germans had stolen works from the museum collections and taken them to the German Reich. Many objects had also been damaged during the war. In order to save the remaining works, museum staff members had to track them down in the chaos of the destruction.

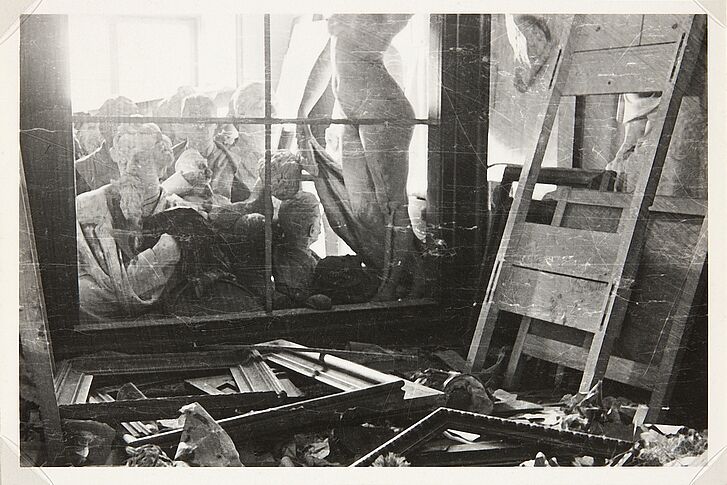

View of the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża” (Warsaw Accuses), Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie (National Museum in Warsaw), 1945, photo: Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie

Anti-German inscriptions and pictures hung on the walls of the “Room of Destructions” in the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża”. Below them were damaged artworks and objects stacked in a surrealistic disarray that recalled the destruction of the Polish museum collections during the occupation. The Germans had stolen countless works. As a reminder of the plundering, the exhibition showed wooden cases with which the booty was spirited out of the country.

Henryk Kuna, Three Marys, 1934, bronze, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie (National Museum in Warsaw), Warsaw © Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie

The sculpture “Three Marys” was displayed in the “Documentation Room” of the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża”, which according to the list of objects was the first acquisition of the museum after the war. The depiction of the biblical scene of mourning and hope of resurrection symbolised the situation of the museum at the time.

Fragment of the Adam Mickiewicza Monument made by Cyprian Godebski in 1898, bronze, Muzeum Literatury im. Adama Mickiewicza (Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature), Warsaw © Muzeum Literatury im. Adama Mickiewicza, photo: Maciek Bociański

The monument honouring Adam Mickiewicz, which had been inaugurated in 1898, stood in the city centre of Warsaw until it was destroyed by the Germans. The poet of Romanticism was considered Poland’s most important man of letters. German soldiers demolished the monument after crushing the Warsaw Uprising in 1944, but the head survived the war in the rubble of the city. In the “Room of the Warsaw Reconstruction Office ” in the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża” the head as well as related objects were presented alongside plans for the reconstruction of Warsaw.

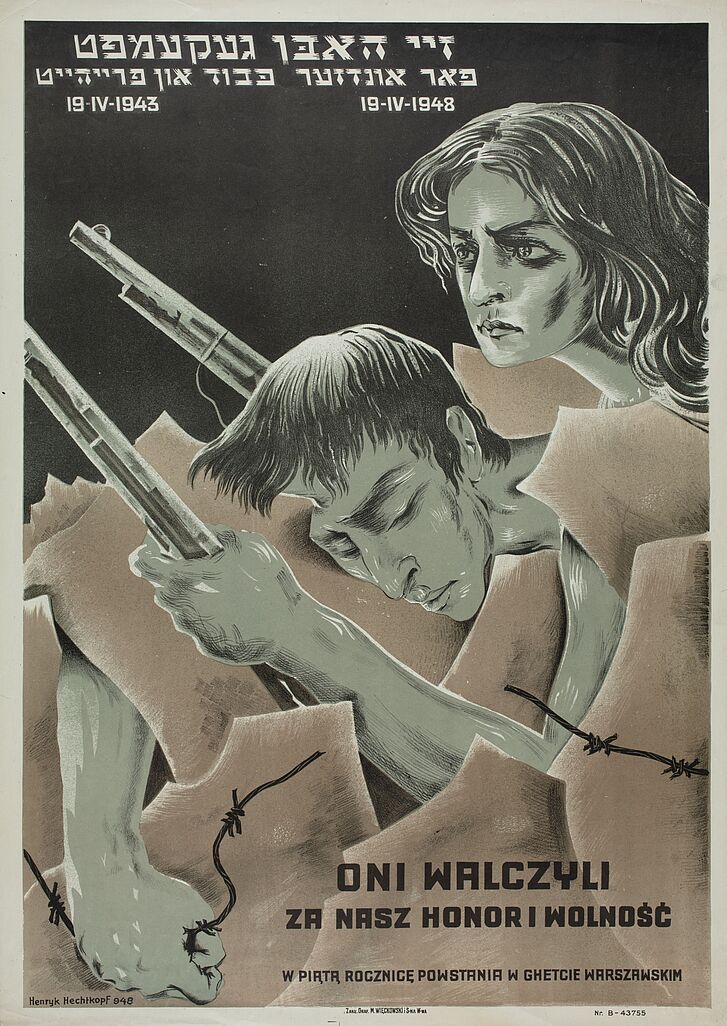

Henryk Hechtkopf, Poster on the 5th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, 1948, Stowarzyszenie Żydowski Instytut Historyczny w Polsce (Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland), Warsaw

(on permanent loan from Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute) © Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland ___ The exhibition “Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka” opened on the fifth anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. For the celebration the Central Committee of Jews in Poland tendered a poster competition. The winning poster was designed by Henryk Hechtkopf. It showed two Jewish insurgents. The text in Yiddish and Polish reads: “They fought for our honour and freedom”.

Kilim from the Łódź Ghetto, 1942, Stowarzyszenie Żydowski Instytut Historyczny w Polsce (Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland), Warsaw (Permanent loan from Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute)

© Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland ___ The kilim (carpet), which was made in the Łódź Ghetto, depicts Jewish forced labourers who are sorting out plunder taken from murder victims in the extermination camps. The kilim was meant to demonstrate the productivity of the ghetto to the German functionaries. At first, it appeared as if the ghetto inhabitants could temporarily avoid deportation to the extermination camps if assigned to forced labour. The Yiddish title “Ghetto Happiness” is an ironic reference to their situation and took up a theme from prewar Jewish literature.

Visitors in front of a showcase in the exhibition “Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka” (Martyrology and Struggle), Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (Museum of the Jewish Historical Institute), Warsaw, 1948 © PAP/Archive

The objects in the showcase within the exhibition “Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka” stood for the irreplaceable loss of the cultural and religious heritage of the Polish Jews. During the Holocaust, synagogues were destroyed and religious objects stolen. Torah scrolls were desecrated and misused by German soldiers, but also by the local Polish population, to make everyday objects.

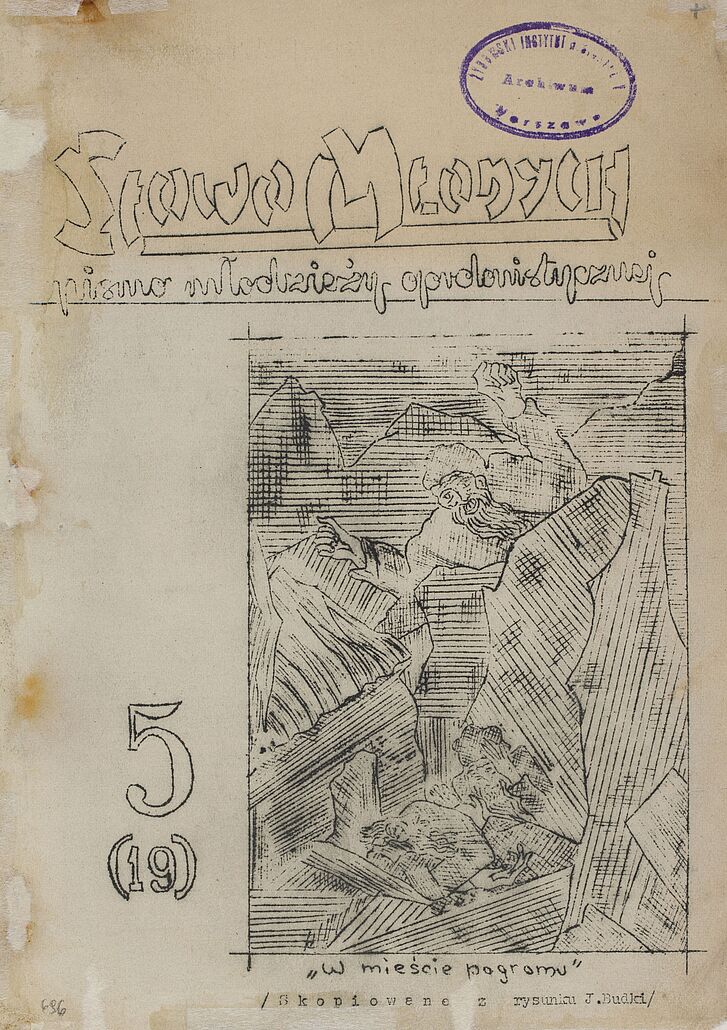

Słowo Młodych magazine, No. 5, July 1941, Stowarzyszenie Żydowski Instytut Historyczny w Polsce (Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland), Warsaw (Permanent loan from Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute)

© Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland ___ The Oyneg Shabes Archive is among the most important sources of material about the Holocaust. Part of the archive, which is listed on the memory of the World Register by UNESCO consists of Jewish underground newspapers from Warsaw. 44 underground newspapers of resistance groups of various political persuasions were preserved in the secret archive of the Warsaw Ghetto. They spread ghetto news about underground activities, the course of the war, and, from autumn 1941 on, the mass murder of Jews.

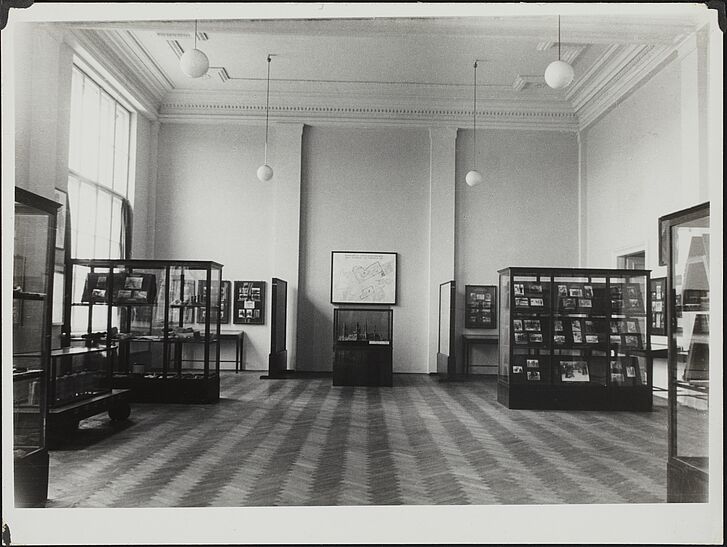

Photo of the exhibition “Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka”, Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (Jewish Historical Institute) © Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute

View of the room of the exhibition “Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka”. On the wall is a map of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, below it in the showcase a model of the bunker at 18 Miła Street.

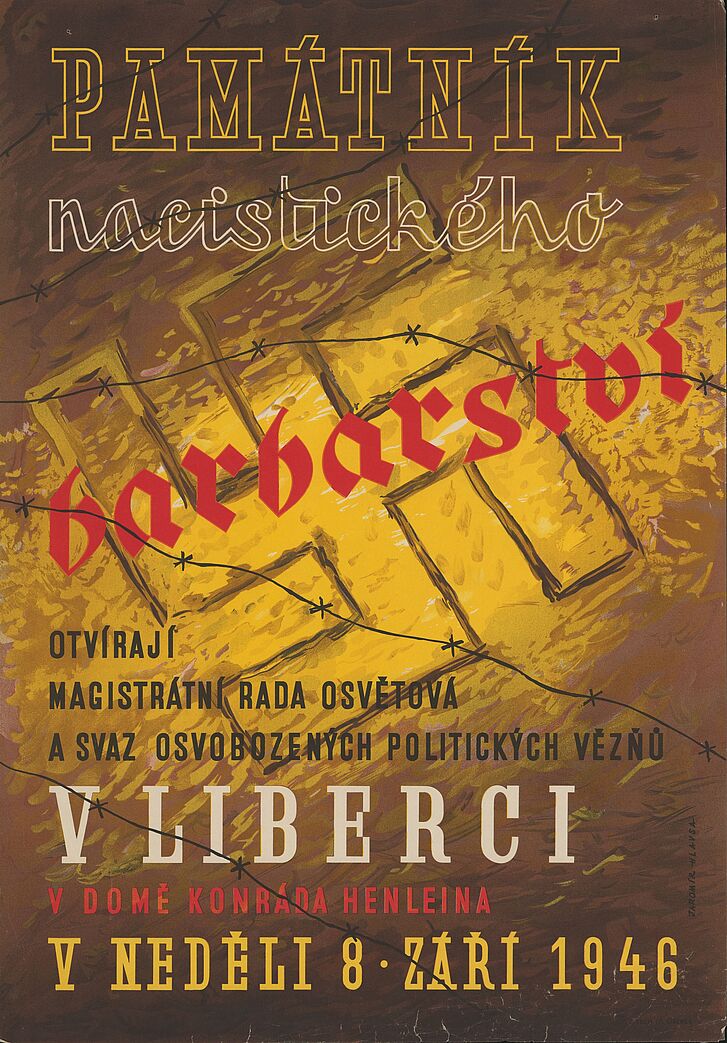

Poster on the opening of “Památník nacistického barbarství” (Memorial to Nazi Barbarism), Liberec, 1946, Moravská galerie v Brně (Moravian Gallery in Brno) © Moravian Gallery in Brno

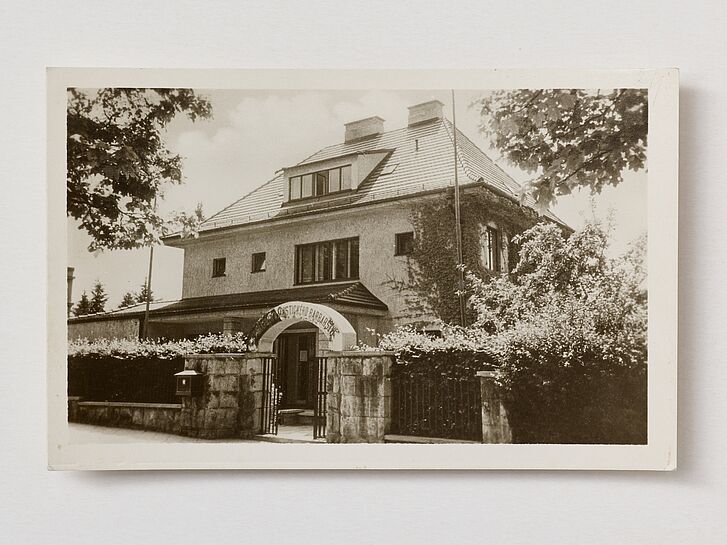

The Council of the Magistrate for Education in Liberec and the Association of Liberated Political Prisoners were listed as organisers of the exhibition “Památník nacistického barbarství” (Memorial to Nazi Barbarism). The venue was called “Konrad Henlein House” after the previous resident of the villa, the Nazi Gauleiter of the so-called Reichsgau Sudetenland.

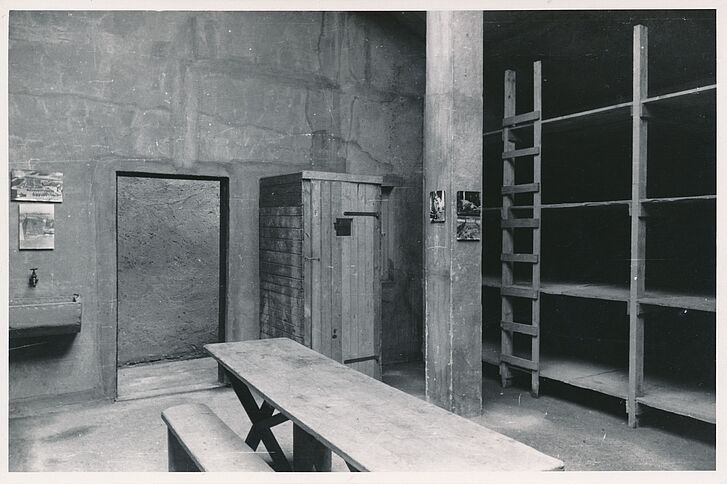

Reconstruction of a cell from the Theresienstadt Gestapo prison in “Památník nacistického barbarství” (Memorial to Nazi Barbarism), Liberec, 1946 © Státní okresní archiv Liberec

The photograph shows the reconstruction of a communal cell of the Gestapo prison in the Theresienstadt Small Fortress on the lower floor of the memorial, around 1946. In addition to the usual displays in a museum the organisers staged the sites of Nazi terror. Visitors to the memorial were to get the impression of personally witnessing the atrocities, causing a feeling of shock.

Germans visiting the exhibition “Památník nacistického barbarství” (Memorial to Nazi Barbarism), Liberec, 1946 © ČTK / Alamy Stock Photo

The preview image shown is not approved for use. For rights clearance and a high-resolution image file, please contact: anita@alamy.com ___ At the time the memorial “Památník nacistického barbarství” was inaugurated, the Czechoslovak authorities had already expelled most of the Germans from the country. Those who were waiting in Liberec for orders to leave were marked as Germans by an armband and required to view the exhibition and thus confront them with the Nazi atrocities. The photo shows Germans in the courtyard of the memorial where there was an arched gate with the inscription “Arbeit macht frei”, a reconstruction of the gate of the Theresienstadt Gestapo prison. The prison became the most important symbol of suffering under the German occupation in the Czech collective memory.

Postcard with a view of the memorial “Památník nacistického narbarství” in Liberec, ca. 1946, privately owned, Berlin, photo: Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin / Sebastian Ahlers

The memorial ”Památník nacistického narbarství” (Memorial to Nazi Barbarism) in Liberec was installed in 1946 in a villa that was originally owned by the Jewish textile entrepreneur Julius Hersch and his wife Paula. They fled in 1938 to escape the antisemitic persecution and settled in Uruguay, never returning to Czechoslovakia. Konrad Henlein, Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter of the Sudetengau, had the villa confiscated and lived there until the end of the war in May 1945.

Visitors in the exhibition “Undzer veg in der frayheyt” (Our Path to Freedom), DP Camp Bergen-Belsen, 1945 © Yad Vashem Photo Collection

On 20 July 1947, the day the exhibition “Undzer veg in der frayheyt” was opened, it was attended by around 150 delegates from the 2nd Congress of Liberated Jews in the British Zone of Germany.

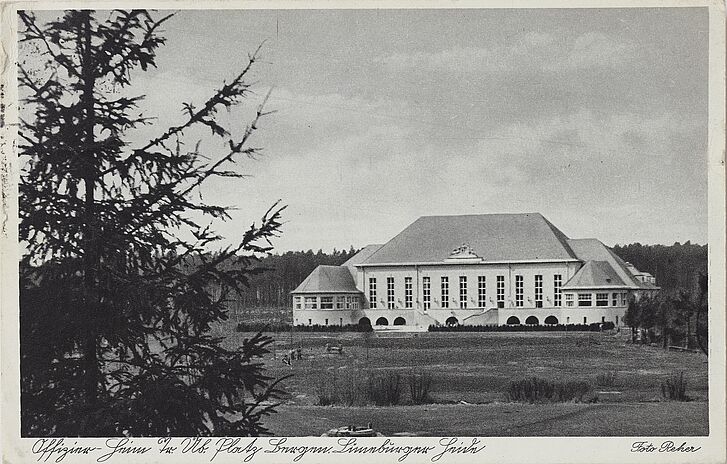

Postcard with a view of the Roundhouse, which was used in 1947 for the exhibition “Undzer veg in der frayheyt” (Our Path to Freedom), private collection, Berlin, photo: Deutsches Historisches Museum / Sebastian Ahlers

The former Wehrmacht officers’ mess was used in 1947 for the exhibition “Undzer veg in der frayheyt” by the Jewish Displaced Persons. The building was renamed “Roundhouse” by the British owing to its partially round floor plan.

Admonition at the entrance of the exhibition “Undzer veg in der frayheyt”, DP Camp Bergen-Belsen, 1947 © Massuah – International Institute for Holocaust Studies

Inscribed between trees at the entrance of the exhibition “Undzer veg in der frayheyt” was the admonition in Hebrew to remember the six million murdered Jews. For the survivors, damaged trees were a symbol of the Holocaust.

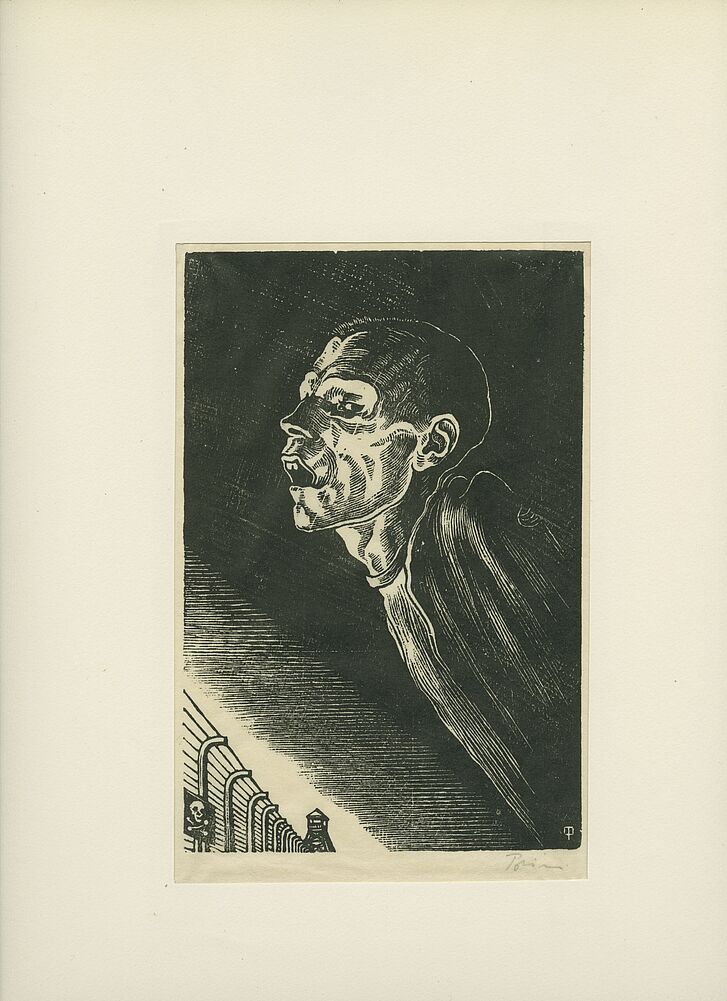

Walter Preisser, Print from a 12-part woodcut series, 1947, Mahn- und Gedenkstätte der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf (Places of remembrance and memorial Düsseldorf) © Mahn- und Gedenkstätte der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf

The Jewish artist Walter Preisser survived six years of imprisonment in various concentration camps. After the war he made twelve woodcuts that were shown in the exhibition “Undzer veg in der frayheyt”. The motifs are based on his memories of custody in the Sachsenhausen, Auschwitz-Monowitz, und Gross-Rosen concentration camps. They deal with everyday violence, torture and murder. The print shows an emaciated inmate in a camp.

Photo of the exhibition “Undzer veg in der frayheyt”, DP camp Bergen-Belsen, 1945 © Yad Vashem Photo Collection

The exhibition “Undzer veg in der frayheyt” was held in the auditorium of the main building of the former Wehrmacht barracks. By means of photographs, documents, artworks, publications, objects, and spacious installations, it created a varied image of the daily life, cultural activities, early forms of remembrance and political struggles of the DPs.

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948"

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948"

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948"

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Prologue

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "The Horror Camps"

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "The Horror Camps"

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "The Horror Camps" / "Crimes hitlériens" (Hitlerian Crimes)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Crimes hitlériens" (Hitlerian Crimes)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Crimes hitlériens" (Hitlerian Crimes)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Crimes hitlériens" (Hitlerian Crimes)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Warszawa oskarża (Warsaw Accuses)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Warszawa oskarża (Warsaw Accuses)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Warszawa oskarża (Warsaw Accuses)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Warszawa oskarża (Warsaw Accuses) / "Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka" (Martyrology and Struggle)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka" (Martyrology and Struggle)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka" (Martyrology and Struggle)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Martirologye un kamf / Martyrologia i walka" (Martyrology and Struggle)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Památník nacistického barbarství" (Memorial to Nazi Barbarism)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Památník nacistického barbarství" (Memorial to Nazi Barbarism)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Památník nacistického barbarství" (Memorial to Nazi Barbarism)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Undzer veg in der frayhayt" (Our Path to Freedom)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Undzer veg in der frayhayt" (Our Path to Freedom)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Undzer veg in der frayhayt" (Our Path to Freedom)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Exhibition Section "Undzer veg in der frayhayt" (Our Path to Freedom)

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

Exhibition view "On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945-1948" - Epilogue

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, photo: David von Becker

European Event Series on the exhibition “On Displaying Violence: First Exhibitions on the Nazi Occupation in Europe, 1945–1948” Starting on 13 May 2025 in the…

All press materials available for download are protected by copyright law. Materials may not be altered or modified in any way and are solely intended for news reporting and editorial coverage in conjunction with DHM’s current exhibitions, programmes, and projects, as well as its departments and buildings. Images must be credited to the DHM, together with the title of the exhibition and the name of the photographer.